With entrancing passion and a penchant for imagistic storytelling, Rachel Mennies depicts shifts in reality over time, drawing a detailed bridge that allows us to walk, if unsteadily, between our ancestors and ourselves. Her writing impels a search for self-knowledge that necessitates an understanding of what has come before, and she is unafraid to lay bare the privileges and problems of wrestling with one’s faith in the context of the modern world.

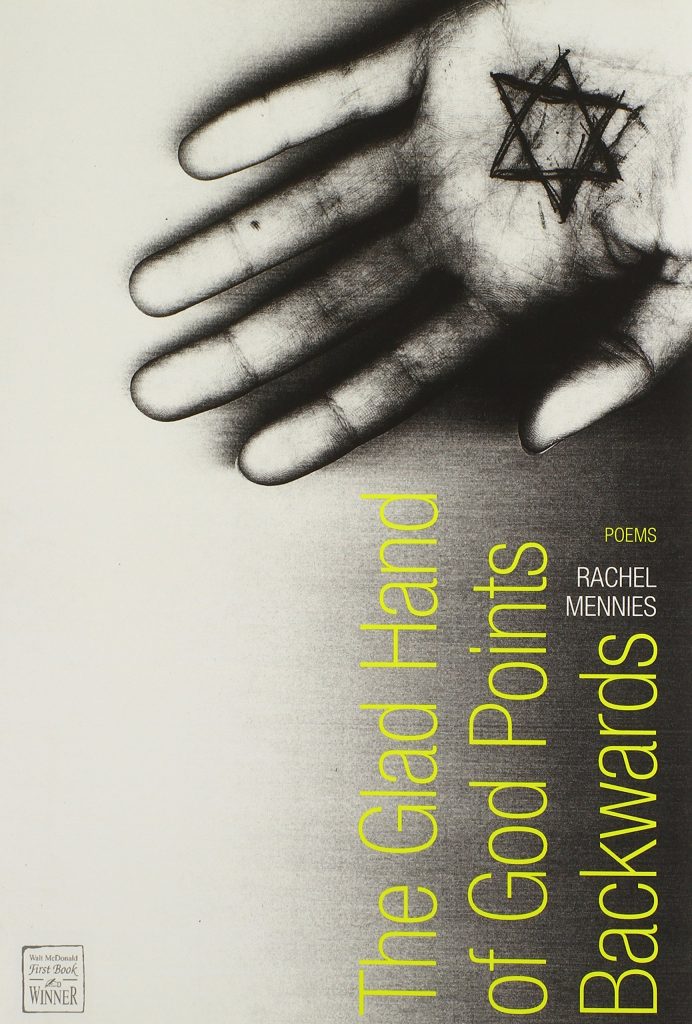

I first came to know Mennies’s work on the recommendation of a professor who saw me struggling to find a poetic voice for my own Judaism. Once I picked up The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards (Texas Tech University Press), the 2014 winner of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry and finalist for a National Jewish Book Award, I knew I’d stumbled on indispensable counsel. It was an immense pleasure, then, to get to pick her brain this past March via a two-hour, real-time Google doc, wherein I’d type questions to her and she’d type responses to me. Mennies’s work is in conversation with itself, the world at large, and inevitably you, the reader that cannot help but to engage.

Mennies is additionally the author of the chapbook No Silence in the Fields (Blue Hour Press, 2012). She took over for Robert Fink in 2016 as the series editor of the Walt McDonald First-Book Prize in Poetry, and she serves as a member of AGNI’s editorial staff.

I was hoping we might start by discussing your latest book — it was first recommended to me when I was asking around for help in learning to write about my Judaism, and I have to say I’ve been greatly guided by it. When did you first conceive of the idea for The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards?

I began that book, of all places, in a memoir workshop during graduate school. I’d never written creative nonfiction seriously before that class, and I learned quickly that the necessary “burden” of truth in memoir would make telling the family stories in The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards quite difficult. My grandmother was a young child when the Nazis rose to power in Berlin, where she lived with her parents (my great-grandparents) and her two younger sisters. They fled, in pieces, to America (we’re “chain migrants,” to use that ugly contemporary language, like so many other American families), and my grandmother was eleven when she arrived in Philadelphia.

Interviewing her for the “memoir” became quite difficult, because she kept telling the same stories different each time we talked. I realized as I spoke to her that I was actually more interested in the false starts, gaps, and twists her memory took in revisiting the dual traumas of escape and resettlement than I was in her memory’s “facts.” Poetry gave me the imaginative, less bordered space I needed to explore her story — and my own — and those early poems, which make up the first section of The Glad Hand…, are where the book began.

I feel like there are so many wonderful threads you’ve just woven in your answer and I want to pull on them all at once — but what you’ve said last seems a great place to begin. You say that the early poems began your writing of the book and enabled you, perhaps, to best begin your addressing those “gaps and twists.”

Did the book arise, ordered, in an overarching gesture, or did you find you had to play with the sections as they stand now to arrive at a greater intended truth?

Did the book arise, ordered, in an overarching gesture, or did you find you had to play with the sections as they stand now to arrive at a greater intended truth?

I love this question so much, because it allows me to reveal an aspect of my revision process that I hold truly sacred, which is: have a few great friends who know your work well and that will be honest with you about what your art needs. My early drafts of this book, which first existed as my MFA thesis, were truly chronological — they began in Germany in the 1920s and pushed through time, orderly, to the present day, where the book currently ends. I had showed this version of the book to a dear friend and gifted poet/editor, Sarah Blake, and she was the first to see that order and chronology didn’t serve the poems, because the stories in the poems were themselves collapsed and made circuitous by trauma and the multiplicity of voices held within them.

I reordered them after her observation, and this led me to its current version, with sections that exist in an order outside of time and — in the case of the third section — I really treasure that section, because it feels to me like an interrogation and discussion of the second section, which feels especially Jewish to me. The book and commentary all together in one place.

I love your saying “feels especially Jewish to me,” and not only because I feel I can relate to that, and to the cultural need for constant interrogation, but also because it brings out a certain dynamism that I feel this book tackles so well. When, in “Matriarch,” you write “had no use for sarcasm but lived thick with God’s ironies,” I felt, maybe, that you’re almost addressing this way of living as Jewish person in the world.

I suppose what I’m asking is this: do you find in writing all of your poems, of “Jewish content” or no, that you are writing Jewish poems, because of who you are?

My instinct, to answer that final question quickly, is yes, I think all of my poems are Jewish poems, and I’ll see what happens when I explore that further here. (I’ve also returned to writing more overtly about Judaism in a new project, but I’ve spent quite a bit of time away from it, and would say most of my poems don’t actually contain “Jewish content” overall.) In thinking about, as you said, “a way of living as a Jewish person in the world,” I’d see that act — in relation to my own Judaism — as being shaped and defined by feeling perpetually a step outside of or away from the living world. Perhaps that’s a feeling that comes from a history steeped in diaspora and resettling, but I think it’s also one that’s steeped in curiosity and a need, always, for questioning a thing even as we love it.

That, to me, feels especially Jewish: to hold something we love in our hands but still ask “why?” and “how?” and “who am I, to hold this?” and “how long will it stay?” I think my poems are all Jewish because they’re all curious, and they’re all petitioning, in one way or another.

I am excited to return to the book and pick your brain re: organization, sonics, and so much more, but I can’t resist asking one quick follow-up: John Hollander once spoke on Jewish poets as having a sort of double estrangement, the first as diasporic and the second as a poet, whose language is naturally estranged from prose or colloquial English (in reaction to the non-Jewish Marina Tsvetayeva’s comment that all poets are Jews) — and I heard a brief interview (or commentary?) that you did for The Lonely Hour where you mentioned making space for solitude.

I wonder if these two connect for you or if, if you wouldn’t mind, you might respond to the idea of harnessing that loneliness or solitude in service of your art?

I see an important difference between estrangement and solitude, and I find both valuable in my work, especially in relation to The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards, where I was writing about someone else’s (my grandmother’s) traumatic estrangement, then assimilation, all so that I could live this wonderfully American Jewish life where I didn’t need to know German, or Hebrew, or Yiddish (my grandmother understood, at one time, all three).

I now feel this wrenching sadness when I hear Yiddish spoken aloud, even within my own family, because its loss (as we lose more and more speakers of Yiddish) signifies, yes, a pure estrangement on both a diasporic and language level even beyond what a poet might experience, because it’s the estrangement of the immigrant from her former self for the sake of some (at that time) imaginary other: her future American family. Here is perhaps where I might take issue with the idea that all poets are Jewish, because as a Jewish poet, how could I even begin to imagine what that might mean? To separate those selves apart within me feels impossible.

I wrote directly into that estrangement in The Glad Hand…, which required deliberate solitude from me, partially because the research was traumatic and partially because, as you mentioned, I deeply struggle to make art in noise, even if that noise is internal (anxiety, distraction).

Thank you so much for indulging the above question — I find your answer highly resonant. The appreciation of culture even as it traumatizes, expressed in part in your previous answer as well vis-à-vis curiosity, is something I see coming through in The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards.

Returning to structure, when you paired “The Jewish Woman in America, 2010” that ends section one with “The Jewish Woman in America, 1941” that begins section two, and in many other moments of temporal juxtaposition (i.e. with “Huevos for Seder” and “The Memory of a Witness” back to back as section four), did the ordering simply feel right, or did you find yourself highly conscious of the exact dynamics you hoped to create?

It felt important to order “The Jewish Woman in America, 2010” before “The Jewish Woman in America, 1941” (once I saw, overall, the disservice pure chronology was doing to the book) because I wanted to show the reader the stakes of assimilation and secularism in reverse: here is this (relatively) carefree young Jewish woman choosing not to adopt some of the traditions of her religion, and then, next, behold this woman’s great-grandmother cleaning houses in West Philadelphia, unable to speak a word of English, having fled (in our family’s case) a comfortable upper-middle-class life in Berlin due to religious persecution. Choice and interpretation in how I engage with my Judaism are luxuries I’ve had that my ancestors have never had.

I am glad you mentioned “Huevos for Seder” and “The Memory of the Witness.” I agree that there’s some similar deliberate temporal play there that feels important to understanding how children and grandchildren of survivors learn about and engage with the inherited traumas of their relatives. When I lived in Spain, I learned how few active synagogues remain in so many European countries compared to here in the U.S. (it seemed to me, at least, in my experience as an American Jew — I don’t have data on this!), and I saw firsthand how many of the ones that do remain are heavily guarded. Those two poems show a speaker returning to the continent her family was forced to escape, and then imagining traveling back to the continent and the time of that exile. They show that the longing for understanding through experience, a sort of time travel, remains ultimately impossible.

I feel like what you’re saying there is so important — particularly in terms of engaging with inherited traumas. I also grew up with the opportunity to engage with a larger Jewish community and now find myself rather estranged from one. I wonder, then, how you felt about accessibility, or perhaps responsibility, in constructing your book.

Obviously, your poems offer much to any reader, but when you write about Jewish identity, do you grapple at all (even purely on the numbers) with the size of your audience, or any sense of responsibility to explain some of the rituals you invoke? With Pesach coming up I’d be remiss if I didn’t return to “Huevos for Seder” in particular.

I felt, and still feel, most responsible to the real and living people in the book: my grandmother, my sisters, and my father in particular, who appear in various versions of themselves throughout the collection. That’s the audience I was most afraid to fail, or to disappoint, because their embodied lives shape so many of the stories in those poems. I also felt the risks in writing a “Jewish book,” both toward Jewish and non-Jewish audiences, because I feel both close to and estranged from both groups simultaneously.

I didn’t feel much pressure to “get right” certain rituals — I think so many of our Jewish traditions are inflected by family, culture, place, and the very nature of diaspora. For example, since you mention Passover, there are certain ways our family approaches the rituals of that holiday that might be as Philadelphian or as international (we have Russian family, on my dad’s side, that have added some Russian “twists” to our seder table!) as it is “correctly” Jewish.

Where I did struggle, in returning to that idea of risk, is knowing that my Judaism is informed by other vectors of belief that might anger or disappoint the book’s various potential audiences. I’m married to someone outside the faith, and as some of the poems consider, this has led to some judgment of my spouse and I from both Jews and non-Jews in our extended circles.

As I left in high school the Reform, Zionist synagogue of my childhood in search of a more socially just Judaism, I have learned that such a thing as one Jewish reader does not exist.

When you mention social justice, I can’t help but think of the mission statement of AGNI, and the idea of “seeking a cultural conversation.” Even though you talk about your work, and your sense of responsibility as pertaining primarily to its subjects, there are relevant and important conversations (as perhaps you allude to in your earlier mention of immigration) that The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards participates in.

Three questions here that I probably really ought to separate: do you feel your work at AGNI allows you to engage in these broader conversations, and do you enjoy doing so? And, maybe more concretely, how do you feel about how your work might participate in a larger conversation differently over time, as the sociopolitical landscape changes? Do you believe that when you put your work out into the world, it ought to be considered in the context of the year in which it was published, or considered fluidly on the basis of what it has to say with regards to the “now,” or both?

Great questions — I’ll definitely answer these separately. Regarding AGNI, I believe in that mission, and I deeply value the work our editors do to engage and sustain that conversation. I’m doing social media for them right now, working much less on the editorial side, so I’d say this answer is much shorter: I feel I’m more like a vector for helping share that conversation than I am a direct engager with said conversation. But the work still feels important and fun.

I think the second and third questions braid together in an important way, for me. I am not sure that I, or any writer, have the luxury of imagining that my work could only speak for the time in which it was authored, or published. In the real world, that would require willful ignorance not to see how injustice itself is manifold and repetitive. There was a Twitter feed that (I believe) a historian created that tweeted out the names of each of the 937 people, mostly Jews, mostly German citizens like my family, that came to the U.S. on the St. Louis — it stated who they were and what happened to them, and where (for most of them) they were slaughtered after the U.S. government refused their entry into the country. I cannot help but remember, each time I see this Twitter feed, that the St. Louis arrived in America the same year as the Europa, the boat that held my grandmother, her sisters, and mother, and which was welcomed to New York, instead of being turned away.

I mention this feed because it was created not on Holocaust Remembrance Day, but in January of 2017, when Trump was inaugurated and just before his seven-country ban first pushed through. This tells us that there is no such thing as a book, an immigrant, or a genocide frozen in time. I hope that my work can participate in a social and political conversation in any way that helps draw attention to the plight of any person fleeing persecution hoping to seek refuge in the country that granted my family the same.

Absolutely. The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards carries weight not only for Jews today (I’m thinking, specifically, of Putin’s recent comments suggesting that Jews and other minorities may be behind the 2016 election meddling), but also for any stories of estrangement and persecution. I especially appreciate your characterization of injustice as manifold and repetitive.

With respect to engaging with the social issues of our time, I was wondering if you might share a bit on your writing process, and on what you’re writing about now (or have been during the time, as you mentioned earlier, when you were stepping away from “Jewish content”). Do you feel that with the current political turmoil, you write to confront it, or that your writing allows you to escape it, or something else entirely?

I write to confront and to escape, sometimes at once. I would push back gently on the “current” in “current political turmoil.” There’s no question that what we’re seeing in our current political moment is an explicit endorsement at the topmost reaches of our government of racism, sexism, ableism, anti-Semitism, and homophobia (and, and, and) that already existed as our American map, in so many ways.

As someone who has felt the effects of only some of these discriminations her whole life, I wish to consider this negotiation between confrontation and escape by also writing the truth about my own advantages — for example, when I talk about assimilation: my family, while Jewish, also immigrated to Philadelphia as white European immigrants. I know they experienced anti-Semitism in America, and also prejudice for being Germans at a time when America was at war with Germany, but I also know their whiteness made their assimilation ultimately easier.

I hope I can confront when others may be too tired to confront, and escape when I must escape. I see this negotiation as more connected to an external, social practice than a writing one. I do not write my poems to create social change — that is a different ongoing work I must do. I don’t feel an explicit social political urgency most of the time when I sit down to write — that is, I write very poorly when I am afraid or when I am angry — but I often write from lived experience, which embodies and encompasses both the social and the political.

I appreciate what you’re saying about fatigue, privilege, and social practice. You talk about writing about your lived-in experience — poems like “Confession,” “The Glimmering Creature,” and “Argument,” seem, to me, to bring discussions of the body, sexuality, and vulnerability to the forefront with an equal interrogative verve as was faced confronting the Holocaust narrative of The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards. I love, by the way, “the confessional poet risks only what she is willing to admit.” What questions are these more recent poems, do you feel, most concerned with? What are you working on now?

These questions, in some ways, pick up where The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards left off for me. What happened to the body of the woman in those poems? I’d been writing so much about her ancestry, her spirit, that I realized I hadn’t seen her entirely. The poems you mentioned all come from my second book, Salt (working title), which I finished last year and have been circulating to publishers. In thinking about your previous question re: the political, one thing I can never escape is my body. I must confront it, or else love it, hold it, consider it, every day. I’ve been writing into that space with these new poems, which also has led me to engage more closely with the confessional mode — itself a fraught, yet rich space for me. It connects all the way back to your very first question about how The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards began: inhabiting the territory between truth and fiction, between documentation and vision, between embodiment and sublimation, where I found myself when I couldn’t get “the facts right” about my family history. I found myself in the exact same place within my body when I began working on Salt.

So often, it seems, conflation of the speaker and author on the part of the reader is a harmful if unintentional act that can undermine the writer or the work. How do you feel defining your work as confessional affects its interaction, or your interactions, with the literary community and with your readership?

I have so many thoughts on this! I was actually just on a panel at AWP about the confessional mode and being a confessional poet, so thinking about this label has been forefront in my mind lately. (And, as you mention, poems like “Confession” write deliberately into that space.) I’d argue that the dominant mode in contemporary poetry right now explores versions of the confessional, so I think those of us writing confessional poetry in 2018 face fewer obstacles, confusions, or misrepresentations of our work than do our literary ancestors, overall.

I imagine many of my readers believe my poems are about me, and my life — and they’re right. Except when they’re not. And they never get to know the difference. That’s the Anne Sexton School of Confessional Poetry, as I understand it: “it’s true I am an autobiographical poet most of the time, or so I lead my readers to believe,” she once told a critic. This distinction feels both like artistic freedom and personal safety (as a woman writing about sex and her body, I know what the world might have to say, or might wish to do, with that work, or its author).

I love that quote — I don’t think I’ve seen it before. It reminds me, actually, of Whitman’s “do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes.” I can see how to be confessional and simultaneously not confessional — in Sexton’s words, and in yours — would be not only safer but more liberating.

To turn topics, slightly, how do you find your teaching interacts with your writing? Is it difficult to find time to write, between teaching, managing social media for AGNI, and participating in many literary events? Do you tend to carve out specific blocks of time each day, or do you write when the muse strikes you?

I find that living and writing inform each other, especially when I’m giving myself permission not to write when I need to. (Some weeks or months of the semester, all I can do is teach and sleep — and I’m a much happier artist now that I’ve learned, or am starting to learn, the act of forgiveness.) Teaching also makes me a better writer. Hearing my students interact with texts, watching them close-read poems and reading their interpretations of a short story — that all enriches my own facility with language, and engages a nascent curiosity that I sometimes forget still exists within me when I sit down to read a new book.

It is, always, difficult to find time to write. I make myself do it. Sometimes the muse strikes and I yell those lines into the recorder on my phone, or jot them down on the back of a receipt. When I’m actually sustainedly productive, though, is when I set small writing goals (for me, they’re almost always measured in time, not product), and meet them. An hour early in the morning a few times a week is how I wrote my latest project (different from Salt and The Glad Hand of God Points Backwards). My life will never simplify enough for constant production — and that’s a good thing, because the life and the art speak, and learn each other, and they grow together. And both of them are me.

“My life will never simplify enough for constant production” seems like a mantra I could repeat in front of the mirror. Thank you so much for taking the time to discuss your life, the world, and your writing in it!

Thank YOU for your thoughtful and engaging questions, Joey! I’m so grateful.

Find out more at rachelmennies.com, or follow Mennies on Twitter @rmennies.

Joey Lew is a MFA candidate in poetry at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She holds a Bachelor of Science in chemistry from Yale University, where she was a member of WORD: Spoken Word Poetry. An interview that she conducted with poet Nicky Beer was published this month in Diode, and she has two book reviews forthcoming in Tupelo Quarterly.