Nonfiction by Gavin Tomson for MQR Online.

Autofiction, though nowadays in vogue, is far from new.

Serge Doubrovksy, the French writer and critical theorist, coined the term autofiction in the 1970s to define a few of his own novels, including Fils (1977), in which he stirred together fiction and autobiographical facts. But novels that one could retrospectively label autofictional date back further.

A century before today’s best known, or at least most notorious, autofictional novelist, Karl Ove Knausgård, wrote unusually thick novels like Min Kamp featuring real people who got mad at him for writing the books, Proust wrote even thicker novels: A la recherché du temps perdu (1913-1927) featured real people who got mad at him for doing more or less the same. (Proust penned many detailed letters to Laure Heyman, trying in vain to persuade her that she had not been his model for Odette Crécy.) These days, then, we are not witnessing the sudden birth of autofiction as a popular literary form. Rather, we are witnessing its rebirth. Autofiction rises again.

It’s no shock that publishers today promote autofictional novels by the likes of Knausgård, Jenny Offill, Sheila Heti, Teju Cole, Ben Lerner, and Rachel Cusk, to name a few, as trailblazing works of art that burn new pathways in literature and in readers’ neurons. Trailblazing works of art are hot commodities, and hot commodities sell. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, for example, claims on its website that Book 1 of Knausgård’s My Struggle is a “rare work of dazzling literary originality.”

What does shock is how some writers today speak about autofiction as though the form were not at least a century old. David Shields is one such writer. In Reality Hunger, his manifesto on genre and contemporary literary style, a book that has aged as well as an avocado, Shields states that “[a]n artistic movement, albeit an organic and as-yet unstated one, is forming.” What are its “key components”? Sheilds responds with a list:

A deliberate unartiness: “raw” material, seemingly unprocessed, unfiltered, uncensored, and unprofessional…. Randomness, openness to accident and serendipity, spontaneity; artistic risk, emotional urgency and intensity, reader/viewer participation; an overly literal tone, as if a reporter were viewing a strange culture; plasticity of form, pointillism; criticism as autobiography; self-reflexivity, self-ethnography, anthropological autobiography; a blurring (to the point of invisibility) of any distinction between fiction and nonfiction: the lure and blur of the real.

Browsing through this list, it’s tough to tell how exactly these components comprise an organic artistic movement, because none of them are strikingly new. He does write, at the very beginning of his manifesto, “Every artistic movement since the beginning of time is an attempt to figure out a way to smuggle more of what the artist thinks is reality into the work of art.” If that is true, it’s equally true that every writer since the beginning of time who commences an argument with “since the beginning of time” has not done his research.

I should say, in Shields’s favor, that one of his “components,” namely “deliberate unartiness” — a trendier term is “messiness” — though not new, is definitely more popular among writers today than it was a hundred years ago, when Proust penned mannered letters to angry gentry whom he artfully characterized in his polished books. Defenders today of such unartiness, like the dubiously trendy Sheila Heti, author of the deliberately messy autofictional novel, How Should a Person Be? — which comes frosted with a sugar-high blurb from Shields — claim that deliberately messy, purposefully unartful works smuggle more reality into them than polished works. Messy works are more verisimilar than their neater counterparts. Unartful art is more like life than artful art. Unartful art contains more life. How Should a Person Be? is subtitled, A Novel from Life.

But the concept of deliberate messiness is itself messy. Isn’t the very impulse to write fiction born of a frustration (however vague or unconscious) with the messiness of experienced reality, twinned with a desire (however irrational or doomed) to shape it with carefully chosen and placed phrases, scenes, dialogue, images, and so forth? As James Woods observes in a review of Atonement by Ian McEwan, “There is no such thing, really, as a confused or truly messy fiction; distortion is built into the form like radon underneath sick buildings.”

Even an ostensibly messy novel like How Should a Person Be? is meticulously shaped. (Heti did take seven years to write it.) So-called deliberate messiness, when done well, is just another diligent shaping principle. When done poorly, by contrast, messiness is just a mess. I’m skeptical of writers today who label their works “deliberately messy” because far too many do so to mask their works’ flaws as strengths.

Besides, literary reality is not beholden to actuality. Fictional prose need not be “from life” to be lifelike. In The Red Badge of Courage, Stephen Crane depicts the Battle of Antietam so convincingly that a veteran later swore he fought alongside Crane — but Crane never fought in the Civil War. Conversely, there are innumerable stories about real people, places, and events that do not convince readers of these people, places, or events. Aristotle expresses succinctly the point at stake when in Poetics he argues that for the purposes of literature, “a convincing impossibility is preferable to an unconvincing possibility.” Something which did not happen in life but which reads as though it did is preferable to something which did happen in life but which reads as though it did not.

Shields speaks tendentiously about his hunger for “the real,” but perhaps what he actually desires is to be convinced by what he reads. Shields titled his manifesto Reality Hunger, but if Reality Hunger had an unconscious title, it would be something like Conviction Desire. It’s no coincidence that hunger, according to Freud, is not only one of the most fundamental desires, but also one of the easiest to satisfy: a baby hungers for his mother’s milk and his mother gives or withholds, satisfies or frustrates. Shields, hoping to satisfy a desire to be convinced by what he reads, reduces his frustrated desire for conviction to a simple (and more marketable) hunger for the real. But the desire for conviction will not be satiated by a work “from life” if this work isn’t lifelike. Possibilities are not convincing merely because they’re possible.

A frustrated Shields also manifests his complex desire for conviction as a disdain for artifice — what, in his mind, makes so much prose feel fake. Yet fictional artifice is not his proper target, because it’s actually because of artifice that writers render impossibilities convincing. I was most convinced, recently, by a fictional impossible while reading the very choreographed, very melodramatic, very symbolic — which is to say, very artificial — scene in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, where Anna and her husband, Aleksey Aleksandrovich, are seated near (though not next to) each other at a race track, while below them Vronsky races his beloved horse, Frou-Frou. Aleksey is suspicious that Anna loves Vronsky, and so, rather than watching the race, he watches Anna watching the race. Noticing how Anna’s eyes are fixed the whole time on Vronksy, even when another equestrian suffers an accident, Aleksey admits to himself — finally — that his wife is in love with Vronsky.

It’s a tragic scene, and only after reading it for the first time did I realize that I’d been reading something, as opposed to experiencing it as I would in real life (or in those dreams that somehow feel more real than life). Tolstoy beguiled me into believing utterly in his convincing impossibilities. And he accomplished this with artifice.

Compelling prose beguiles, as if by a sort of highly sophisticated conjuring trick, a sublimated breed of magic, which the author performs, on his readers, with help from artfully chosen artifice. And contemporary autofiction that blurs together the real and the fake “to the point of invisibility” is no exception to this rule. What makes an autofictional novel compelling is what makes a big ol’ realist novel like Anna Karenina compelling. Both novels convince their readers that what is happening, while reading, is really happening. Both allow readers to experience what takes place on the page as real life.

So why, today, is autofiction making such a comeback? What does it do, or appear to do, that other forms do not? My guess is that, given how in our ethos, in the age of social media, privacy is passé and the personal is public, many readers want from their authors what they want from their friends on Facebook: personal transparency. Authors of autofiction are more likely to appeal to readers today because these readers are more willing to suspend their disbelief for writers who write “from life” than writers who write from elsewhere.

Readers today are also more willing to relate to an author who writes “from life” than an author who writes from elsewhere. Certainly it’s no coincidence that the rebirth of autofiction as a widely popular literary form coincides with the birth of what Rebecca Mead calls, in her so-titled essay for the New Yorker, “the scourge of ‘relatability.’” One hundred years ago, when Proust published the first volume of A la recherché du temps perdu, the term relatability did not mean what it means today. One hundred years ago, Mead notes, “if someone said something was ‘relatable,’ she meant that it could be told — the Shakespearean sense of “relate” — or that it could be connected to some other thing.” Nowadays, however, when someone says something is relatable, she means she can identify with it. (Everything is about me!) And relatability has quickly become a key criterion of aesthetic judgment. Consumers want reality TV shows and novels and pop songs and Shakespeare to be relatable. It’s relatability or bust. “Shakespeare,” tweeted Ira Glass in 2008, after watching a performance of King Lear in the park, “[is] not good. No stakes, not relatable. I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks.” Autofictionalists are relatable and therefore they don’t suck. Readers are more willing to relate to, identify with, and also rely on a narrator who resembles her author more than a narrator who does not. Relatability, nowadays, means readability. Autofiction is readable because it’s relatable. Knausgård: very good. High stakes, super relatable. I think I’m realizing: Knausgård rocks.

It’s easy, of course, to get all snooty about relatability as an aesthetic criterion. I’m more interested, however, in the ties between relatability and conviction. I’m more interested in how a reader’s desire to relate to, identify with, and rely on an autofictionalist influences her willingness or capacity to be convinced by his prose. What a reader relates to reveals more about how she wishes to see herself, or who she would like to become, than who she is. What a reader relates to reveals more of her ego ideal than her ego.

If, hypothetically, I try while reading My Struggle to relate to Knausgård, I try to see myself as being like Knausgård, or capable of becoming more like him. Sure, some readers are content simply to admire autofictional authors without envying them; as Nietzsche aphorizes in Beyond Good and Evil, “There is an innocence in admiration: it is found in people who do not realize that they themselves might also be admired some day.” But for readers who want to be admired in roughly the same way in which they admire Knausgård, relating to him means envying him, and his autofictional novels serve as clues for to how to become more like him.

So, if the autofictional novel does something today that other fictional forms do not, it’s that it encourages a special sort of what Shields calls “reader/viewer participation” — just not in the way he envisions. A contemporary autofictional novel compels readers to search for themselves in its author in such a way that other novels do not. Another way to say this is that the autofictional novel today interests readers differently than other sorts of novels. “The only obligation,” wrote Henry James in his 1884 essay, “The Art of Fiction,” “to which in advance we may hold a novel without incurring the accusation of being arbitrary, is that it be interesting.” A contemporary autofictional novel interests readers in a certain special way.

Of course, reading a novel to relate to its author is a naïve way of reading. Yet to dismiss outright this way of reading on the grounds that it is naïve is to ignore how deeply it makes sense today — and not only for “general” readers, whatever that means, but also for critics, or writers, or editors or professors or grad students — anyone who is supposed to know better. In a hyper-individualistic ethos that overemphasizes self-sufficiently, of course one is tempted to read another self to see whether his own self suffices. Of course one is tempted to relate to, identify with, and rely on an author so that he might in turn rely on himself. What, after all, does one have today besides himself? In the quixotic sixties, love was all we needed. Nowadays, the self is all one has.

“Perhaps it is only in childhood,” ponders Graham Greene in The Lost Childhood and Other Essays, which he published in 1951, “that books have any deep influence on our lives. In later life we admire, we are entertained, we may modify some views we already hold, but we are more likely to find in books merely a confirmation of what is in our minds already…” My (hypothetical) desire to relate to Knausgård is also the desire to confirm to myself that what is in his mind is also in mine, or could be in mine. Greene goes on to say that the adult reader wants his own features “reflected flatteringly back” at him, as though novels were prettifying selfies. By reading My Struggle to relate to Knausgård, I try to see a more flattering image of myself. I (hypothetically) read My Struggle not only because I aspire to be like Knausgård, but also because I want his books to show me how. Contemporary autofiction, in this sense, is a relatable form of self-help. I read the story of another so that it might one day become the story of myself. If I do not see myself in the author, then how can his story help me? He can’t help me. He’s useless. “Shakespeare: not good. No stakes, not relatable. I think I’m realizing: Shakespeare sucks.” (Everything is about me!)

Yet it’s precisely this way of reading, however much it makes sense today, that prevents readers from being convinced by an autofictional novel — in such way that leads these readers to hunger mistakenly for “the real,” as Shields does. If I read Knausgård to find in his books merely a confirmation of my thoughts and beliefs, I prevent myself from being changed. And if I prevent myself from being changed, I also prevent myself from having an experience. Experience, after all, is that which changes me.

“What we learn from experience,” writes Adam Phillips in Missing Out, “is that experience keeps stripping us of dearly held beliefs, about ourselves and about others.” By reading My Struggle to confirm, to myself, that the contents of Knausgård’s mind are the same as mine, I hold on tightly to my dearly held beliefs. I stop myself from having an experience. By stopping myself from having an experience, I stop myself from being convinced. And if I’m not convinced, I very well might start hungering more and more for “the real,” and I very well might speak disparagingly of the “fake,” as Heti does in an interview with The Believer:

Increasingly I’m less interested in writing about fictional people, because it seems so tiresome to make up a fake person and put them through the paces of a fake story. I just — I can’t do it…. It doesn’t make sense to me. And the complicated thing is, I like life so much. I love being among people, I love being in the world, and writing is the opposite of that.

Only by reading an autofictionalist in a way that allows him or her to change my dearly held beliefs about myself and others might I permit myself to have an experience that is like being among people in the world. Writing might indeed be the opposite of being in the world, as Heti says, but reading need not be. Words can form convincing worlds — remember?

Compelling prose is convincing prose and, oddly enough, what makes contemporary autofiction interesting to readers today is not what makes it convincing. What makes much contemporary autofiction interesting to readers today is actually what prevents it from being convincing. To read a work to relate to its author, to read in order to have one’s views reflected flatteringly back — this is to have one’s dearly held beliefs confirmed, rather than challenged (let alone stripped away); it is to prevent oneself from having a lifelike experience; from being convinced. Only by reading not to relate might a reader experience, and so be convinced by, an autofictional novel — or, for that matter, a regular ol’ realist novel, like Anna Karenina. After all, a convincing impossibility, like Proteus, can pretty much take any form.

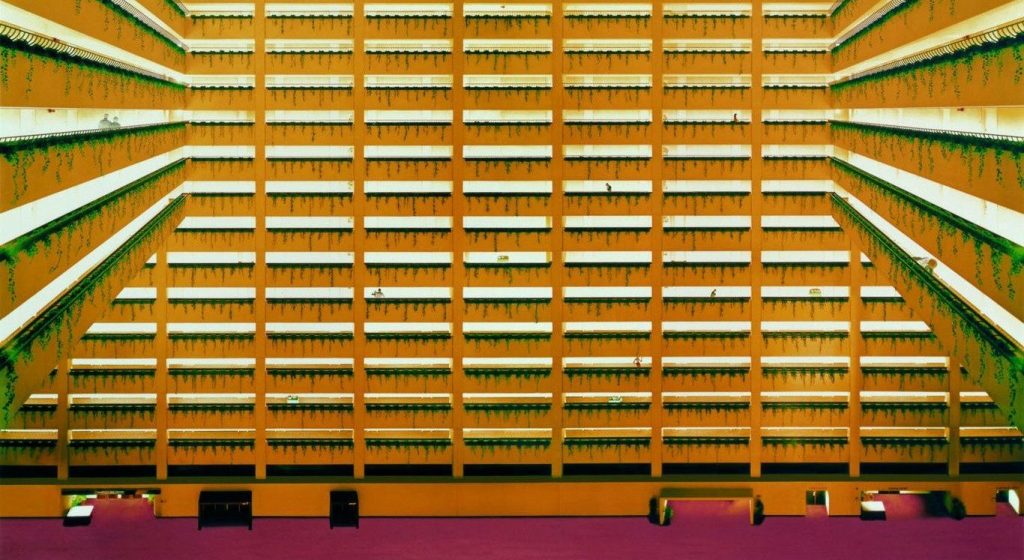

Image: Gursky, Andreas. “Times Square, New York.” 1997. Chromogenic color print. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Gavin Tomson’s nonfiction has appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly Journal and The Walrus. He’s currently a Felipe P. De Alba Fellow and MFA (Fiction) Candidate at Columbia. Find him on Twitter @GavinTomson.