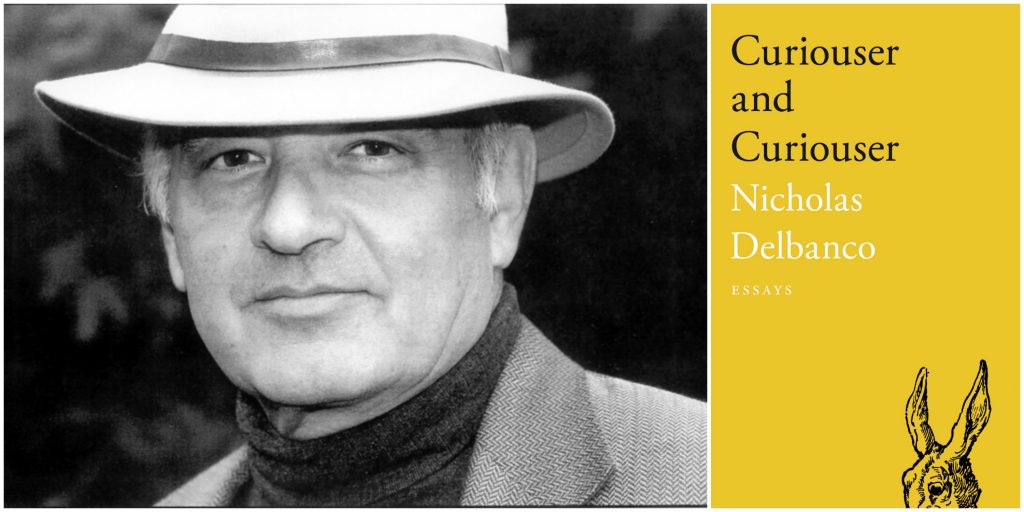

Curiouser and Curiouser, the latest nonfiction title by Nicholas Delbanco, features an eclectic mix of musings on art and culture that carry the reader across the varied landscapes of the author’s life and imagination: we move from the present-day halls of the National Gallery to the back roads of France prior to German occupation; we visit a highly-methodized garbage facility in Cape Cod; we wait in the sobering halls of an intensive care unit as a well-meaning harpist plucks away on her strings.

Released last month by The Ohio State University Press, the collection boasts five essays — each of them richly layered, a blend of autobiographical reflection and cerebral inquiry that serves to contextualize the author’s work within his own colorful life. The collection is part of a new series edited by David Lazar and Patrick Madden seeking to print “the most interesting and innovative books of essays by American writers,” and they have so far not disappointed in this endeavor. The venture has included the creative nonfiction of Phillip Lopate (A Mother’s Tale, January 2017) and Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas (Don’t Come Back, January 2017), in addition to forthcoming work by Catherine Taylor (You, Me, and the Violence, September 2017).

In the book’s first essay, “The Countess of Stanlein Restored,” a piece that originally appeared in Harper’s and was later expanded to a book, Delbanco delves into the intricate restoration of the “Countess of Stanlein ex-Paganini” Stradivarius violoncello of 1707. The essay profiles the cello’s former owner and Delbanco’s father-in-law, the late cellist Bernard Greenhouse, a man so dedicated to his one-of-a-kind instrument that at life’s end he slept with it beside him in bed.  Next in the collection is “A Visit to the Gallery,” in which Delbanco reflects on his early relationship to art and the art world, sketching portraits of his father, an avid collector and painter in his own right, as well as his uncle, a noted art dealer in London. Delbanco’s grandparents on his mother’s side were likewise aficionados, having once owned a painting by Alfred Sisley that was lost to the family during the Second World War.

Next in the collection is “A Visit to the Gallery,” in which Delbanco reflects on his early relationship to art and the art world, sketching portraits of his father, an avid collector and painter in his own right, as well as his uncle, a noted art dealer in London. Delbanco’s grandparents on his mother’s side were likewise aficionados, having once owned a painting by Alfred Sisley that was lost to the family during the Second World War.

At the start of the collection’s third and titular essay, “Curiouser and Curiouser,” the book veers from autobiographical rumination — or so it would initially seem. We are first introduced to our “hero,” the impish primate known the world over as Curious George; then we meet his creators, H.A. and Margret Rey. Now where is this one going? one might ask at the start of the essay. Our attention has been guided from a Stradivarius cello to the subject of museum-as-sanctuary to … a fictive monkey climbing a tree to rescue a bear? Soon, however, we find our feet. The Reys (and George) are very much here for a reason. Like Delbanco’s parents, the Reys fled Europe during WWII, eventually settling into a suburb of New York. Here, we learn, they befriended the young Delbanco family, a revelation both startling and satisfying. It’s not so unusual to forge a connection to the famous people we encounter in childhood, nor is it unusual for those characters to leave a lasting impression — especially when the characters are famous writers and the child in question is a future critic and novelist.

The next essay in the collection, “My Old Young Books,” details the author’s efforts to revise his classic Sherbrookes trilogy for a single-volume reprinting by Dalkey Archive Press. Following that comes the final piece, “Towards an Autobiography,” an essay written over the span of thirty-two years, the bulk of it being laid down in 1985 for inclusion in the Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series. Part II of the essay is the addendum added in 2000 for the volume’s reprint, and Part III of the essay — which now serves as the conclusion — is dated February 2017. It contains, perhaps, some of the collection’s most moving passages, not least of all because of the author’s brush with death, an event he describes in the sort of straightforward, stripped-down language that such an event so often necessitates. For the reader not expecting it, the effect is paralyzing:

Last February I died. Briefly, and two or three times…. “Flatlining” is a medical condition, not all that infrequent after a heart-bypass operation and an aortic-valve replacement, both of which I had.

Of course immediately upon reading the lines, this reviewer made them about herself. What was I doing in late February 2016? I consulted my journal, which showed a preoccupation with two events: the presidential primaries and the fact that I carried my daughter to the E.R. in the same week. (She ran head-first into the corner of the kitchen island; she was fine.) Why this mattered, I have no idea; I suppose I wanted to see what was so important in my own life that I didn’t intuit from one-thousand miles away the near-death experience of my former professor. Truly, Nicholas Delbanco was an important figure from my graduate school years. I was a member of one of the last graduating MFA classes to have him as an instructor prior to his retirement in 2015, and in my second year he served as my thesis advisor. His instruction, it will come as no surprise, proved invaluable.

And so it is with great pleasure that I now have the opportunity to peer into the artistic machinery of my former teacher’s heart and brain. What follows are the questions I sent him via e-mail about his latest work, the experience of writing across genres, and, of course, his plans for the future.

How did you approach assembling the five essays that appear in Curiouser and Curiouser in terms of their order and inclusion in the book?

As I wrote in that collection’s Author’s Note, the arrangement is neither chronological nor, in a certain sense, sequential. Rather, it’s an attempt to map “the private and public arena.” The first person plays a role in each and all of the essays, but two of the long ones — the discussion of “The Countess of Stanlein Restored” and the analysis of “Curious George” — are only briefly “personal.” Music, the visual arts, and, predominantly, the writing of books have all been enduring interests, and the arrangement of these essays — long, brief, long, brief, long — is meant to mirror those concerns. I didn’t, I mean, cluster together all the “literary” essays, then move to music and art. The last piece is an unabashedly personal accounting, “Towards an Autobiography,” that’s as close as I will come, I imagine, to memoir.

In the book’s front matter you acknowledge these essays as having been (more or less) in progress since the new millennium. Since then, you’ve also published a number of novels — What Remains, The Vagabonds, Spring and Fall, The Count of Concord — in addition to one-volume revisions of Sherbrookes and The Years. How much does writing in one form influence another, at least when it comes to toggling back and forth so prolifically?

For the last thirty years or so I’ve “toggled,” as you put it, between fiction and nonfiction, and it’s been my experience that the one mode and genre invigorates the other. A great pleasure of nonfiction is that one has to learn things, to acquire information (as in the histories of Stradivari or H.A. and Margret Rey, for instance), and that’s also true, of course, in such historical fictions as (part of) The Vagabonds and The Count of Concord. The high charge and challenge of writing is to remain interested, and I’ve found myself empowered or at any rate enabled to do so by simply switching gears. To continue with that metaphor, it’s like the difference between driving a clutch car and one with automatic transmission; in the former instance you have to stay alert.

In 2015, you retired from your post as the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English Language and Literature and the Director of the Hopwood Awards Program at the University of Michigan. What was it like to move on from this role after such a long run, and how has it affected your creative output?

My present project is, in fact, a book about teaching — and, specifically, the teaching of fiction, which has been my life’s work. But through all the years of administrative responsibility, as Director of the MFA or the Hopwood Awards, it was always important to me to maintain the habit of writing and to continue to spend hours at the home-based desk. I suspect I would have felt fraudulent had I been preaching a trade I no longer practiced, so I got up every early morning and clacked at the keys. Therefore the business of retirement is no great shock to me, nor an important transition; it’s not as though I worked a forty- or eighty-hour week in some office, then suddenly became a sunbird or golf maven. My “creative output,” such as it is, feels steady as she goes …

“My Old Young Books” takes the reader on a journey through your original composition of the Sherbrookes trilogy (Possession, 1977; Sherbrookes, 1978; Stillness, 1980) as well as the intricate revision process for the trilogy’s reissuing as a single-volume book in 2011. You write, “It’s a simple truth, not boastful, to say those books were widely reviewed and well received; by 1980 I could fairly claim to have finished my apprenticeship and entered into the guild.” I’m curious: how did the completion of such a substantial work of fiction affect your approach to the short story form in the immediate years that followed?

By 1980 I had published ten novels, with the first of them appearing in 1966. That’s by any standard a pretty rapid rate of composition, and I now think of myself, in those early years, as a kind of bumblebee. According to scientific analysis, the bumblebee is too fat, its wings to small, and it flaps them too slowly to ever succeed at being airborne. But, cheerfully ignorant of that assessment, the bumblebee just flies. In some sense that was my experience of novel-writing; I didn’t know how hard it was and therefore simply wrote. Then, as I report in “My Old Young Books,” with the end of the Sherbrookes trilogy the well went dry — or, perhaps, it’s fair to say I was up in the air, wings flapping, and took a look down at the ground and said, “Wow, that’s a far distance to fall and the air is thin up here” and then just went splat! From that time on I’ve alternated forms, as per the previous answer, and also attempted short fiction. The two volumes of short stories — About My Table, which contains nine stories about domestic life, and The Writers’ Trade, nine tales of the professional life — were an instructive pleasure to write, and someday I hope to return to that form. A friend of mine, who also alternates between long and short fiction, says that short stories are far harder; the novel’s a forgiving form, but there’s no room for error in the shorter mode.

What remains for you the hardest part about writing? The most rewarding?

As I wrote at the close of an autobiographical passage in a recent work of nonfiction, The Art of Youth: “Much changes and has changed. But the labor of writing a sentence, rewriting it, rewriting it, is still a labor I love.”

You mention in Part III of “Towards an Autobiography” that had you known fifty years ago what you know today, you may “have done what so many of the young now do — turned to television writing in New York or screenplays in Los Angeles — and worked in collaboration with others. That the epicenter of the ‘the writer’s trade’ has shifted in my lifetime seems inarguable; there’s energy abounding in those genres…” What are some of the recent films or television series you feel particularly impressed by in terms of storytelling, and why?

As you know, I think, my son-in-law Nicholas Stoller has for a decade or so been directing and, latterly, producing films, so I’m honor bound — and happy — to watch them each and all. One of them, “The Five Year Engagement” was in fact set in Ann Arbor, and I had a cameo role as — of all things — a professor! This year our daughter Francesca and he co-created a series for Netflix called “Friends from College,” and I of course watched that too. When not close to home, my tastes run farther afield — to “Cezanne et moi,” a film from France, and “Borgen,” a TV series from Denmark. But truth be told I spend more time in front of a page than screen …

What books are on your list to read in the near future (and would you be daring enough to admit to one or two guilty pleasures)?

For several years running I served on prize juries for fiction — the PEN/Faulkner Prize, the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, etc. And for each of those contests it proved needful to read — or at least to turn the pages of — several hundred books per annum. It’s rather like the tale, perhaps apocryphal, of a baker who made a chocolate-loving young man his assistant and told him he could eat all the chocolate he wished. After a month or two the apprentice had no sweet tooth left or stomach for what was displayed on the bakery shelves, and sampled none of the wares. I feel a little that way. My “guilty pleasures,” such as they are, consist now largely of nonfiction: history, biography, travel texts. Next fall I’m going to lead a New York Times Travel Tour aboard “The Orient Express,” so I’ll have to brush up on Agatha Christie, et. al.

Can you speak to what you’re working on now?

I’ve been working on a pair of novels, one, a historical fiction based on the life of Stephen Crane’s widow, Cora, and called The Work of Love. And one a kind of family saga, provisionally titled (no doubt appropriately) It Is Enough. Also that teaching text to which I referred here above. Perhaps this is a function of retirement and diminished sense of urgency, but I no longer feel the need to publish a book a year or bring a project to published completion. Right now it seems fine to have several projects to pursue. As to their specifics, I’m going to plead for silence and exile, if not cunning. To go into greater detail would obviate the need to write it down …

Curiouser and Curiouser: Essays is out now from The Ohio State University Press. Find out more about Delbanco’s writing and upcoming projects at nicholasdelbanco.com.