Whenever I’m asked to recommend a modern Iranian novel, I have to keep three things in mind.

First, unlike Persian classical literature—the works of such masters as Rumi, Khayyam, and Hafez—the modern novels are not widely known or usually excerpted in anthologies of world literature. The novel is a fairly new medium for Iranians. There also has been no Nobel prize-winner to bring attention to contemporary writings, like Naguib Mahfouz for modern Arab authors. If Westerners have read or heard of any recent Iranian book, it is probably a memoir written in the West, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis or Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran.

A second issue is the lack of translations, a common problem in world literature. Very few works of modern Iranian literature have been published in English, in Iran or abroad, and that includes roughly just forty-five novels or novellas over the last fifty years. All the languages of the world are vying to be among the few foreign-language books published in English—it’s a crowded beauty contest like the foreign film category of the Oscars. Furthermore, many of the translated works are now out of print, or the translations are not good. Novels by important Iranian authors—for example, Bozorg Alavi, Jalal Al-e Ahmad, Hushang Golshiri, Abbas Maroufi, and Esmail Fassih—are out of print, and very few translated works have been published by major American presses with good distribution and promotion.

The third issue is the way the literature is read. To begin with, you can’t assume you are working with some aspects of the original text, such as music and syntax, when reading a translation. The elegance of prose in the translation has a lot to do with the work of the translator. In the case of Iranian translations, we unfortunately have less elegant results. Moreover, most readers of Persian literature, including my students, are more interested in the historical and sociopolitical details than the literary merits. In my classes, I assign readings to help inform their historical curiosity, including such books as A History of Modern Iran and Iran Between Two Revolutions by Ervand Abrahamian, and Modern Iran: Roots and Results of Revolution by Nikki R. Keddie. But this curiosity can be both a blessing and a curse. Given the current political situation, the interest in Iranian literature is greater than in the works of many other languages. Readers want an alternative or truer narrative to the Iran presented in the American media over the past thirty-eight years. However, this demand also determines what is being read, published, and translated. In my classes, for example, I have to not only sometimes forgo the formal analysis but also consider what images of Iranian are re-enforced or dispelled by the works.

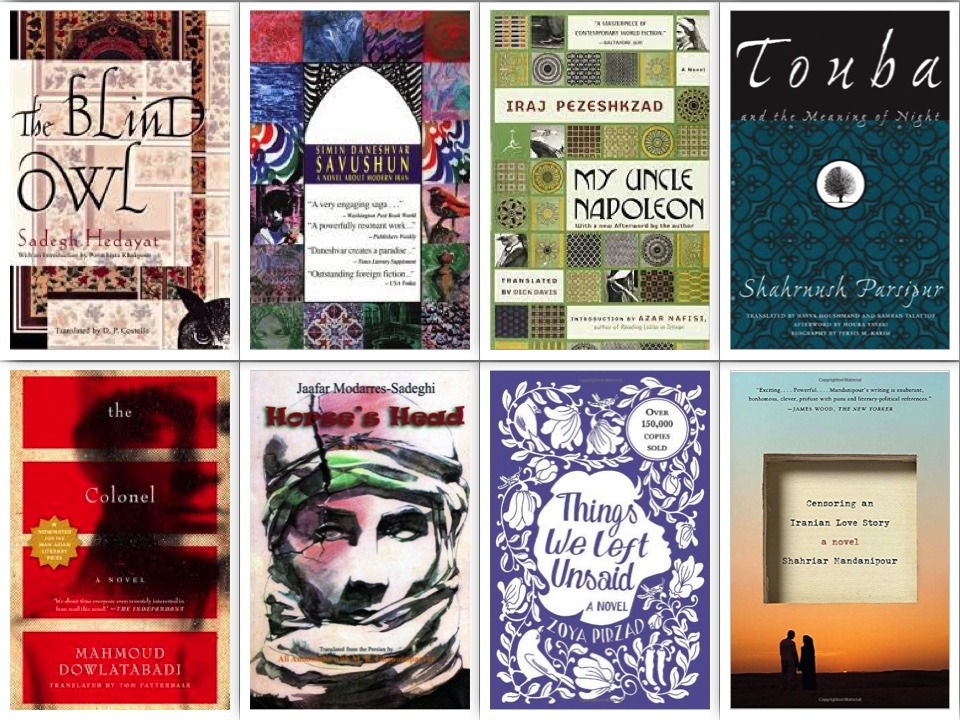

I will discuss here a handful of Iranian novels that are well-translated and in print, as good representations of modern Iranian writing. I have also highlighted the political and historical context.

Books from before the Islamic Revolution

I would like to begin with three major novels from before the Islamic Revolution, which represent a nice range of writing from experimental works to social realism to satire. If you are interested in the Constitutional Revolution period (1905-1911)—which was the first modern reformist movement in the Islamic world—I suggest Gholam-Hossein Sa’edi’s The Cannon translated by Faridoun Farrokh. For a work that deals with 1953 Iranian coup d’état and Prime Minister Mohammad Mosadegh’s overthrow, another pivotal moment in modern Iranian history, see Ahmad Mahmoud’s The Neighbors translated by Nastaran Kherad.

Sadegh Hedayat (1903-1951) is possibly the most influential modern Iranian prose writer. His masterpiece, Buf-e Kur (“The Blind Owl”), was published in 1941. In The Politics of Writing in Iran, Kamran Talattof calls the novella “Iran’s most controversial and celebrated work of fiction” (58). Other works of Hedayat have also been translated, including a selection of short stories as Three Drops of Blood and Other Stories, which provides a good range of Hedayat’s writing from naturalism to surrealism.

The Blind Owl was the first modern Iranian novel to be translated into English. It was translated by Desmond Patrick (D.P.) Costello in 1957 and later by Iraj Bashiri in 1974 and Naveed Noori in 2011. Bashiri revised his translation three times, the most recent version became available online in 2013. Even with its problems, Costello’s translation is still a good read and remains the most popular. To see the work’s more formal experiments, read Noori’s translation. The work has also been adapted four times into movies, including by influential Iranian-American experimental theater director Reza Abdoh in 1992 and by the great Chilean filmmaker Raúl Ruiz as La chouette aveugle in 1990.

Porochista Khakpour, in her extended introduction to the Grove Press edition, begins by describing how her parents forbade her to read the book, something that I, like many Iranians, have also experienced. She describes the book as “the most disturbing thing I have read.” Some readers have viewed it as a critique of the Reza Shah’s rule, though the book is about much more. M. R. Ghanoonparvar, in Prophets of Doom, says the book reveals “Hedayat’s terrible awareness of change taking place in the Iranian psyche, Iranian society and social institutions.”

As told by an unreliable narrator, The Blind Owl’s complex and macabre existential tale has confounded readers and critics alike. It recalls works by visual artists like Egon Schiele and Edvard Munch in its hallucinatory parallel story of a misanthropic male protagonist’s sexual anxiety and fear of death. You can see the influence of mysticism, Hinduism, and Khayyam, as well as such Western writers as Rilke, Poe, and Kafka, and Western genres, like expressionism and gothic fiction. Many books and essays have been written about this enigmatic book.

At the early stages of the novel’s development in Iran, this most influential novella paved the way for experimentation to be a prominent part of Iranian prose and for more important experimental works to be published. If you are interested in experimental writing, three examples of such innovative works written before the revolution are: The Prince by Golshiri translated by James Buchan, The Patient Stone by Sadeq Chubak translated by Ghanoonparvar, and Malakut by Bahram Sadeqi translated by Kaveh Basmenji.

Simin Daneshvar (1921-2012) was the first Iranian women to publish a novel and a collection of short stories. As Fulbright fellow in 1952-54, she studied creative writing with Wallace Stegner at Stanford University. She also married the acclaimed Iranian writer and thinker Jalal Al-e Ahmad.

Her first novel, Savushun (1969), which has sold more than half a million copies, has been translated twice into English, with more exacting language by Ghanoonparvar in 1990 and by Roxane Zand as A Persian Requiem in 1991. Hassan Abedini, in Sad Sal Dastan-nevisi-ye Iran (“One Hundred Years of Persian Prose”), writes that Savushun, with its poetic, precise, and strong prose, started a new season in the history of prose in Iran. Two collections of short stories are also available in English: Daneshvar’s Playhouse (1989) translated by Maryam Mafi and Sutra & Other Stories (2008) translated by Hasan Javadi and Amin Neshat.

Set in the later years of WWII, when the British occupied Iran, Savushun is the story of a landowning family in the city of Shiraz, where Daneshvar grew up. The narrator, Zari, is a wife and mother who is concerned about the safety and happiness of her family while her patriotic husband gets involved in the greater community against imperialism, tribal politics, and corruption. It is a story of the growing social and political awareness of Zari, as well as a growing revolutionary social consciousness. Farzaneh Milani, in Veils and Words, writes that Savushun “presents a world in which not only do the characters function fully and have the freedom and the ability to speak for themselves but the plot is also highly plausible, culturally, socially, and historically.”

Daie Jan Napoleon (1973), written by Iraj Pezeshkzad and translated as My Uncle Napoleon by Dick Davis in 1996, is another Iranian best-selling novel set during the WWII Allied occupation of Iran. But instead of being another social realist work, My Uncle Napoleon is a social satire, a tragicomedy full of puns, ludicrous characters, farcical conflicts, sexual innuendo, and imaginary enemies and battles. It also references the earlier Constitutional Revolution period (1905-11), when the Iranian government was subject to the British and Russian imperialism. However, unlike the revolutionary response to British imperialism in Savushun, My Uncle Napoleon makes fun of the common belief that the British are behind all important political events in Iran. In fact, Iranians use the name “Uncle Napoleon” to refer to conspiracy theorists.

Looking back from the 1960s, the narrator of the novel tells the story of his first teenage love and growing up in an extended family under patriarchal rule, aristocratic pretensions, power struggles, and petty family dramas. Azar Nafisi, in the introduction to the 2006 Random House’s Modern Library series, writes that despite being “highly critical of the society it portrays, it is also the best testament to the complexity, vitality, and flexibility of Iranian culture and society.” The book presents a changing society transitioning toward modernity.

In 1976, My Uncle Napoleon was made into a popular television series by Nasser Taghavi, a leading Iranian filmmaker. Pezeshkzad and Taghavi produced some of the most distinct and memorable characters in modern Iranian culture. Ghanoonparvar, in his book In a Persian Mirror, writes that “Pezeshkzad builds one of the most memorable and remarkably true-to-life, albeit caricatured, character in his very popular novel.” After the Islamic Revolution, the movie and book were banned, though one could easily find an offset copy.

Books from after the Islamic Revolution

I would like also to recommend three different types of books by authors who began writing after the revolution. If you are primarily interested in the Islamic Revolution, unfortunately, there are no specific translations of good books published in Persian and in Iran. However, there are many good memoirs or novels written by exiled writers, mostly in the languages of their host countries, that deal with this important period in Iranian history. Marjane Satrapi’s comic memoir Persepolis, originally written in French and later also made into a film, is the most well-known case. An example of an expat writing in Persian is Taghi Modarressi (1931-1997), who wrote ‘Azra-yi khalvat’nishin about a transplanted Austrian woman and her grandson at the time of the Islamic revolution. The book is translated as Virgin of Solitude (2008) by Nasrin Rahimieh. But I will not discuss such books here, given their number and the fact that the Iranian books are not translations and the diaspora writers work are not part of the literature being read in Iran.

Just as there are plenty of books on the Iranian Revolution, there are also a lot of books on the Iran-Iraq War, one of the longest wars in the twentieth century. But unlike the books on the revolutions, these translated works were best-selling novels promoted by the government. We still miss translations of important books, such as Zemestan-e 62 by Esmail Fassih. Novels that are available in English include: Journey to Heading 270 Degrees by Ahmad Dehqan and Chess with the Doomsday Machine by Habib Ahmadzadeh both translated by Paul Sprachman, Fortune Told in Blood by Davud Ghaffarzadegan and Eagle of Hill 60 by Mohammad Reza Bayrami translated by M.R. Ghanoonparvar. Paul Sparchman also translated the memoir One Woman’s War: Da by Zahra Seyyedeh Hoseyni. Thirst by Mohmmad Dawlatabadi, whom I will discuss later, has been published in the West but is banned in Iran. These books will give you a good understanding of the different ways Iranians confronted the subject of the war. But there are too many books to discuss here. For a brief survey of the fiction from this period, see the chapter “War in Fiction” in Iranian Film and Persian Fiction by Ghanoonparvar.

Kalleh-ye Asb (1991), written by Jaafar Modarres-Sadeghi and translated as Horse’s Head (2015) by Ali Anooshahr and M. R. Ghanoonparvar, is a good example of a work that deals with issues of the Kurdish minority in Iran. Moderres-Sadeghi is a prolific writer, who has written seventeen novels. His classic novella Gavkouni (1983), an innovative experimental work, is also available as The Marsh (1996) in a translation by Afkham Darbani and Dick Davis.

Horse’s Head, the second part of a trilogy, is a love story between Kasra, a married man from Tehran, and Jahan, a young Kurdish girl. Much of the book covers the concerns of Kurds and the start of the Iran-Iraq War with its impact on the Kurdistan region. Kasra tries to persuade Jahan to leave a militant party for Kurdish independence, while she tries to get him to join. Kasra ends up going to Kurdistan to look for Jahan. Typical of Modaress-Sadeghi’s work, the protagonist (Kasra) is in search of a purpose, and there is much psychological and philosophical discussion and contemplation. There is also tension between love and war, living a normal life and fulfilling obligations to a cause or party. The book went through two printings before getting banned. Today, it cannot be easily found in Iran.

Zoya Pirzad, the second Armenian women to publish a novel in Persian, is a great example of a minority writer who is also one of the best Persian writers. Her work is infused with the culture of Armenians. Pirzad has received France’s Chevalier of Legion of Honor. Her best-selling novel, Cheragh-ha ra man khamush mi-konam (“I’ll Turn Out the Light”), won the prestigious independent Golshiri Literary Award (2002) and the best literary book of the year prize from the Ministry of Culture & Islamic Guidance (2003). The translation by Franklin Lewis was published in 2012 under the title Things We Left Unsaid (which Lewis told me was not his decision). In 2014, the translation of Pirzad’s Yek Ruz Mande be Eid Pak (“One Day Left Until Easter”) (1998) by Amy Motlag was published as The Space Between Us.

Things We Left Unsaid is set in Abadan—a city built around a major old refinery—in the early 1960s during the era of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Pirzad, who was born and raised in Abadan, writes with great precision and detail about a woman’s everyday experiences and emotions. Her style is casual, natural, and subtle, which was new for Iranian novels. The narrator, Clarice Ayvzaian, is an unfulfilled Armenian housewife whose life changes when Emile and her family move next door. Clarice slowly finds herself falling in love with Emile as the families’ lives get entangled. She also gets involved with the women’s movement. Although the book does provide a sense of the place, and references to social events such as women’s suffrage and the Armenian genocide, it is not a political or social realist novel. Most readers in the West, especially if they have lived in suburbs, can easily identify with the narrator, which is significant because, after all, we often share similar experiences in our everyday lives even when we live in very different parts of the world.

Censoring an Iranian Love Story (2006), written by Shahriar Mandanipour, is an example of a book written in Persian by a known Iranian author living in exile. Mandanipour, one of the best Iranian writers, has lived in the U.S. since 2006. He has won a number of prizes, including the Golden Tablet Award in 1998 for writing the best fiction of the past 20 years in Iran. Censoring appeared first as translation by Sara Khalili and is not available in Persian. Unlike most of the Iranian books in translation, it was also published by W.W. Norton and received attention and reviews in the media. For example, James Wood observed in The New Yorker, “Mandanipour’s writing is exuberant, bonhomous, clever, profuse with puns and literary-political references.” The Greek translation of Censoring won The Athens Prize in Literature in 2011.

Censoring is a postmodern novel–a surrealistic and ironic tale within a tale. The first story, identified by bold text, is a modern love story between two youths named Sara and Dara, who meet at a political protest. Their challenge is how to get together given the limitations in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Their story is set in a meta-fiction narrative in which the writer’s alter-ego, Shahriar, is in discussion with a censor, Petrovich, about writing. The book becomes an absurd voyage through the labyrinth of censorship in Iran. We can also see the use of self-reflexivity which became a hallmark of Iranian cinema, as seen in the work of filmmakers like Abbas Kiarostami. Coincidently, The Blind Owl also appears as a banned book that Sara wants to read.

Sweeping History

I want to finish with two great novels that provide a more sweeping commentary on Iranian history. Both these authors, Sharnush Parsipur and Mahmoud Dowlatabadi, began writing before the revolution but produced their major works after the revolution.

Along with Daneshvar and Goli Taraghi, Parsipur is one of the three Iranian women who published a novel before the revolution. She has also won numerous prizes, including the Lillian Hellman/Dashiell Hammett Award, the Italian literary award Premio Feronia-Citta di Fiano Prize, and the Persian Heritage Foundation’s Latifeh Yarshater Award for lifetime achievement.

Translated by Havva Houshmand and Kamran Talattof, Tuba va ma’na-yi shab (“Touba and the Meaning of Night”) (1989) follows a spiritual journey of the heroine, Touba, as well as her daily struggles in a patriarchal society from when she is a young girl until her death. Parsipur creates extraordinary characters. The different women in her novels are complex and alive. They may be ordinary and petty or wise and radical. They go beyond the Western or Iranian cultural and gender stereotypes. Touba is also a panoramic history of Iranian women in the twentieth century and of the changes in Iran from the final days of Qajar dynasty and the Constitutional Revolution to the Islamic Revolution. Many issues—such as religion, marriage, family, class, politics, philosophy, sexuality, tradition, and modernity—are dealt with in the book.

Influenced by authors like Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Parsipur weaves together magic realism and modern innovations in the novel with classical myths and Middle Eastern storytelling that harks back to 1001 Nights. She incorporates diverse works such as the Attar’s classical Persian text The Conference of the Birds and Hedayat’s experimental work The Blind Owl. Her writing brings together the real and magical, polemical and lyrical, rational and mystical, public and private, historical and mythical, traditional and modern, east and west. With their multiple, sometimes even contradictory, perspectives, the novel becomes a prism of Iranian society, echoing the lives of its citizens. As Houra Yavari writes in the afterward, “[Touba’s] story is a spiritual quest. But at the same time, like the tree, [she] has deep roots in the soil of her native land, and her story is also the story of Iran in a turbulent century of change” (340).

Parispur’s best-selling novella Women Without Men, also published in 1989, was translated twice—by Kamran Talatoff, originally for Syracuse University Press (2004), and by Faridoun Farrokh for The Feminist Press at CUNY (2012). It was made into a movie in 2009 by Shirin Neshat, the renowned Iranian-American artist. Sara Khalili has also translated an extended selection of Parispur’s prison memoir as Kissing Sword (2013).

Dowlatabadi is possibly the most respected Iranian novelist living in Iran. He is the author of many books, including the magnum opus Kelidar (1978-1983), a ten-book saga of a nomadic Kurdish family. He has also won numerous prizes, including France’s Chevalier of the Legion of Honor and prestigious Golshiri Lifetime Achievement Award. His novel The Colonel, which took twenty-five years for him to consider finished, has not been published in Persian or in Iran. But translations of the work are available in numerous language, starting with German in 2009. The novel has won praise and such awards as the Jan Michalski Prize for Literature. It was longlisted for the Man Asian Literary Prize. An English translation of The Colonel by Tom Patterdale was published in 2011. Among his other major works translated into English are Missing Soluch, translated by Kamran Rastegar, and Thirst: A novel of the Iran-Iraq War, translated by Martin E. Weir. Missing Soluch was conceived while he was in prison during the Shah’s regime and written in seventy days after his released.

Dowlatabadi is known for long social realist novels about the devastating decline and transformation of rural life, such as Kelidar and Missing Soluch, but The Colonel is a chamber drama. The book is set in the town of Rasht in the north of Iran at the end of the Iran-Iraq War. The protagonist colonel, who has been stripped of his rank because of murdering his adulterous wife, must confront the consequences of the different paths his children have taken. The colonel’s thoughts cover a period starting with the first modern reform movement by Iranian Chancellor Amir Kabir (1848-1851) and ending with the Islamic Revolution. The result is a hallucinatory recollection of the country’s long history of progresses and setbacks, dreams and repressions, and hopes and disillusionments, during the many movements of reform and revolution. Past and present are molded in a nightmare of eternal return. Like Dowlatabdi’s other powerful works, the writing is unsentimental, dark, and despairing. In The Literary Review (Spring 2012), Matt McGregor wrote, “Dowlatabadi has done something perverse, something almost unforgivable: he’s spun from this muck a beautiful, wretched novel.”