Nonfiction by David McDannald excerpted from our Fall 2016 issue.

Footsteps sounded on the porch as I was recording guitar, three hours beyond dusk in the frigid February dark. Knocks followed, thuds. Gravel in the driveway winding up from the ranch’s locked gate to my cabin had betrayed no crunch of tires turning, the footsteps disconnected from the journey they’d completed to my door. Bought in the seventies by my great uncle Cleaves, the ranch sat in the West Texas foothills between Mount Livermore and the Mexican border.

I propped the acoustic guitar against the wall and pushed aside the microphone. Then reached for the doorknob. It wasn’t even locked. There was no peephole. Whoever stood on the porch could see no structures but those of the ranch’s empty headquarters and a strip of lights fifteen miles distant marking the forgotten town of Valentine.

“Who is it?” I said, though asking seemed absurd, this ritual of neighborhoods. “¿Quién es?”

No answer.

To keep the door closed was to hope that the man—or men—would wander back out into the emptiness. So I opened it.

A bulb inside lit one man on the porch. He was thin, five foot five, bleeding from the eye, hyperventilating, swinging his head, a Mexican in his midtwenties.

“Necesito ayuda,” he said, chest heaving. I need help.

Spanish was a tangled mess in my throat. “¿Qué está—”

Surely he knew that to knock on the door of a West Texas cabin was to risk having a shotgun aimed at his face.

“I’m hurt,” he said in Spanish, motioning toward his knees.

Highway patrolmen had advised the foreman of the next ranch to carry a sidearm for just this sort of encounter. All the guns people had lent me for life on the ranch I’d long ago given back.

The man looked up and met my gaze.

“Show me you don’t have a knife,” I tried to say in Spanish, the adrenaline working against me.

He flared his zippered gray cotton warmup, a single T-shirt beneath it, barely an answer to the winter of the highlands beyond the border. I reached into the fabric hanging under his left arm, mainly to see how he’d react to being touched, for there was no way to guarantee he wasn’t armed without patting him down. And an air of confrontation was not what instinct told me to strike.

I moved back from the door, allowing him in. He grabbed the doorjamb, let go, staggered, gasped. “Water. I need water.” He spoke no English. I stepped through the front room toward the kitchen, measuring how conspicuous were my things: two laptops, a guitar and keyboard, a car beyond the kitchen window. But he didn’t look up. He gulped down the water I gave him, exhaled, held the glass out. “More.” He drank a second glass, a third, and half of a fourth, as I formed a list of essentials to gather: car keys, wallet, passport, things connected to movement, and pepper spray, which I carried when I traveled in African capitals.

“I didn’t have water for thirty-six hours,” he said.

“Sit here.” I could feel my Spanish coming back to me. I pulled out the seat at the head of the kitchen table, middle room of the three-room house, the table equidistant from doors on either end leading back out into the cold and the promise, for me, of safety.

“What’s your name?”

His eyes opened. “Adrián.”

“I’m David. Rest. I’ll make you food.”

I shuttled to the basket on the counter for my wallet and keys and feigned calm strolling into the bedroom for the pepper spray, some defense beyond my hands. Onto the worn wood table before Adrián I set a mug holding a sip of whiskey and I stood over him, maintaining our feeble hierarchy, as he drank, shuddered, and set down the empty mug. “I need more water.” He stood, wobbling on his injured legs.

“Stay there,” I said. “I’ll get it.”

The old custom of welcoming a stranger seemed more likely to disarm a Latin American man of his aggression than a Texan. It was this I’d decided to honor, that I’d decided long ago to honor if the situation came, knowing it might prove naïve. I turned the talk to my family, to humanize myself and to push back against the thought that my living on the ranch alone meant I was disconnected, vulnerable. The man’s feet were pistoning against the floor, his fear endangering, violence a half-step from despair. “Adrián, why are you shaking? I can see you’re nervous. You have no reason to be nervous. Nothing is going to happen to you here.”

He stared at me blankly, eyes watering. He had two children who were with his wife back in Chihuahua. His journey up from Ojinaga, where he’d crossed the border, had taken seven days.

I told him another story about my two brothers.

“You were born three?” he said.

Whenever I heard this question when traveling, which was meant to know whether we’d lost any siblings, I couldn’t help but feel guilty that it was not as relevant for those of us born into the promise of a country a step removed from disease.

“You need to clean that cut beside your eyes,” I said and strode to the bathroom for a washcloth I doused with iodine. I served Adrián what I’d made myself for dinner, yams with vegetables, chicken, and sliced avocado, a meal to drive home how lucky I wanted him to feel for having ended up at my door.

To continue reading “Migrants at the Door,” purchase MQR 55:4 for $7, or consider a one-year subscription for $25.

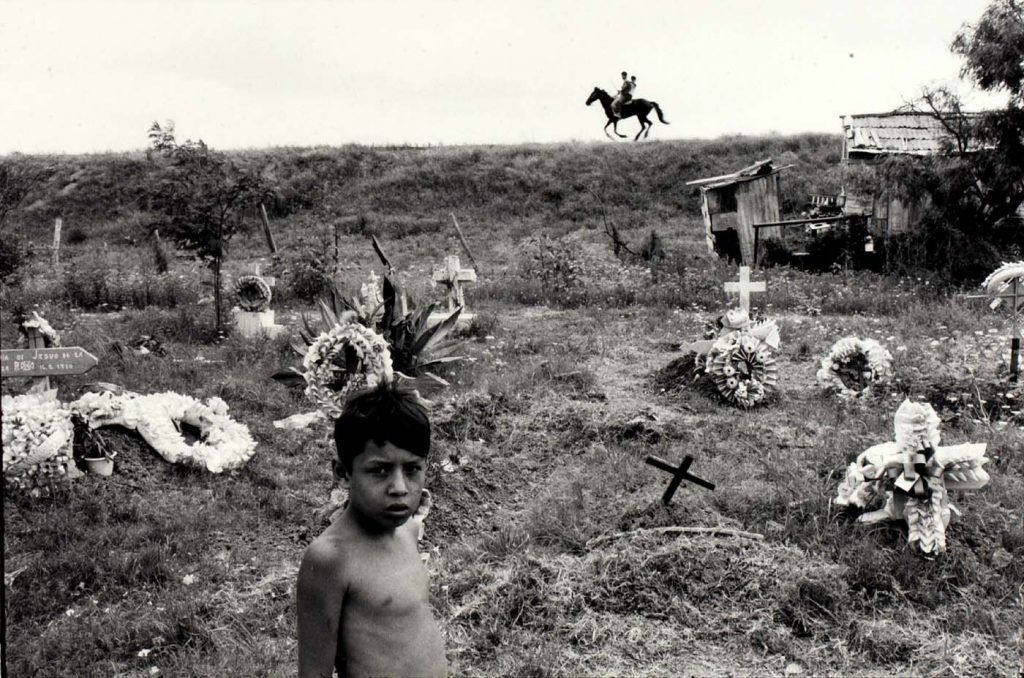

Image: Webb, Alex. “Mexican Border.” 1978. Gelatin silver print. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.