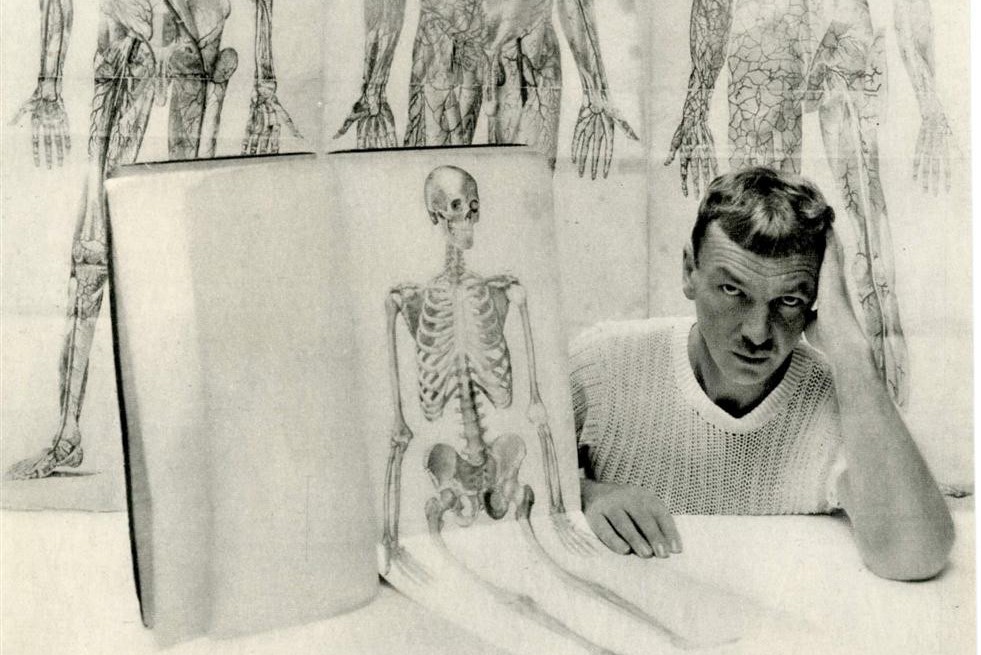

“Poem for George Platt Lynes,” by Wayne Koestenbaum, appeared in the Winter 1998 issue of MQR.

*

George Platt Lynes photographed a naked man, curled

into a snailshell’s infinite regress, and I want

to follow suit, my body a starfish, my skin seized

with a Polaroid purchased on a serious

whim: may I become Lincoln Kirstein or Monroe Wheeler,

wide palms full of fortune, or the sailor

my master of the pick-up

stick picked up and froze in a print

hid in the Kinsey Institute until too recently!

I see so many cuties on 23rd Street, they must be an industry—

members of an international underground élite

gathered to plot the overthrow

of dogma—living replicas

of Lynes’s Orpheus, whose stubble

calls back from pandemonium the foreskins,

pimples and ingrown hairs, each paradoxical

nipple lit like Dietrich’s angel—

I hold sacred the right to look, and will I turn

pornographer? Before falling asleep I was again terrified

nuance would forever resist being enclosed

by a poem, however much it wandered from the point,

so I thought, “Why not say this in prose?”

but then on waking reconsidered, and so I’ll replay dying

Violetta singing farewell, asking Alfredo to give

her image—daguerrotype?—to his future

virgin bride, whose arms, hypotheses, are pure—

take this picture and tell your girlfriend

I’m now an angel watching you in heaven. . . .

I fell asleep promising that when I rose

I’d write a poem that did elaborate justice

to this world, but instead, in my Roman

slumber, Sophia Loren, Marcello Mastroianni

and Fellini visited and refused

to say what new film they were working on.

I begged, “Tell me before you spill it to the press.”

Sophia was singing Aida at the Met

and Colette hogged the parterre toilet—

none of the nobility waiting in line had a chance

to urinate before the Surgeon General

sent the fire curtain down on the Nile scene.

I am not a fake. I have two friends, three

or four children, five fathers, and a host

of tropical fish. A copycat, I photograph Tommy,

my first grade friend, who moved on Chanukah—

depressed pink light crimping the horizon’s skirt,

God mimicking Schiaparelli:

when I visited his new abode, nothing was the same,

the rooftop swept the sun

into green hatchets, and his house abutted on a marsh

which I never had the good fortune to fall into

else I’d now be giving you something keener than this sordid

compromise between deceit and grief. At last

I have a playmate to rival that original, and plenty

of cultural references thrown in, five-

spice powder, a predilection for the long walk, long

haul, not much fuss, closure

kept to a minimum, and hyperbole reigning

in her usual kimono, the color of merlot—

the silk one hanging in my closet smells awful,

I’ll never go to that cheap tailor again

(she charged only seven bucks for intricate repairs).

Walking along the Hudson in 1977

beside an imaginary Balanchine troupe’s prima

ballerina, I saw, on the pier,

a man with top Levi’s button opened

showing groin hair, and I thought,

“Ditch the ballerina and follow this mariner toward his deeps.”

I didn’t inspect his belly’s superscript

or footnotes, nor the tattoo, serving notice

like Madame Defarge, nor did I value,

at half her worth, the dancer, her navel bearing

superior complexity, if I’d known how to see it.

I dreamt a great poet drove me to Philadelphia.

Her mother disapproved of my defection

from orthodox practices, and I persuaded her that tapioca

was a good idea for a dinner party; then my mother

walked onstage without warning during a poetry reading

I was trying to give, and she said, “I’m sorry I’m late,

this is not normal behavior, but I have urgent errands.”

I am dreaming of a blue notebook

that admits every atmospheric tic, the despicable

difference between haute and bas,

the small talk of my umpteen loves, my hand

opening the window to invite

warm rain, and sunset rouging the street

my father’s uncle trudges up to bring a box of See’s

chocolates on Christmas day—the uncle who, by marrying

a Catholic, survived Germany,

then moved to California to sort and deliver mail and give me,

for high-school graduation, one thousand envelopes

engraved with my name and the wrong return address:

I disgrace the family by mentioning

graves and emptiness

without also describing the accompanying

ameliorating handkerchiefs

and armchairs, philosophy lessons

and the Rubinstein concert in Caracas—”You have no irony,”

my friend says, whose scarves are orchestral,

and I reply, “I have no sincerity.” I used to weep

after every haircut, smothered by uncertainty—

which look did I want, butch or meandering?

“D’ja know?” is my new expression,

unconscious homage to Djuna Barnes—do you know

what I mean, do you know what I seek, do you know

that duration has not redistributed its fathoms since our last

supper, and do you greet the sky’s openness

to opium as if its saturnalian curriculum

made you and me

the sole descendants of the Ballets Russes?

Before quitting

(accept this photograph, dear, and know

that an angel gazes down on your happiness)

promise that you will not destroy the magic net

the marooned December moon

casts over casual thought; promise you will give moments

on odd afternoons for such pleasure

as a photograph affords—I’m thinking of the Rudy Burkhardt shot

of a solitary Brooklyn studio, its few, faint

artifacts fastidiously arranged on a table—a room

that might have been my mother’s, had her childhood

looked out to the Bridge rather than to my own parched future birth,

and had she worn clean oxfords in the old photo

I kept on my dormitory wall (her face pushes

against her brother’s chest, and the light’s unkind)

beside an index card bearing a typed Pound quote

about the immorality of not staring the subject

straight in the eye, or else about Gaudier-Brzeska’s death

in the Great War—

had she worn not unlaced boots but clean smackers,

a kind of giggly shoe

that John Bunny, best fat comedian of the silent screen,

might have longed for,

were he to lose the girth that made him famous;

and promise I will not curtail

memory’s melisma into the gaudy carnival

float shapes I have been pursuing for too many years—

Prendi, quest’è l’immagine de’ miei passati giorni—

squandered days in a whirling cyclone downstream,

who dares capture or call you home before the figure, nude

on the silver plate that oversees these lines,

raises his hand to feel the fine light fail?

*

Image via The Red List: Lynes, George Platt. Detail of “Skeletons (Jared French).” 1947.