“Letter in the New Year,” by Donald Hall, appeared in the Summer 1997 issue of Michigan Quarterly Review.

*

to Jane Kenyon

New Year’s Eve I babysat

the girls in Concord, napping

on the sofa. In Seattle

last year we slept through

as usual, except that your sugar

went crazy from Prednisone.

I pricked your finger

every four hours all night

and shot insulin.

The year

of your death was not usual

and this new year is offensive

because it will not contain you.

For six months Gus flung himself

down in the parlor all day,

sighing enormous sighs.

Now he lies beside me

where I sit in my blue chair

eating bagels in the morning,

watching basketball by night,

or beside our black-and-gold bed

where I read and sleep.

Ada curls on my other side.

I’m what they’ve got;

they know it.

Stepping outside,

I check the weather to tell you:

The sun is invisible, still

ascending behind Ragged,

but west of the pond, its rays

pass overhead to light

the snow on Eagle’s Nest.

The moon blanches in a clear sky,

with one cloud scudding

to the south over Kearsarge

which turns lavender at dawn.

Time for the desk again.

I tell Gus, “Poetryman

is suiting up!”

The bulletin

this January is snow.

New Canada is a “One Lane Road”

along the old pasture’s woodlot.

The hills collapse together

in whiteness squared out

by stone walls that contain

wavery birches and boulders

softened into breasts. White

yards and acres of snowfield

reflect the full moon,

and at noontime the sky

turns its deepest blue

of the year. I puff as Gussie

and I walk over packed snow

at zero, my heart quick

with joy in the visible world.

Do you remember our first

January at Eagle Pond,

the coldest in a century?

It dropped to thirty-eight below—

with no furnace, no storm

windows or insulation.

We sat reading or writing

in our two big chairs, either

side of the Glenwood,

and made love on the floor

with the stove open and roaring.

You were twenty-eight.

If someone had told us then

you would die in nineteen years,

would it have sounded

like almost enough time?

This month Philippa and her family

moved into a house they built

on wooded land in Bow.

Each girl has her own room.

I gave Abigail a bookcase

and Allison a grown-up oak desk.

As I read them story books

on the sofa, I thought of you

making clothespin dolls

with Allison, to put on a show;

you were supporting actress.

When you were dying, you fretted:

“What will become of Perkins?”

The children telephone each morning

and our friends look after me:

I meet Galway and Bobbie for supper

in Norwich; Bobbie consoles me,

wearing your Christmas

cashmere sweats. Liam and Tree

bounce and exaggerate

the way we four did together.

When Alice took Amtrak

and Concord Trailways to visit

before Christmas, we watched

the Sunday School pageant.

Sometimes I weep for an hour

twisted in the fetal position

as you did in depression.

Hypochondriac, I fret over Gus

and decide he’s got diabetes.

In daydream I spend afternoons

digging around your peonies

to feed them my grandfather’s

fifty-year-old cow manure.

Next week maybe I’ll menstruate.

I want to hear you laugh again,

your throaty whoop. Every day

I imagine you widowed

in this house of purposeful quiet.

You would have confided in Gus

and reproached Ada, lunched

with friends in New London,

climbed Kearsarge, wept,

written poems, and lay unmoving,

eyes open, in bed all morning.

You would have found

a lover, but not right away.

“The sexual intercourse

of angels,” Yeats

in old age wrote his old love,

“is a conflagration

of the whole being.”

*

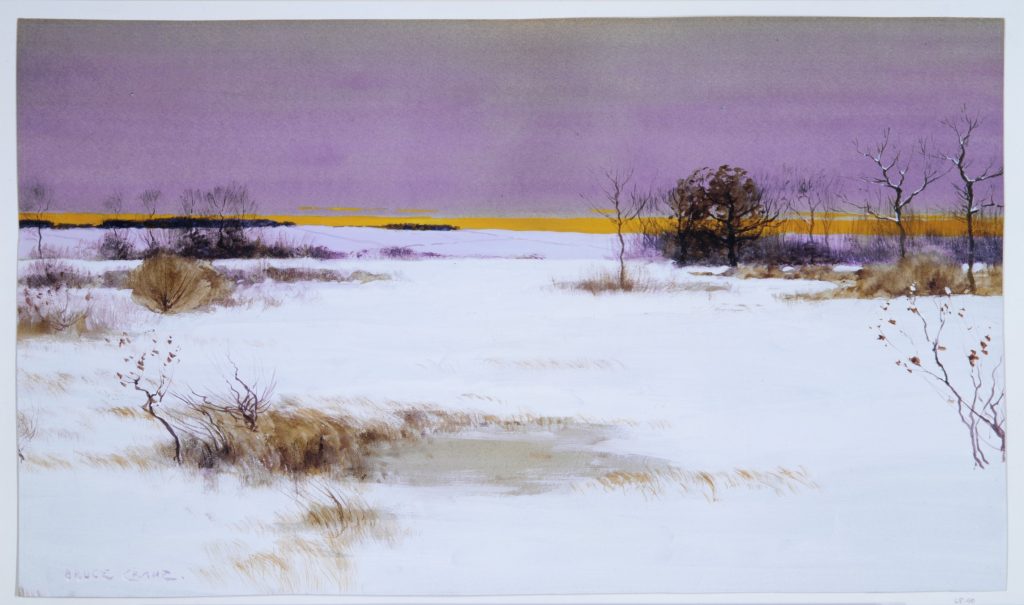

Image: Crane, Bruce. “Snow Scene.” Watercolor and gouache on blue-gray wove paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.