“Once upon a time there lived a bird and then that bird stopped living.”

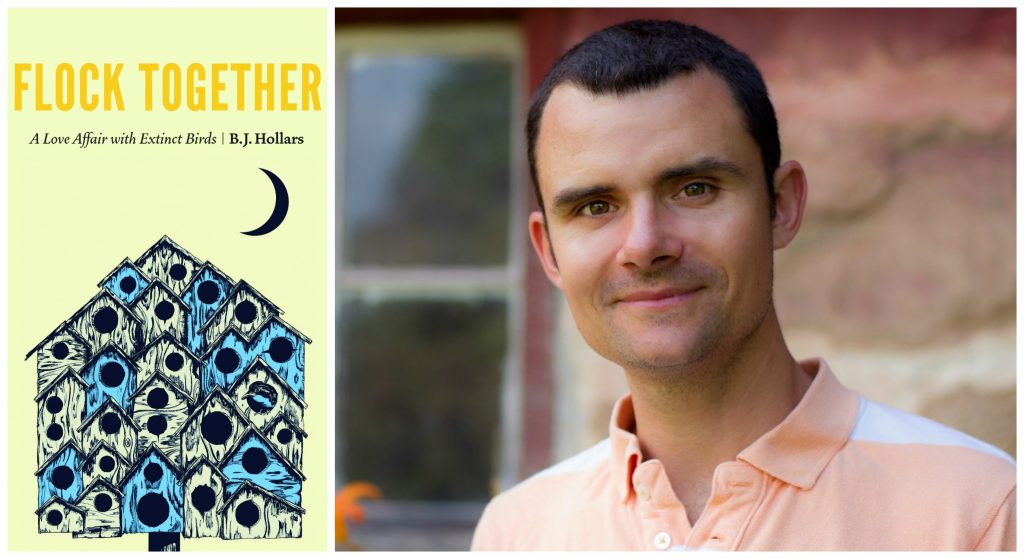

So begins the opening chapter of B.J. Hollars’s latest project, Flock Together: A Love Affair with Extinct Birds, a work that examines vanished North American species and asks why certain ones — particularly groups that have managed to thrive so vibrantly on film — have not been able to flourish in life.

Hollars is nothing if not a man who likes to find things. Old things, obscure things — whether it’s passion, pastime, or cerebral fetish, it makes for a captivating brand of storytelling. And while the book tells the stories of individual species such as the Dodo, the Passenger Pigeon, and the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, it also delves into the lives of birders, conservationists, and even bird-slayers, the work of whom can be found in archives and museums today. In the book’s titular essay, Hollars and a friend strike out into the wilds of Wisconsin to uncover the lost homestead of the hermit Francis Zirrer, a man known in ornithology circles as the naturalist who first provided evidence of the Northern Goshawk in Wisconsin. “We tromp the trails before ducking into the wilder regions,” Hollars writes, “our eyes scanning the ground for any sign of Zirrer’s cabin — a foundation, perhaps, or a few old boards…. As we cut through the brush, I can’t help but feel as if we’re being watched. Not by humans, but by the many animals sitting in silent observation.”

Hollars likewise journeys into the back rooms and locked drawers of museums housing egg collections and taxidermied marvels. In the bird collection room at the Field Museum in Chicago, in the presence of a colorful Roseate Spoonbill and a Carolina Parakeet, he’s given the rare chance to hold — with gloved hands — the long-dead body of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker. “Holding that bird,” he writes, “I’m faced with a complicated feeling — part joy, part grief, part something bordering on the sublime. And it’s my inability to give it a proper name that makes the emotion even more powerful. This is my moment of quiet reckoning, my real-life anagnorisis.”

In addition to Flock Together, Hollars is the author of six books, most recently, From the Mouths of Dogs: What Our Pets Teach Us About Life, Death, and Being Human, and This Is Only a Test. His essays and short fiction have appeared in many journals and magazines, among them North American Review, Passages North, The Rumpus, and TriQuarterly. He is a former contributor to the MQR Blog, where he penned the Unsolved Histories series. Hollars serves as a mentor for Creative Nonfiction and is the reviews editor for Pleiades. He is an assistant professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire.

I had the pleasure of corresponding with Hollars via email about writing, the creative process, and what extinct creature he’d pluck from the past, if able.

Let’s warm up with something basic. How did the essays in Flock Together come about, and at one point did you realize you were working toward a collection?

You know, I admit I hadn’t really thought of it as a collection. To my mind it’s long-form nonfiction, a book consisting of three strands that cycle through. You’ve got your Ivory-billed Woodpecker strand, your hermit-in-the-woods strand, and my own “becoming a birder” strand. I suppose rather than thinking of them as essays, I always sort of visualized these repeating sections as strands of the same story; strands that, if pulled in the right directions, ideally provide readers a deeper understanding of the connection between birds and humans.

I suppose I realized I was working toward a book when I asked myself, How close can you get to an extinct bird? And then, I set out to try. My journey of combing through museums and specimen drawers was what ultimately spurred the longer narrative. Once I held an extinct bird skin in my hands, I knew I had to start sounding some alarms about our own environmental crises. And the best way I could do that, I figured, was through stories.

Plenty of research and field work goes into your writing. In terms of this collection, what was your most memorable research moment?

Plenty of research and field work goes into your writing. In terms of this collection, what was your most memorable research moment?

There’s a moment in the book when I recount stumbling upon the last known sketches of the last confirmed American Ivory-billed Woodpecker. I was chatting with a curator of a regional art museum when she mentioned having the papers belonging to wildlife artist Don Eckelberry. Of course, in Ivory-billed Woodpecker circles, Eckelberry is well known. In 1944, the twenty-three-year-old was dispatched to a Louisiana swamp to sketch the last Ivorybill in her tree. For two weeks he sketched her, trying to preserve in his sketchbook what we’d failed to preserve in real life.

When I held his sketches in my hand—the last sketches of a species, mind you — my heart shattered. How, I wondered, had we let it come to this? The sketches were beautiful, of course, but I wasn’t satisfied. What I would have preferred is the continuation of the species. These days, most people agree that all we have of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker are study skins, photos, sketches, and a recording of her call. Well, all of that, as well as a powerful cautionary tale.

I noticed in reading “The Hermit and the Hawk” that it greatly differed from its original version on The Rumpus in December of last year. Can you speak a bit to the process of retooling published pieces to fit the structure of a book-length work?

In that case, it actually went in the opposite direction. The book chapter was already complete before I scaled it back to make it work for the online medium. But yes, you’re right, the final version is quite different. There are a lot of reasons for that. The most interesting, however, has to do with my personal grappling of what happened between the aforementioned hermit and hawk in that woods nearly eighty years ago. It’s a long story, but the short version is this: one day the hermit killed a rare goshawk to send as a gift to his friend. What’s less clear is why he did it. As far removed from the scene as we are, it’s hard to provide motive. And even when browsing through the hermit’s letters, we’re only left with so many clues. The versions are different, mostly, because I struggled to pin down the facts. And so, while the online version and the book version are factually similar, the way I present those facts are quite different. When writing about an historical event — even one as seemingly modest as this — presentation is everything. I’m always asking myself how best to convey information to readers: via scene, via quotation, via exposition, etc. I’m not sure there’s any right way to do it. I think it has to do with proportion, tone, and one’s audience.

Who gets to see your drafts, and what’s your revision process like? Does it differ much for fiction vs. nonfiction?

Who gets to see my drafts? Very unlucky people.

I kid, of course. The truth is, those “very unlucky people” are actually my friends, and for reasons beyond my understanding, time and again they’ve weeded through my knotted messes and helped me find ways to write the most reader-friendly narrative I can.

I’m the first to admit that reading about history is rarely as exciting as reading a great novel. And reading about the history of extinct birds is even less exciting for most folks. Which is why I really worked to find ways to tell this story in the most engaging way possible. And it’s also why I play a role in the narrative. I want to serve as a guide for general audiences. After all, I’m a budding birder myself, and relatively new to the birding world. But just because I wasn’t born a birder doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate everything that birds teach us, including their most poignant lesson of all: what our lives might be like without them. I want a general audience to feel this way, too — that the fates of birds matter to all of us. Because they do; we are linked. When we speak about the proverbial “canary in the coal mine” we’re harkening back to a time when miners used canaries to test the safety of a mine’s air quality. These days, though, all birds serve as a canary of sorts — they all give us a warning for our future.

As for the specifics of revision, I suppose nonfiction and fiction aren’t terribly different for me. The main difference, of course, is that in nonfiction I’m always grappling with the truth. And writing “truth” isn’t always reader-friendly. Fiction — though complicated for its own reasons — can be wonderfully liberating when it comes to facts. Yet with nonfiction I’m constantly negotiating the facts. Not watering them down, but trying to find ways to utilize them to their greatest effect. I’m always asking myself, “Which of these perspectives is the right one? Which version is definitive? And what do I believe in my heart, is true?” To some extent, being a nonfiction writer makes you a curator, too: you’re just trying to curate a story so someone else might know it.

I keep thinking of this fellow from the book, Charles B. Cory, the man who acquired and hoarded some 19,000 bird specimens before donating them to the Field Museum in 1893. Of the major and minor characters presented in Flock Together, what birding figure looms largest in your mind?

Cory is incredible. So many of the folks I learned about are incredible. They’re complicated, too, as are their ethics. (See: Charles B. Cory who, as you noted, killed 19,000 birds.)

I suppose the man who interests me most is Francis Zirrer. Here’s a guy who literally spent the majority of his life deep in the wilds of Wisconsin — observing nature and writing about it in a manner few others ever had. He had a front row seat to the magic of nature, after all, and he shared what he saw in his writing. There’s not too much of it left, mind you — just a handful of articles — but also, several letters to his friend. And its these letters that really fascinate me. They confirm his loneliness, his frustration with the world, and his endless love for the creatures that lived in the wilderness that surrounded him. This is a guy who chose to live off the grid, who traded in the niceties of twentieth-century life to subsist in the wilderness. And he was rewarded for it by the things he saw. Today, well over half a century after his death, we’re rewarded for his sacrifice, too. His gift is the words he left behind.

If this is a book with a conservation message — and I hope it is — then Zirrer offers the most important lesson of all: we only care about things when they matter to us. And they matter to us most when we’re close.

Can you speak to your influences as a writer? Would also love to know what sort of books you grew up reading–it’s clear from your work that you have a penchant for the mysterious and arcane.

I grew up in the library stacks, mostly around the shelves that housed the books on Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster. Which I suppose is my way of saying that I’ve always been fascinated by the strange. Not that birds in and of themselves are strange, but the idea that they can vanish forever is strange, or at least was strange to me in my youth. When I wasn’t busy with Bigfoot, I was fascinated by the dodo bird. How, I wondered, could a once-living species of bird be nowhere on the planet? And how could we even know that for sure?

As I describe in the book, I dedicated more than a few afternoons throughout my elementary school years to searching my backyard for that particular bird. And I never found him. I never found a single dodo. And I suppose that’s what initially spurred my concern for the environment all those years ago: the notion that the creatures we don’t take care of will ultimately leave us.

But in addition to birds going away, so, too can their stories. I’m no scientist, nor conservationist, and thus I’m in a less-than-ideal position to save the birds we keep losing. What I can save, I hope, are their stories, as well as the stories of the people who tried to save these birds in their own lifetime. On the darkest days, when I learned of some new tragic end to a species of bird, I’d ask myself what good my words might do. To be candid, they probably won’t do a lot of good. Certainly not enough. But I always hoped that if I could introduce readers to these lost birds and people, then maybe readers might begin to take notice of what we we’ve lost and keep losing. And if I can persuade people to take notice, then perhaps they’ll take action, too.

What books are on your list to read in the near future?

I’m currently in the throes of a new project related to the Freedom Riders, so most of my reading centers around that. I’m all tangled up in microfilm and archival papers, and I’m loving every second of it.

But beyond the research reading, I’m also excited to read Laurence Leamer’s The Lynching. His book discusses the courtroom drama that took down the Klan, as well as the murder of a 19-year-old African American named Michael Donald, whose death spurred the drama to come. My first book, Thirteen Loops, is also about Michael Donald. I can’t wait to learn more about the young man who I spent so much time trying to know long after his death. This is probably what I love most about being a writer: the chance to enter into a conversation, offer something, and then stick around to hear a whole lot more.

Final question: You’ve just been bestowed with the power to bring any extinct animal back to life for a day. Forget what benefits science; this is a creature you want to stare at. What do you pick?

A creature I want to stare it, eh? Well, all of them, of course! This is precisely the kind of question that kept me up at night throughout all those years of my youth spent browsing the library stacks.

Oh dear … well, after six hours of mulling over this question I’ll have to go with the Megatherium, better known as the ground sloth. But not just any old ground sloth … we’re talking elephant-sized!

Oh dear … well, after six hours of mulling over this question I’ll have to go with the Megatherium, better known as the ground sloth. But not just any old ground sloth … we’re talking elephant-sized!

There’s an interesting side story about a group of nineteenth-century naturalists and scientists who founded what they dubbed the Megatherium Club — sort of a scholarly adventurers’ club of sorts. Apparently, when they weren’t out on expedition, they lived in the Smithsonian Castle. Can you imagine that? Living in the Smithsonian? I wrote a piece about it once. But here I go again … starting with an extinct animal and ending with stories of people now long gone …

All these stories are important, of course. And whether you have a mouth or a beak, we should listen to you.

Flock Together: A Love Affair with Extinct Birds is forthcoming from the University of Nebraska Press in 2017. To find out more about Hollars and his upcoming projects, visit bjhollars.com.