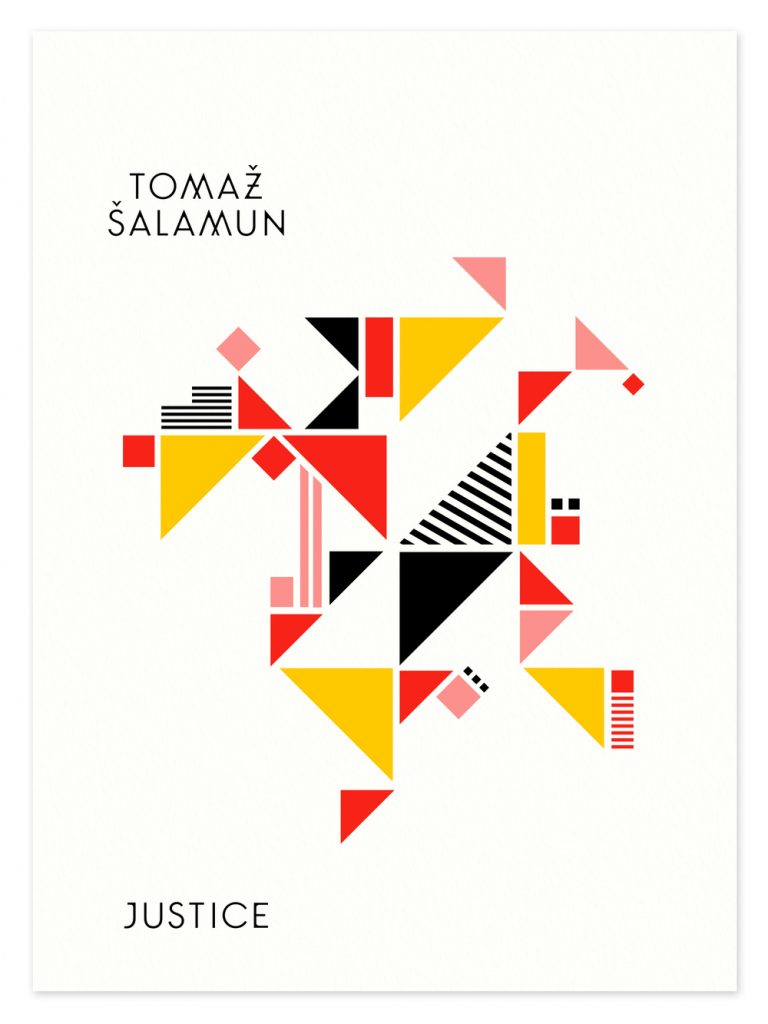

It is a thrilling thing, for many of us, to consider a new book by Tomaž Šalamun. Now, nearly an exact year after Šalamun’s death, we have Justice, the first posthumous work. It is Šalamun at his very best, full of energy, always after different approaches, exploding his vision into a celestial pantheon of different realities. A few months ago in these pages I shared some thoughts, and, especially, favorite lines of Šalamun’s past works. This month I had the pleasure of chatting with Šalamun’s translator and collaborator, poet Michael Thomas Taren, about this first posthumous collection, working with Šalamun, and the unique endeavor of translation as a creative enterprise. His effervescent illuminations offer the perfect precursor to the new poems, available soon from Black Ocean.

*

I’m really interested in the source of these poems, especially the timeframe in which they were written. Are they all from the past few years, or do they span a longer range? I wonder if these works indicate anything about Šalamun’s trajectory?

These poems were conceived all over time. I don’t know when the oldest are from, but I do know that the poems written in couplets, the cloven sonnets, I shall say, are from the past fifteen years. It’s impossible to date them all. They are several centuries old. Some are not older than an Ibis embryo. I’d put the range then between Christ’s birth and the latest Ibis embryo. Some are from the 70s.

What I mean to say is–I’m really interested in the effect that the highly positive American reception of Šalamun may have had on his work. I want to say it compelled him into an even higher actualization, greater exuberance, greater pushing of imagistic and mental boundaries. I wonder if you might say anything about that, if that’s accurate. I’m curious how his legacy might be different in Europe and the US?

This is to say that Tomaž’s exuberance was always off the handle. He always thought his legacy would be found in America. America grafted onto his encyclopedia of references. He loved to write in Starbucks, especially that of Union Square. He bought Starbucks every day when he was in America and brooked no criticism of that company. Tomaž liked America quite a lot. At either periphery of the Atlantic he’s viewed as something childlike and mystical. In his home country it’s a split between reverence and annoyance. He became both a trophy case and Modernity’s whipping boy.

Are these all poems that didn’t fit in other collections, or are they fragments from unpublished whole works (the section headers seem to suggest this)? Maybe, can you talk a little bit about the process of hunting out and choosing these poems, maybe likewise ordering them?

We made up the sections because neither of us could summon much effusiveness for the dressing of past carcasses (i.e. a paean to discrete chronology, i.e. the reasonable selection method involving the Persian carpet and the stack of pages before my hand dropped them). Tomaž didn’t witness me writhe on that aluminescent imbrication. He felt I should be alone.

The process was necessary because the poems came from so many different collections and from the seven years of our collaboration. There were so many poems. I would have wept from the tedium of tacking them together using an artful logic. There was also a primitive score chart involved which determined who would advance to the writhing round.

Šalamun has a reputation, I think, of working really collaboratively with his translators—can you talk a little bit about this process, even just the logistics of how the translations were carried out? Of course I’m also interested in anything artistically notable about the translations—are there particular conventions or traditions that you worked against, or were careful to preserve, things like that. Are there noteworthy difficulties or joys in translating from Slovenian in particular, or certainly translating challenging or “experimental” poetry? The translations (as an English-only reader of course) are absolutely fabulous: contemporary, energized; I want to say that this is more than your usual translation (whatever “usual” might mean).

We were like two very affable beasts licking an enormous ice cream cone until it resembled the poem. We sat at cafes, preferably on the terrace if the weather allowed. We drank coffees and talked through the poems. Talked words into them and words out of them. I don’t remember there ever being any difficulty. Tomaž had a wariness of the thesaurus while I was a vigorous proponent. He warned against too much thesaurus enthusiasm. Those days on the terrace were the most assuring of my life. I hope that this feeling seeped into the translations.

This is a hard question, partly because I don’t know what I mean, but this is the first posthumous work, and I wonder if it’s appropriate for us to approach it as a memorial. There are elements that are certainly funereal, or concerned with legacy, but these could easily be brought into greater than actual relief given his recent passing and the kinds of things we ask from posthumous works.

There is no memorial, I think. The only memorial to Tomaž will be when reading ends forever and people live as angels with memories like a long sock that keeps elongating as a dog rushes around with the ankle of it in his mouth. Tomaž’s poems are always making little passes at death, multivalent scatterings of romance and finger waggling and sarcasm. On the other hand, his metaphysics was deeply polyamorous.

Maybe the memorial, if it resides in a book, will be when a devoted someone will take on the Herculean task of translating Tomaz’s collected works into English, for those will be volumes which weigh as marble slabs.

Please tell us there are more poems that will be coming to light, further collections down the road. Are there new translations you are working on?

There’s a deep digital well filled with lots of poems. Five hundred or so. A book must emerge.

*

Michael Thomas Taren Lord Kreiden is a world deformed, bludgeoning, heavy and livid. He is the author of eunuchs (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2015). He is co-translator with Purdey Lord Kreiden Thomas Taren of Tony Duvert’s Atlantic Island (Semiotext(e), Fall 2015), Mated, by Joris-Karl Huysmans (Wakefield Press, Fall 2016), and Dust Pink by Jean-Jacques Schuhl (Semiotext(e), forthcoming). They are currently working on a free verse translation of the complete poems of Leconte de Lisle.

Tomaž Šalamun was born in 1941 in Zagreb, Croatia and raised in Koper, Slovenia. He published more than fifty books of poetry in Slovenian during his lifetime, and he is not only recognized as a leading figure of the Slovenian poetic avant-garde but is also considered one of the leading contemporary poets of Central Europe. In 1996, he became the Slovenian Cultural Attaché in New York and lived in the US intermittently until his death in 2014. His honors include the Preseren Fund Prize, the Jenko Prize, Laurel Wreath, Poetry and People Prize, Njegoš Prize, Europäsche Prize, Pushcart Prize, a visiting Fulbright to Columbia University, and a fellowship to the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Besides teaching at several distinguished universities and having his work appear in over seventy journals and magazines internationally, he has had fifteen collections of poems published in English so far. All together, his poetry has been translated into over twenty languages around the world, numbering over eighty volumes.

Tomaž Šalamun was born in 1941 in Zagreb, Croatia and raised in Koper, Slovenia. He published more than fifty books of poetry in Slovenian during his lifetime, and he is not only recognized as a leading figure of the Slovenian poetic avant-garde but is also considered one of the leading contemporary poets of Central Europe. In 1996, he became the Slovenian Cultural Attaché in New York and lived in the US intermittently until his death in 2014. His honors include the Preseren Fund Prize, the Jenko Prize, Laurel Wreath, Poetry and People Prize, Njegoš Prize, Europäsche Prize, Pushcart Prize, a visiting Fulbright to Columbia University, and a fellowship to the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Besides teaching at several distinguished universities and having his work appear in over seventy journals and magazines internationally, he has had fifteen collections of poems published in English so far. All together, his poetry has been translated into over twenty languages around the world, numbering over eighty volumes.