Chidelia Edochie’s story, “The King of Hispaniola,” first appeared in Michigan Quarterly Review‘s Winter 2012 issue.

I spent that Christmas Eve with my schoolmate Bibi and her parents at the National Palace, comparing the sizes of presents and our thirteen-year-old breasts with the other daughters of cabinet members and businessmen. All over Port-au-Prince younger children were taking off their shoes and filling them with hay so that Papa Noël could lade them with gifts as they slept. In the palace chandeliers gleamed down on us, everyone so drunk off of anisette punch that the whole place smelled of sugar and rum and salt from their sweat.

Bibi’s father, Mr. Mesadieu, kept an arm around President Duvalier as if they were brothers. The whole country called him Baby Doc—not fondly—and I’d heard Mr. Mesadieu refer to him as le bébé idiot. Our textbooks said that the Duvalier family had been the savior of Haiti, though our teacher often let it slip that he found the extravagance of their lifestyle distasteful. But I knew that Bibi liked him. She didn’t say it, but I figured it was the president’s soft-faced reticence that contrasted so sharply with her own father’s aggressive conceit. Her family was part of the tiny Haitian elite, most of them with so much French and Spanish blood that their skin had been diluted to the palest shades of brown, no kink in their hair. Their group controlled much of the Duvalier administration and often controlled Duvalier himself. Mr. Mesadieu and the other men had clasped the president in a rocking embrace and were singing old Haitian Revolution songs. They fumbled with the Kreyòl, far more used to speaking in French. Mrs. Mesadieu sat across the room with the other women, all dressed in bright Yves Saint Laurent gowns, amused by their men.

The party did not last long. Before midnight a group of protesters, woulos, surrounded the iron gates of the palace to lambast the President over the cost of food. They shouted for Duvalier to come out and face them. They chucked burning sacks of rancid goat meat onto the acres of green lawn. Bibi and I watched from the tall windows, straining our eyes to distinguish the dark faces from the night.

“Check out this show, Alíse,” Bibi breathed into my ear. “If you’d stayed home with your mama, all you’d have gotten was a few fireworks outside a church.”

Bibi was only half right. My mother was a low-level nurse who’d recently acquired a religious zeal, and she’d have certainly made me attend midnight mass. The church she liked was in the poorest part of our neighborhood, Carrefour, where one-room concrete houses sat atop each other like gray, ascending plateaus. At this church there would have been more than the usual Christmas fireworks. There was a new priest—a dark, bulgy-eyed man who in his sermons encouraged the people to reject the regime and starvation in favor of revolution and food. I took my face away from the window. These men might have been from my mama’s congregation.

We left soon after in Mr. Mesadieu’s armored car. As we moved slowly up the driveway Bibi and I turned in our seats for a final look at the palace—a massive structure of ivory-painted concrete and beveled domes, all lit up. Mrs. Mesadieu sat nervously in the front seat as we inched toward the protesting men. Her skin was the same copper shade as Bibi’s, and they had the same face—pudgy cheeks and large sunken eyes like dolls. Mrs. Mesadieu clutched her hands in her lap, then flapped her elbows to air out her armpits so that sweat rings would not stain her gown. She turned around in her seat and smiled.

“Didn’t we have a wonderful time, girls?” she said to us as the car reached the gate where the protesters still stood. “And Alíse, your first time at the palace, what’d you think?” She turned to her husband. “And did you get a look at Michelle Duvalier’s gown? How could she even move, all those jewels.”

“Le bébé should have had them shot,” said Mr. Mesadieu, slowing the car for a better look at the woulos. The men stood rigidly in work shirts unbuttoned down to their crusty navels, their arms wrapped around the gate. The police had arrived, but were only sitting in their cars beaming their headlights on the men. Letting them feel exposed, daring them to flee. “They want food?” said Bibi’s father. “Feed them a bullet.”

Beside me Bibi clutched my arm and said, “But it’s Christmas.”

And now here we are, twenty-five years later, sitting across from each other in a street café in Atlanta. I didn’t know who she was at first, just watched as she wound her way through pedestrians, a woman close to forty making the heads of young homeless men turn as she passed. I almost started to draw her. Then with a shock I recognized Bibi, briefly mistook her for her mother. I was too scared to turn my head, thought if I moved even an inch she would notice me. Then she did. She saw me sitting at my little round table, sketch papers held down by a mug, my eyes squinting in the sun, and squealed out my name. “Alíse!”

“I’m not surprised to find you in Atlanta,” Bibi says, after giving me the chance to squeal back and hug and she’d settled into a chair and ordered a lemonade. “Miami probably isn’t intellectual enough for you. And New York, oh my god, everything’s so political. And church-y.”

She stops talking when her drink arrives, but only for a second, to sip. The waiter—an olive-skinned man with slightly bucked teeth—trips over the large purse that Bibi has laid on the floor. She tosses her head at the disruption, then answers a question I wasn’t going to ask.

“I just tell people I’m from France,” says Bibi. “I won’t even mention Haiti. How can you stand it? All that pity.”

I understand her completely. I’ve been showing my paintings in small galleries on both coasts for over a decade, but in the past year I suddenly gained the kind of recognition that for most artists is only possible after death. The ground shook a thousand miles away—tragic, yes, but I wasn’t there—and since then I’ve been invited to sit on dozens of panels on disaster art. Schools were offering me long-term lectureships. Last month an important reviewer wrote an article about me in Art Today, calling my smiling grayscale self-portraits “ironic representations of the loss of a nation.” No one knew they’d been painted almost ten years before the quake.

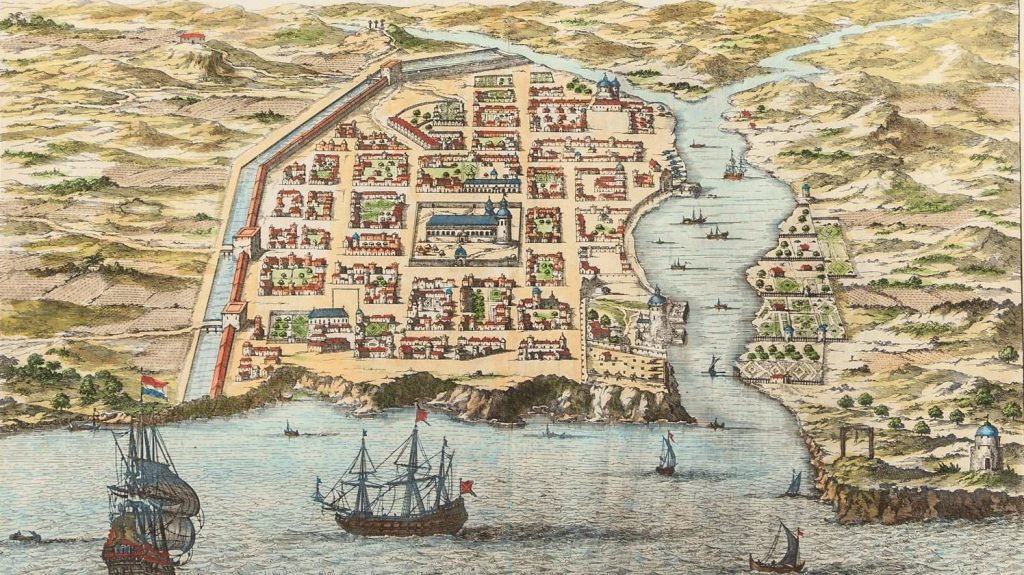

I remember the photo shoot for the article, the photographer from the magazine visiting my studio. Usually it is considered inauthentic, promotional, for a magazine to feature the artist rather than the art. But they felt an exception could be made with me, given the recent events. The photographer positioned me before my biggest painting, called King of Hispaniola, a portrait of myself in blue and gray hues grinning maniacally. The shot they used for the magazine cover was one where the photographer had positioned me on my knees, my back to the painting, staring out a paneless window into a gray sky. The caption that ran with the cover said “The King is Dead: Haitian Art Now.”

“Oooh, and I saw your cover,” Bibi is saying, at the same time pointing at my danish and eyeing the waiter. “That art magazine thing. But did you have to look so sad?”

At all of this—her impeccable ability to read my mind, my discomfort at being appreciated by critics, the absurdity of danish—I have to laugh. And then I cannot stop. I try to hold it in my throat, biting my lip. My body shakes the table. Bibi has to pick up her drink to keep it from sloshing.

She narrows her eyes, unsure, maybe, of how to take me. But I don’t stop, and then she starts. Her laughter lilts, mixing with my deeper chuckle. We lean into each other, our heads almost touching over the table. Then we lean back into our seats, and then toward each other again. People standing in line at the counter turn and stare at us, and those sitting nearest shift their bodies away. We don’t care. We go on that way for a few seconds. Finally we both sigh, ending it.

Bibi releases a loud, breathy “Mon Dieu,” telling the whole café that we aren’t simply two middle-aged black women causing a ruckus in the middle of a restaurant. We are French. And it is as if nothing had ever happened until this. Because here we are: in America, sipping cold drinks on a warm day, pretending to have forgotten all that came before.

The Mesadieu family lived in Pétionville, a rich suburb of Port-au-Prince where large pastel homes sat among the hills of the Massif de la Selle. Theirs was a pink-bricked mansion surrounded by a gate. Stone statues of Loa gods flanked the driveway leading up to the house. Around back was a pool, emptied for the mild winter. Once we’d returned from the palace Bibi and I sat awake in her room, waiting for the sun.

“I hate my name,” Bibi was saying. “It sounds like a little girl. Don’t you think I should start going by ‘Blanchefleur?’”

Bibi’s mother had come upon the name—Blanchefleur—while studying Arthurian legend during university in Paris, and knew immediately that she would name her future daughter that. But when Bibi was born her father had just gotten the high-ranking position of Assistant Minister of Finance, and Duvalier’s father was still in power then, the first president to use noiriste politics to mobilize the black Haitian population against the small mulatto elite. Given this, it was not a good time to have a daughter called ‘White Flower.’ But Mrs. Mesadieu would not budge. So she and her husband compromised with a nickname, Bibi.

We stayed up for hours more as the Christmas fireworks went off in the distance for the reveillon. We chose Cuban singers as our husbands, talked about what it would feel like when we left home for university. I told Bibi that my mother wasn’t sure if we’d have enough money for a college in France, that I might have to do my first year locally, maybe in the Dominican Republic if I was lucky. Bibi looked disappointed, but not surprised.

“I better meet some other island girls there, then,” Bibi said. “Everyone knows French girls are snobby little bitches.”

The Mesadieu’s maid, Emerante, came into Bibi’s room carrying a suitcase. She walked over to Bibi and stroked her on the head. Emerante was from a family of pig farmers in Port-Salut, and had worked for the Mesadieus for so long and so intimately that, until Bibi was three years old, she took Emerante to be her mother. The maid had secretly fed Bibi mais moulu cornmeal—peasant food—behind Mrs. Mesadieu’s back, fattening her up. When Mrs. Mesadieu found out, she’d tried to fire Emerante, but Bibi had cried so hard and for so long that her mother had had no choice but to hire the old woman back. Bibi had told me the whole story one night after seeing her father, drunk, slap her mother.

With Bibi and I still lying on the bed, Emerante began packing the suitcase with Bibi’s clothes. Mrs. Mesadieu came in, still in her gown from the party. Her forehead was shiny with sweat and her lipstick had smeared a little down her chin.

“Your mama is at home, yes, Alíse, we can have you dropped off?” Mrs. Mesadieu said, glancing at me. “No, no,” she said to Emerante, rushing over and slapping at the old woman’s hands. “Don’t pack a swimsuit, this isn’t a vacation.”

Bibi and I had been lying with our arms and legs spread out, our heads touching. At her mother’s words we popped up, too quickly, got dizzy.

“Mama,” Bibi said, “what’s happened?” But Mrs. Mesadieu had already left the room.

Emerante explained to us in her thick Kreyòl: she had been the one to answer the phone. It was another maid calling from another mansion, closer to the city. The standoff between the protesters and police had continued. A protester had thrown a brick at one of the police vehicles, breaking the windshield, breaking the silence that had pervaded up until then. The police started to beat the men, not knowing that a block away, in the dark, waited hundreds more. In the end it was the policemen who’d had to beg for their lives. They struck a deal. Take their little revolution outside of the city, away from the palace, and the police would not try to stop them. The men had asked for weapons. But the police could not hand out guns, of course. So the men then requested machetes, and the police said that that could be arranged.

Now maids were making phone calls all over Port-au-Prince, some of the protesters were their own husbands and sons. They urged their employers to leave the city, to go deeper into the country. The richest families would be targeted, of course.

“Your papa says we’ll cross the border into le Republique Dominicaine,” says Emerante.

Bibi snorted. “See there?” she said to me. “Papa’s not worried at all. Thinks he can go wherever he wants, do whatever. Like he’s the putain king of Hispaniola.” She rolled the French curse on her tongue like a candy.

“Alíse,” Emerante said to me, “go downstairs now. A car waits to take you home.”

Until then Bibi had taken everything rather calmly, she and her family were used to the suddenness of peasant revolutions and quick escapes. But when I got up from the bed to go, she jumped up, too, gripped my arm.

“I can stay with her!” Bibi cried. Emerante did not even bother to respond, just kept packing. She stopped only to fish out a wafer from the pocket of her dress, chewed it calmly, waited for me to leave. She’d always treated me this way, knowing that my place in the Mesadieu house was only slightly above her own. My mother’s church had gathered the money to send me to the private school Bibi attended, and it was there that we met. Bibi had taken in my looks with a glance—my own skin lighter than hers by just a shade, pure luck—before allowing me into her world. Now, Emerante’s nonchalance toward me seemed to sooth her. It was enough to make Bibi release me and sink back into the soft down of her bed. “All right, see you when I get back,” she said.

Downstairs, I hurried across the vast, empty house, suddenly afraid the car would leave without me. In the foyer sat a large white stone sculpture of Veronique Lareine, a Frenchwoman who’d been a nurse and rumored to be mistress to Duvalier’s father before he became president. The sculpture was a nude, with Lareine’s pale buttocks facing outward and her face turned toward the wall.

“How many times,” said a voice behind me, “have you seen that statuette?”

It was Mr. Mesadieu. He crossed the foyer toward me in three long, quick steps. Though he walked with sureness I could see in his face that he was drunk, pale brown skin bloated red. He put his hand atop my head and let it rest there, like a priest giving a blessing.

“You could come with us,” he said softly. “Do you want to come with us? The beaches are so nice there, you can borrow a swimsuit.”

Small streams of sunlight were beginning to peek in through the high windows. But it felt too early for sun.

“Every time a few fishermen pick up some sticks,” said Mr. Mesadieu, “people run for the hills. They don’t know what a real revolution looks like.”

Machetes, I screamed in my head as he stroked my cheek. They’ve got machetes.

With one hand gripping my head, he moved the other quickly up my skirt. The same one I’d worn to the party, still stained with punch. My stomach twisted into knots as I remembered that I’d borrowed the skirt from Bibi.

“Papa!”

The cry came from somewhere above us, and it was her. I couldn’t make out her face, but her wail traveled down the stairs to my ears. I wrenched my head from Mr. Mesadieu’s grip as he turned around to face his daughter’s cry. I ran for the door.

Outside the sky was still gray. The rays of light I’d thought I’d seen indoors couldn’t have been real. I walked the long driveway to the road, where the driver—young and dark-skinned with a pink, droopy lip—squatted beside a truck, raking his finger through dirt. He stood when he saw me.

“Ki kote?” he asked. Where?

“Pote m’ lakay.” I said. Home…

Read more of Chidelia Edochie’s story, “The King of Hispaniola”, in our Archive.