In the Grimm tale we know, Hansel and Gretel come upon a gingerbread house in the forest, and hungry as they are, they eat. They eat, and the rest of the horror follows. Abandoned by their father, without a clear path to trace back home, they have no other option. Within the circuitous mysteries of fairy tales are familiar landmarks of humanity, most notably, survival. Survival, with its many faces, is present on nearly every page of Helen Oyeyemi’s novel Gingerbread. When Margot and young Harriet Lee cross state lines as cargo, Harriet’s hair turns grey, and her rich relatives on the other side pester her about it. When Perdita Lee comes upon a gingerbread recipe she believes will allow her to travel to her family’s origins, a place she cannot go in body, she eats. And the story unfurls in the horror (adventure? delight?) that follows. But Helen Oyeyemi’s latest masterpiece is not a fairy tale or a retelling. It’s many things with many names inside a body we call a book.

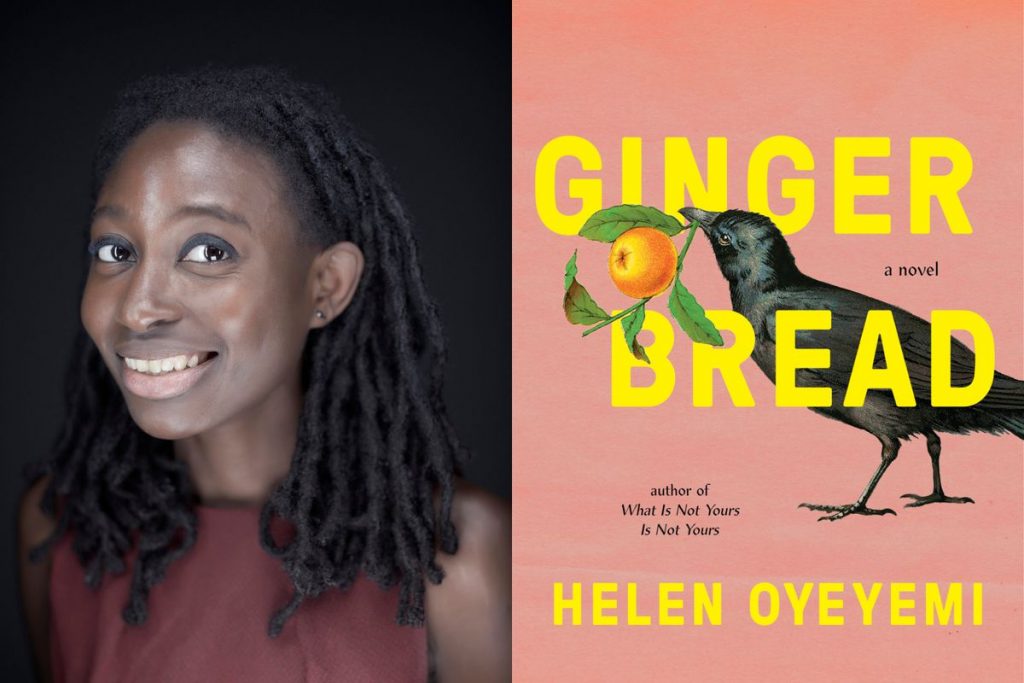

The latest of six novels (Oyeyemi is the author of six novels, one story collection, and two plays), Gingerbread follows the Lees—Margot, Harriet, and Perdita—and the people and places their lives touch. When we first enter the novel, we meet Harriet Lee, mother of Perdita Lee, and daughter of Margot Lee. An immigrant from Druhástrana, Harriet is a teacher in London, where she is a member of a parents’ association (the PPA). Of course Harriet holds multiple identities but for the beginning of this story, we know her as Harriet, mother of Perdita, daughter of Margo, maker and sharer of gingerbread. A family recipe formed in the deep of scarcity, in a time when marriage was “purifying,” the gingerbread “keeps and keeps,” resilience not unfamiliar to the Lee women.

Nothing in a Helen Oyeyemi story can be trusted, not mirrors, not money, not mothers. Still, the desire to trust—to love and to connect with those in our past, present, and future—is no less paramount. Throughout the rooms and houses and realms inside Gingerbread, nourishment remains vital to survival. But the passing down of recipes is the least of the magic (and not only because a recipe is not just a recipe). Here, daughters are “enigmatic minefields of classified information,” a mother ranks number one in a family list of “readability,” and the company of dolls makes a friendless girl seem “part of a clique of willowy teens with exactly the same shade of improbably perfect skin.” Here are rooms for outsiders and insiders and outsiders who think they are insiders. Here, nothing is provable and everything is true. There are haunted houses, houses escaping the market, and houses yearning for new life. There are meet cutes, doomed love, and delicious exchanges (sometimes bitter and dangerous, sometimes sweet, always refreshingly familiar) between mothers and daughters, family and friends. Oyeyemi builds a world so realistically full and complex that the reader is assured everything has a story, even a quiet, unassuming stone.

Allegory is not the (only) way to read a Helen Oyeyemi story, even if I resort to it every now and then, in my attempt to tell you about this novel. It does not help to question why an unfamiliar house or tree exists in Oyeyemi’s “forests” (at least not on the first read). If you ask why every unknown thing exists (e.g. talking dolls, a girl with two sets of pupils, a gingerbread house), you will be left behind. Note the first rule of an Oyeyemi book: there are many ways of seeing—nothing is more arrogant than trusting only one set of eyes. Oyeyemi’s narrators do not pander. Rather, they question why we must pander, why someone somewhere decided that one kind of person (or place) is more “real” than another. Narrative tourism is not her mission and neither is sentimentality. If anything, the voice is playful, full of surprise and wit, the unflinching tongue of a well-traveled philosopher who demands to know why you are not questioning the rules that govern you.

In the novel’s frame of stories inside stories, I was reminded of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights and Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night a Traveler. Reading Brontë and Calvino, I ask some of the same questions I do while reading Helen Oyeyemi’s Gingerbread. So while I am firm in my belief that Oyeyemi’s work resists categorization, I also found great pleasure in discovering how her work communicates with its predecessors in examining our world. Navigating the tenuous threads between reader and writer, character and place, home and stranger, these writers grapple with the (dense) pocket universes inside the “known,” the “official,” the “approved.” They drill deep into our comfortable assumptions to show us the hidden stories.

Gingerbread spans many realms—the national, sociopolitical, and mythical—to tell an inter-generational tale, revolving around the Lee women. If it had a shape, the novel would be a spiral, occasionally moonlighting as a circle, or a line. Sometimes Gingerbread is a (family) drama, a horror story, an immigration story. The novel certainly has fairy tales in it, as it does gingerbread and reminders of our present—Etsy, Amazon, Uber, social media, pop culture references. But a story, like a person, is more than one thing, so why do we make boxes? And no, the answer is not merely “to understand.” Oyeyemi proves that “understanding” transcends binaries, lists, and categories. We live within power structures that control the boundaries of our understanding. Oyeyemi troubles these boundaries.

As Oyeyemi shows us new ways of reading our world, her characters show us how to read theirs. The story inside the frame opens when Perdita goes in search of Druhástrana and consumes a lethal batch of gingerbread in her attempt to get there. While her daughter recovers (Perdita is rendered incomprehensible after the event), Harriet reprimands her, asking what the girl expects her to believe: “That you went to Druhástrana, that you went there somehow without leaving this bed . . . even though you would have had to leave this bed to get there. Perdita, because as I have been saying all your life, Wikipedia doesn’t get to decide which places have actual geographic existence and which don’t.” Perhaps to prevent her daughter from taking another such drastic measure in the future, Harriet decides to “play along” and tells Perdita the story of her life, or at least one version of it. Because Perdita cannot communicate verbally during this time, her dolls interrupt Harriet’s narration to question when “mother-of-Perdita” decides to answer the pressing questions (e.g. the identity of Perdita’s father). Ultimately, Perdita’s dolls remind us of where we began. They are companions and classic horror spooks, wise guides and no-nonsense proxies. Still, even Perdita’s dolls have autonomy in Oyeyemi’s world—the inanimate made animate also get to decide whether a reader is worth their time. They do not exist for our entertainment, no matter how entertaining we find their presence. They owe us nothing.

The best storytellers interrogate the status quo, the foundations of the fundamental. The best storytellers do this while convincing us they are doing something else, like laying the groundwork for a gripping love story, a family drama about the wealthy boy and the poor, immigrant girl. And that’s fun, sure. But what is a drama without the political questions? What separates an “immigrant” story from a drama? Why do we look for the difference? What powers tell us there must be a difference? When gingerbread—a resource meant to be bartered—is wrenched from the maker’s hands and commodified, we see the forces of capitalism in Clio Kercheval and the rest of her clan. In Gingerbread, the nation state and the market economy are echoed in familiar lives, like the deep-pocketed family whose allotted “good deed” one year is to house their distant relatives from Druhástrana.

Oyeyemi’s characters (dolls and changelings included) shine in dialogue. They also grab our attention in precise description—many are striking in their entrance, whether through a “beauty spot” or a shirt collar stained like blood spatter. But if those do not enchant you, the dialogue will. (You will need a pen, or something to record all the lines you will want to memorize.) There are many kinds of transformations in these pages, and one of the most remarkable is that which happens in the prose.

Consider the following passage, in which Harriet ruminates about her childhood friend Gretel, particularly Gretel’s dream relayed in a letter through carrier pigeons:

Gretel dreamed quite a Druhástranian dream. I mean, the absence of inclination to pass commentary, a reluctance to subscribe to any ideology in case the compromise proves catastrophic; those aren’t the only clues as to the Druhástranian nature of this dream. What about the fear that not having a point of view is in some way a crime? If this dream had been dreamed by a non-Druhástranian perhaps it would have had moral or spiritual overtones, or nationalist ones, or Gretel would have dreamed we were in a psychiatric hospital being treated for this chronic lack of a point of view . . . if we really must call the dream something, let’s just call it Gretelian . . . a mind-set that’s caught up in, even imprisoned by legality and correctness of form . . . what is that way of thinking if not Druhástranian? To be Druhástranian is to be dissatisfied with one’s condition until one can find some official personage to sign off on it. And if someone says that what you’re doing is all right today, won’t you need to get that approval reconfirmed later, get another stamp at some other desk a year from now? Of course this is a mind-set that a nation can be stunned into.”

In Gingerbread, the reader becomes a listener around a bonfire, lulled and attentive, because the world behind is dark and unpredictable and every detail in the light is crucial. For Harriet Lee, there are lists to keep track of places and people, but also to steer away from danger, where possible. Consider our first trip to Druhástrana, where our narrator tells us:

The fourth landmark was a dry well known as Gretel’s Well . . . If you dropped a stone in there, you had to listen intently for up to ten minutes before you heard it hit the bottom. This could mean that the well was exceedingly deep, or it could mean that some acquisitive creature lived in the well and thoroughly contemplated each stone it caught before deciding it wouldn’t do and letting it go. There was a tale . . . The name attached to it [the well] both suggested and withheld a story, and thus was invention forbidden. Children asked parents, younger siblings asked older siblings, and all were told: No story.

Of course we must know what lives in that well, for what is more alluring than a forbidden door? We are curious beings, for better or worse. All our stories agree on this. The delight in reading is to discover and rediscover what we know inside the house, inside the forest where the powers that govern our lives have fur and teeth, where we are without breadcrumbs to lead us home. In other words: patience. Patience and vigilance.

In a story, as in a house, there is a door to open and a door to close. Replace “houses” with “people” (and other objects), and the answer will be the same. A novel is a container, whether it holds a gingerbread house or a gingerbread girl. Some stories are easy to “open,” others not. Once we are invited through the opening, an exceptional guide like Oyeyemi points us in the direction where answers come in questions. Oyeyemi’s characters are readers too, and in their reading, of their lives and one another, we see ourselves more clearly.