Kristen Arnett is a queer fiction and essay writer. She won the 2017 Coil Book Award for her debut short fiction collection, Felt in the Jaw (Split Lip Press, 2017), and was awarded Ninth Letter’s 2015 Literary Award in Fiction. She’s a columnist for Literary Hub and her work has either appeared or is forthcoming at North American Review, Gulf Coast, TriQuarterly, Guernica, Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Salon, Tin House Flash Fridays, and elsewhere.

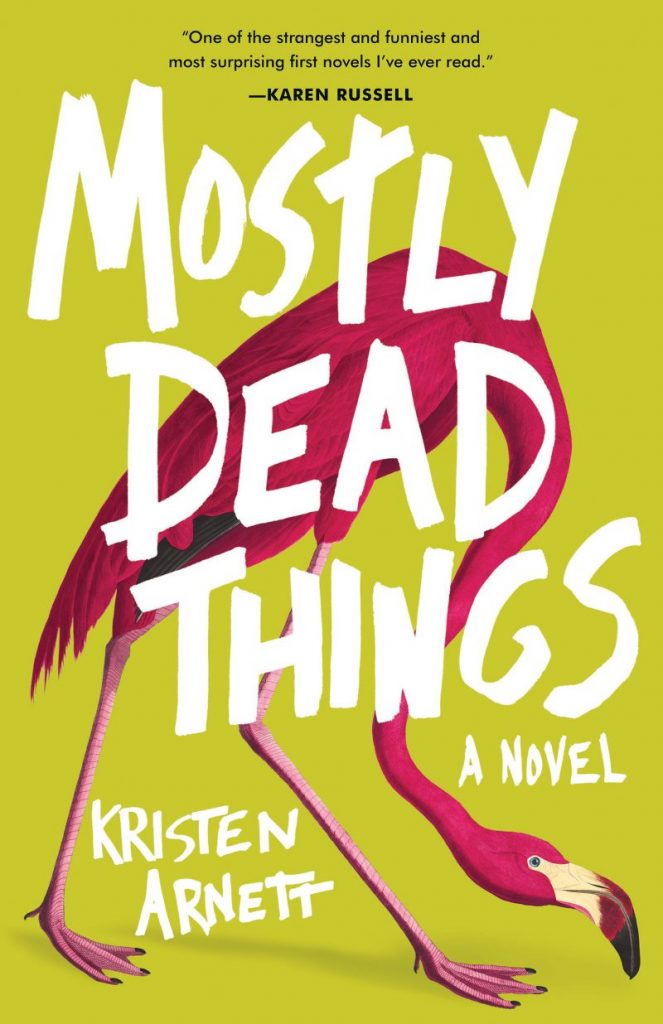

She is also a self-titled “7-Eleven Scholar™” and unofficially (or maybe by now it’s official) is one of the funniest humans on Book Twitter. Her debut novel, Mostly Dead Things, comes out from Tin House Books in June 2019. Mostly Dead Things tells the story of a young woman, Jessa-Lynn Morton, who is trying desperately to hold her family and their taxidermy business together in the aftermath of her father’s sudden suicide, but in the process of saving everyone else, she realizes she is quickly losing control of herself.

I interviewed Kristen over the phone to discuss her inspiration behind the much-anticipated novel she recently called her “gay Florida taxidermy baby” as well as the importance of place and memory in and outside of her work.

*

CF: This is such an original concept for a novel! I’ve literally never read anything like it. What was the first seedling for Mostly Dead Things? What inspired you to start writing it?

KA: I was at the Kenyon Review workshop a few years ago, and we were supposed to work on chunks of a larger story each day. Around that time, I had been thinking a lot about really bad taxidermy. I had been Googling it a lot and looking at pictures of it because I just found it funny. A lot of them were popping up on Twitter and I became obsessed with them because they really cracked me up.

The universe was trying to tell you something, I guess.

Yeah! It was so funny to me. So I thought, let me try to do this idea of a brother and sister who taxidermy a goat for their neighbor. You know, as a beloved pet. Then they fuck it up really bad. To me, that was so funny on many levels. But also, the dynamic between the brother and the sister after they fuck it up, like in the arguments that they would have as they tried to fix it, was also hilarious to me. So really I’d say the novel came from Googling pictures of bad taxidermy. I mean, I would just weep looking at them from laughter.

Is there a picture that sticks in your mind as the worst possible case of “bad taxidermy?”

Oh man…there are so many bad ones. There’s this one of a lioness and she just looks insane. Her eyes are crossed; she’s supposed to look very ferocious. If you google “bad taxidermy lion” it will probably pop up. It’s so bad. It looks like someone sat on it.

From bad taxidermy, I became thinking about the logistics of actually performing taxidermy. I began looking into how things can go so wrong in taxidermy. The placement of eyes is so important; even if you screw up just a little, the animals can go crosseyed. The more I got into that, the more research I started to do. Looking at it all, I got very obsessed with it.

I’m curious—did you grow up surrounded by taxidermy? If not, I am so impressed with the way you made me feel as if my own hand was the one extracting intestines and sewing up knife cuts. Your writing is so viscerally in the body! Did you ever try taxidermy yourself?

No, I don’t have the hands-on kind of experience. I really wanted to have some. But I did buy some taxidermy just so I could mess around with it. One was this squirrel on a Barbie bicycle and I opened it up just to see what they did with it. That was the most morbid thing I did; I was just really interested. Then I had to get rid of the squirrel because the dogs were losing their minds over it. They wanted to eat it so bad.

I think there are these binary ideas that things are either beautiful or ugly, and a lot of the time I feel like they’re not one or the other; they’re a mix of things. Like I think people are disgusting, but also there’s so much joy in that. There’s so much that’s interesting about how gross we are. I mean, what is gross? Intimacy is also disgusting and beautiful. Being intimate with a person means loving all the disgusting things about them. Writing about taxidermy was that way too. Kind of like falling in love with the thing you’re trying to open up.

As someone who presumably likes living animals, was it ever difficult to discuss deceased creatures in such a matter-of-fact way?

I do love animals very much, the ones in the novel too. I specifically didn’t want there to be any hands-on murder. I mean, there are instances, like when the peacocks get killed. But I was mostly interested in what was happening post-mortem, because that’s what Jessa is most interested in. When she gets the animals, she’s like “How do I resuscitate this? How do I bring it back?”

That also parallels Jessa’s family story—she’s dealing with the memory of her father post-mortem. The novel really melds these two parts of Jessa together: the work of taxidermy and her grief.

I was interested to see how Jessa interacts with death. Like what does it mean for her to deal with grief because she’s such a person who is able to compartmentalize things, or has been able to in the past. The story opens with her father’s death and she has to try to figure out how to deal with it. And then we view the kind of gradual breakdown of all the coping mechanisms she has throughout the book. She cannot continue to exist in the ways that she’s been choosing to. The ways she’s been attempting to cope with things no longer work.

I was fascinated how, throughout the novel, Jessa began to view people as taxidermies themselves. How she talks about her love interest Lucinda Rex’s body—it’s pretty hot, but also brutally anatomical! Jessa’s aware of her psychological tendencies and doesn’t love this quirk about herself. She says, “I was the kind of person who’d wish death on a creature just so I could make it my own.”

That’s a way that Jessa allows herself, for much of the book, to be tender or intimate. To think about people in the same kind of way that she is tender and intimate with the art pieces she’s trying to make. It’s a bad coping mechanism that eventually stops working. There’s only so long you can do that before it’s just a complete breakdown.

Going off of that, there was a specific thread that I saw developing throughout the book. Jessa returns again and again to the difference between needing and wanting something or someone. Jessa is often dissatisfied with herself, especially when she can’t manage or solve problems on her own, and you certainly throw many problems at her to face throughout the novel! Jessa seems to reject the idea of needing help. She says, “To need meant to be vulnerable. It was one of the scariest things I could imagine. Needing anything meant you were open to invasion. It meant you had no control of yourself.” Later she adds, “I never knew what I wanted. And I didn’t want to need anything. Better to need nothing, nothing never hurt you when it left.” How did this thread develop in the process of writing Mostly Dead Things, and what are your own thoughts on this question of need versus want?

As I was writing the book, I was thinking a lot about the use of power and control, specifically for Jessa’s character because she is such a control freak and wants to be in complete control—not only of her way of manifesting emotions, but also of the people around her. She wants to be in control of how they behave, but also how they think and feel. To want something, there’s power in that. But to need is very vulnerable.

Jessa patterns herself after her father by watching how he behaved for her whole life. Even when she has these memories of him being sick, he doesn’t want to need. He doesn’t want to have to carry burdens. I think there’s this idea that the need to need makes you a burden for other people. Jessa not wanting to do that for other people actually makes it so people want to help her. It’s like when you don’t want to be vulnerable to other people, but in reality, those who love us want to be able to support and provide care for us.

It was interesting to discover this about Jessa, because it’s just something I think she’s been fighting the whole time. To admit that kind of vulnerability means to give up control, and that’s so hard for some people. Some people never can, and if you’re unable to give up any little bit of control, it makes it so that intimacy is almost impossible. It makes you closed off, it makes you preserved as you are, and you can’t interact effectively or have good, lasting relationships if you’re unwilling to share any part of yourself.

But we do get to see some of Jessa’s attempts at intimacy, even if she ultimately ends up failing. The novel is beautifully sequenced, alternating between the narrative present and flashbacks of Jessa’s past with her lover, the wild and heartbreaking Brynn. Did you always know that the book would tell Jessa’s present and past in tandem?

Yes, there were only a few things I knew I wanted to do when I started out writing the book. I knew that I wanted it to be about this specific family. I knew that I wanted it to be based in Central Florida. I knew that I was going to use a lot of taxidermy in it, and I knew that I was going to alternate the chapters so that every other chapter was a flashback. I knew that the present was going to be very linear and connected. But I wanted every other chapter to be how memory functions, which is not at all linear and is very sporadic. It’s often prompted by some kind of smell or image or taste. I wanted the past to be a thing that cannot be controlled, and something that was going to pop up regardless of what Jessa wanted.

I knew Brynn was going to be a big character in the book, but as I was working, I realized I wanted her to be in Jessa’s memory. So you get to view Brynn how Jessa wants you to view her. In times when Brynn doesn’t act the way Jessa’s expecting, it’s almost like someone is surprising her in her own memory.

That was the one constant story I was pulling through. I’m not a person who outlines at all. I had a Word document that just had people’s names and places, but that was basically it. In order to get through the novel, I just moved forward as I was working. I had no idea what was going to occur in the book other than the beginning. I knew it would open with Jessa’s dad dying, because I wanted that to be the catalyst for Jessa’s story.

Otherwise, I didn’t know what would happen, which is how I like to write. For me, if I know what’s going to happen, then I’m writing into the plot instead of allowing myself to be surprised by what happens. I think the reader will also be able to guess what’s going to happen, and I don’t want that. I want to be writing into the surprise. I want to be interested about the turns it’s going to take.

This novel is not only a story about family secrets and grief and love. It is a story about Florida, too. As Jessa and her brother Milo drive around town, we see through their car window Florida’s convenience stores, its strip malls, its retirement housing, its FOR RENT signs everywhere, its gentrification, and constant construction. We’re also reminded that the Seminole people once lived on this land. Jessa says, “It was what Central Floridians did: pave over everything so they could forget what had been there before.” Other than the fact that you are a Central Floridian yourself, why did you choose this particular setting for the Morton family’s story? What fascinates/confuses/upsets you about this landscape?

In the book, I think I refer to it as a “collective amnesia” that people have living here. It truly is a way that people have of not holding on to place memory here. And since I’m so obsessed with place, specifically Florida, it’s been very fascinating, and by that I mean frightening, to look at, because if you’re choosing not to remember, that means you’re not learning from anything that’s occurring.

I’m third-generation Central Floridian, and I have had conversations with my grandma in the past. She grew up here. There are places that were here for thirty years and I asked her about them and she doesn’t remember. Once something else goes up, that’s the new thing. There’s this constant need to refresh. So even a McDonald’s gets an uplift every couple of years. Everything has to be new, even if it’s the same thing. I’ve heard people refer to it as “progress,” but it’s legitimately just replacing some thing with the exact same thing. I wouldn’t call that progress.

On my book tour, I’m going to do my launch at this place I used to go to when I was a teenager. It doesn’t exist in the same location now. It’s called Park Ave CDs because it used to be on Park Avenue and nobody remembers that it used to be there. That wasn’t even that long ago.

It used to be that people who grew up here would leave. I think that’s happening less now, so hopefully there will be more of a community memory of places and art. We have a small but growing community of people in Central Florida who are pushing for art to flourish here, which is excellent.

In Mostly Dead Things, Brynn mentions that she doesn’t want to be one of the people who stays in the town forever.

That’s something I’m interested in, too. Exploring what home looks like for people, and is it a place where you need to stay or leave? For Jessa, who is very afraid of change, it’s not a bad thing for her to necessarily stay there. But then there are people who live here and don’t travel.

Right, Jessa’s never been outside of Florida before.

There’s not a need to move away from where you are, but there is a need to expand and understand how you fit into the bigger, broader world. Understanding how you fit rather than thinking that the place where you live is the world.

What’s something that most people living outside of Florida wouldn’t know about your state?

Florida is so broad, you can’t talk about it holistically. Miami is not Orlando, which is not the Panhandle and is not the Keys. The cultures and communities of this state are all wildly different.

I specifically don’t say Orlando in my book because I knew that if I did, people would have preconceived ideas of what Orlando is. You know, theme parks and all that.

I do name Paynes Prairie, because I wanted any Florida person to read it and know what I was talking about. I mention St. Johns also, which is close to here. There’s so much to do here in the natural environment, and I don’t think people know that about Orlando. There’s all of these fantastic natural springs, there’s hiking trails, and we’re so close to the beach. I’m outside all year long! It replenishes me as a person.

Speaking about replenishment, you are so generous in your ability to let each character grieve in their own personal way. For Jessa, it’s working tirelessly in the taxidermy shop and taking care of others. For her mother, grieving comes in the form of constructing quite unique art installations featuring the mounted animals in various sexual positions. What do you do when you need space away from all the noise and sorrow in the world? Does nature play a part in that for you?

Absolutely. I think it’s also a way for me to think about work and writing. There’s a lake very close to my house and I like to walk around it very late at night. You can feel like you’re by yourself. Also, it’s just so helpful to think about work in a way that during the day I’m not able to do, being plugged in to all the different things I’m doing, like staring at my computer or my phone.

Or being at the library where everyone is asking things of you!

Yeah, so it’s nice to have this time to completely unplug and just be present in the world and feel small in it. It’s a nice reminder to remember how small you are in the space of things.

On the topic of writing and work, there’s a passage near the end of Mostly Dead Things where Jessa explains the importance of suspension of disbelief in the mounting of the taxidermy pieces. She says, “The mount meant that the animal had a place to live; it had a home. If the mount was wrong, everything looked fake. It took you out of the magic. Mount it right, my father said, and you gave your audience something to believe in.” I couldn’t help but see this as a possible metaphor for the art of fiction writing! How do you know when you have that “just right” amount of magic in your work? What is your “mount?”

I guess that’s really hard to know! I never feel when I’m working that “Oh, this is good,” but I can sometimes get the feeling when I’m writing like “Huh, I don’t know what this is, but it’s working toward something.” And what that thing looks like can vary. Is it making me think more? Is it opening up into a broader question about something? Is it making me interrogate an idea in a new way? And if it’s doing that, then it’s something I think is worthwhile.

Another thing, too, is that I’m such a place writer. If the place is there, maybe that’s the mount for me. If the place is there, then it’s holding the people right for me. I can have them really tethered and able to move around and do whatever weird surprising things they’re going to do. It’s the same in my short fiction, too. If the setting is right, it will allow for something bigger to happen.

Thank you again so much for chatting with us at MQR! From writer to writer, I have to ask: What are some of your favorite books you’ve read so far this year?

KA: There have been a lot of great books this year! I got an early copy of Jami Attenberg’s phenomenal book, All This Could Be Yours. It comes out in October and it’s going to blow up, I think. Bryan Washington’s story collection, Lot, is very much place-based in Houston. It’s one of the best story collections I’ve read in a minute, and I love story collections. I’m also in the middle of reading Yiyun Li’s gorgeous and heartbreaking novel, Where Reasons End. Her fiction is captivating.

And then of course, there’s T Kira Madden’s Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls. It’s fantastic. I’m reading with her on my book tour at Greenlight in Brooklyn on July 1st. I’m also reading with Esmé Weijun Wang in San Francisco. I think I read Esmé’s book, The Collected Schizophrenias, in two days. You’ll just devour it.

Find out where Kristen Arnett will be reading from Mostly Dead Things here, and make sure to follow Kristen on Twitter for her daily dispatches from 7-Eleven and much more!