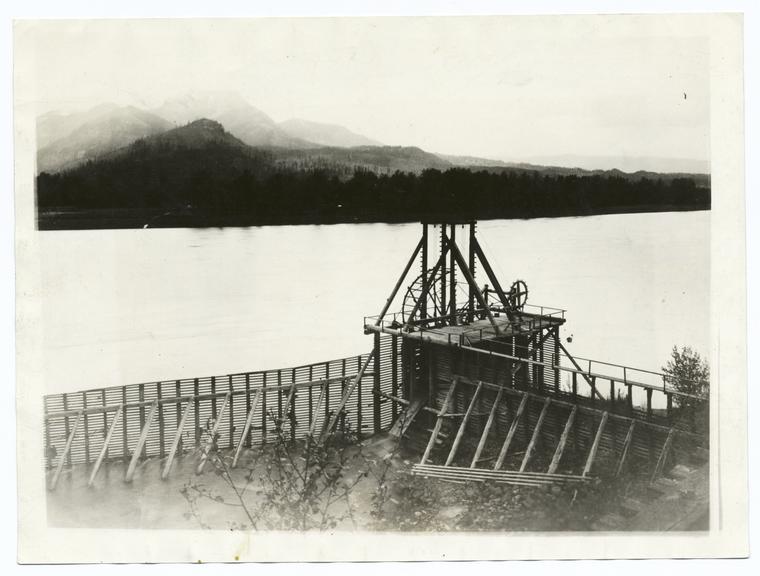

Sometimes, I feel like a river. I had the perhaps uncommon experience of attending an MFA poetry program directly after undergrad, which allowed me to delay, until my mid-twenties, any real consideration of what work I planned to do for humans other than myself. “Like us, rivers work,” argues Richard White in his landmark environmental history. “The story, told simply, is that human labor dammed the Columbia so that the river could do work other than its own.” If the MFA impressed anything upon me it was to treat writing as real work, my work. Afterward I found myself unharnessed by society and at best ambivalent about the prospect of being dammed.

I moved on a whim from the Midwest to New Orleans, where the economy is built primarily on tourism. This compels many of the city’s most talented and passionate young people to divert at least some of their energy to the service industry, as other kinds of jobs, if you want them, are simply in short supply. Still, it turns out that the only thing worse than a crap job is none at all: “I rode the elevator, / empty because everyone had a job but me,” wrote Gary Soto. At 11 AM on a Tuesday an elevator feels awfully empty, and I felt empty too, so I took a few service jobs and waited to hear back from any kind of 9-to-5. There were expectations on me, after all, and I could sense them gathering force in the distance, like a tropical depression that may or may not touch shore.

While working in service I began to feel a bit like Simone Weil, the sheltered, awkward, mystic-intellectual who at twenty-five decided to work in a factory for a year, not out of financial urgency but for political solidarity, as a kind of investigative journalist.  It didn’t go well for her. As Czeslaw Milosz wrote, that year “destroyed her youth,” and taught her that such self-sacrificing labor is not noble but in fact degrading, as it required her, just like her less privileged comrades, to wholly give up a sense of self. I told myself I would keep writing no matter what, but after placating the herds, mopping floors, and cleaning toilets, I didn’t always feel inclined. As Weil wrote in her diary, “The temptation to give up thinking altogether is the most difficult one to resist in a life like this: one feels so clearly that it is the only way to stop suffering.”

It didn’t go well for her. As Czeslaw Milosz wrote, that year “destroyed her youth,” and taught her that such self-sacrificing labor is not noble but in fact degrading, as it required her, just like her less privileged comrades, to wholly give up a sense of self. I told myself I would keep writing no matter what, but after placating the herds, mopping floors, and cleaning toilets, I didn’t always feel inclined. As Weil wrote in her diary, “The temptation to give up thinking altogether is the most difficult one to resist in a life like this: one feels so clearly that it is the only way to stop suffering.”

Okay, she’s being a bit dramatic. But in a way, that’s the crux of the matter: whether or not to give up thinking – by which I mean, of course, writing – once you’ve come up against the hard edge of time and economics, against the gravity of existence. Menial work might discourage the mind, but even a purposeful job diverts your energy and submerges you into a reality where the hours of your day are worth some quantifiable amount, a reality antithetical to those hours of unpaid creative effort that so often come to naught. To settlers, the Columbia River’s current looked like a waste of energy, and building dams seemed only logical, even natural. What a relief it would be to throw the self into a predictable career, to turn all your creativity and purpose toward an activity that garners a paycheck. To hold onto this other, aberrant tendency in any serious way puts you a disadvantage, and given the slim chances of financial reward, why would anyone want to do it?

In writing about the Columbia, White attempts to define nature as the “unmade world,” that essential element of the river that was not created by humans. We can alter a river – make it fast or slow, wide or deep – but there is still something there that we did not do. When we speak of a person’s nature we speak similarly of something that seems untouchable in them. Even if it’s likely ingrained by years of experience, not simply inborn, the result is the same: there is a way the person wants to flow. For better or worse, this quite real feeling – that writing is in my nature – is part of what brings me back to the page, and I’m sure that’s true for other writers, as well. Early modern writers referred to their craft as a vocation or calling, and I’d argue this notion still shapes how writers think about their work and identity. In a way, these terms cede agency, as if poets just can’t help but make and break lines. “Milton produced Paradise Lost for the same reason that a silkworm produces silk,” Marx wrote in his definition of “unproductive labor.” “It was an activity of his nature.”

It may feel like poems are inevitable, but of course they aren’t. Today a career counselor would probably advise Milton to find steady employment as a grant writer or social media manager, which would certainly be a more sensible use of his nature, given that he sold his epic poem for just ten pounds. Well-meaning people tell me all the time that “society needs good writers,” and sure, I can write excellent emails and SEO articles and whatever else, until I grow resentful that I’m wasting my linguistic sensitivities on actual garbage. When those industrial developers built dams and factories and nuclear plants along the Columbia, which all in some way used, altered, and destroyed the river, they literally didn’t have customers for the energy they produced. No one wanted it; the companies had to create the demand, had to find people to populate the area. Forgive me, but if I’m the river, I can’t help but be a little cynical about the work I “should” do.

Of course, I’m not a river; I pay rent. Neither am I Milton. Post-MFA, I’ve simply found myself in a world that insists purpose and identity arise from your job, such that I’ve found it necessary to defend the useless parts of myself, even while I strive to join the workforce. If you want to write, just valuing your own work is half the battle. It may be in your nature to write, but that alone won’t do it. Within the comfort of an MFA program, your professors and peers swap advice about how best to divvy up your days and ignore the world as needed. But outside the program, it’s just you, your self-doubt, and friends who want to actually hang out, not stare at screens together. So much of the labor of poetry is simply to insist that writing is, in fact, work in a meaningful sense, deserving of time and sacrifice.

It helps, a little, to remember that the very root of poetry — poiesis — means to make or craft. W.S. Di Piero says poets “do thought work and make thought things,” which at least suggests this isn’t nothing. To be a writer is to have reached the strange but real conclusion that the best way to address the world – even and especially the world’s suffering – is, in fact, to think about it. Those lost hours don’t look cute on your resume, but no matter. If it’s possible to value a river for more than its supposed economic worth, to preserve a landscape even when that choice goes against financial advantage, then I like to think it’s possible to value parts of ourselves the same way.