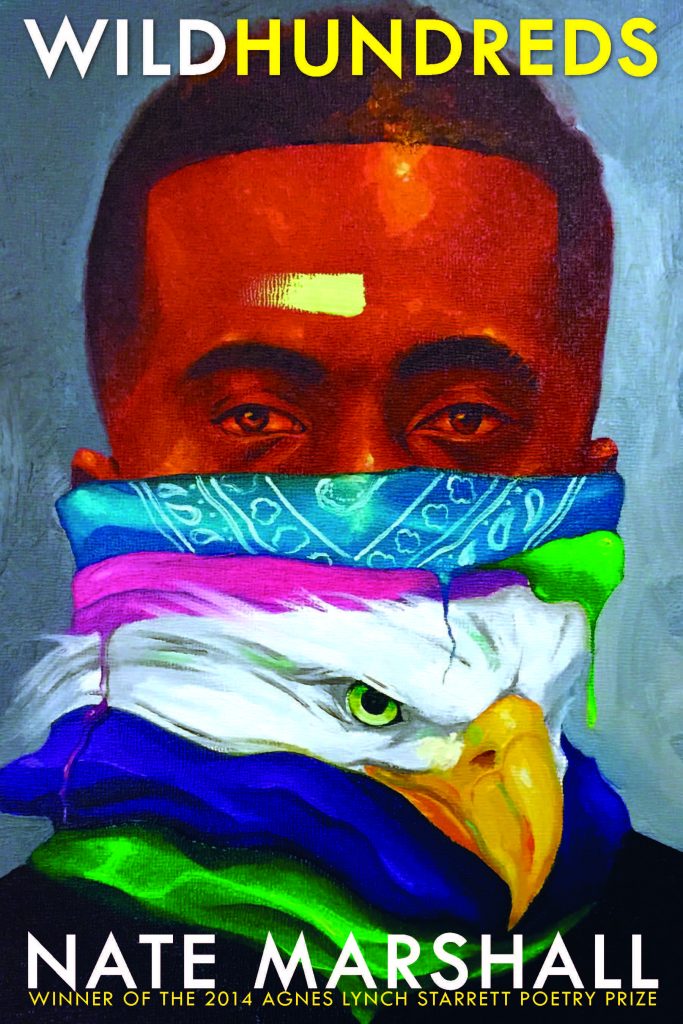

It’s been a big year for Nate Marshall. This spring, he co-edited The BreakBeat Poets, the first poetry anthology by and for the hip-hop generation. His rap group Daily Lyrical Product released an album, Grown, this summer. Just last week he was named a recipient of a 2015 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Poetry Fellowship. And now his debut collection, Wild Hundreds–winner of the 2014 Agnes Lynch Starrett Prize–will be released this month by the University of Pittsburgh Press.

Wild Hundreds announces its presence when it enters the room. It is part love letter to Marshall’s neighborhood in Chicago, part exploration of the experience of a young black man in America, part indictment of the system that presides over it. It’s thunderous and plaintive, sometimes managing to do the impossible and straddle both. Take “out south,” which asserts: “shake us. we make terrible tambourines. / packed into class, kids passed like kidney stones.”

The collection brings its readers to a city alive and bright and then out into the world with the city still burning in its heart. Meanwhile, underneath pulses the risk of being young and black, the erasure of these lives and experiences. We see it in “Harold’s Chicken Shack #86,” where Marshall calls the removal of the word “Shack” from “Harold’s Chicken” “easier, sounds like Columbus’s flag stuck / into a cup of coleslaw / shack sounds too much like home / of poor people, like haven for weary.” We see it in “prelude,” where the speaker considers that “RIP” might be a girl because he sees her name beside the names of other boys. “Chicago high school love letter” simply implores: “hold me / before / i / disappear.”

Marshall’s collection is carried through by the energy of its style, a lyrical and unpretentious diction that keeps the work tight and engaging. It is deeply political and deeply emotional, a celebration of place and life and survival that cannot afford to ignore the danger that permeates it but still swells with love regardless.

I had the pleasure of asking Nate Marshall a few questions about his collection, his process, and his fantasy syllabus.

*

To begin simply: when did you start writing poetry?

I started writing when I was about 11 or 12 and I started really taking it serious when I was 13 and exposed to the youth poetry slam in Chicago.

You dedicate this collection to the victims of state-supported and -sanctioned black death. At what point in the process of writing Wild Hundreds did it become clear to you this was one of the issues driving you?

I think it was always clear for me. I grew up as a black boy in a somewhat rough neighborhood in a city that is notorious for segregation, divestment, and police misconduct. For as long as I’ve been writing I’ve been thinking about these issues. One of the things that actually made me start writing was the first time I was stopped and harassed by the police the weekend of my 13th birthday.

There’s a line in your poem “Harold’s Chicken Shack #35” that has been haunting me: “gravel / is necessary food.” It’s the last line. James Baldwin talks about the job of the poet or the revolutionary to be to “articulate the necessity … until the people themselves apprehend it.” Do you have these necessities–these great, harsh truths–in mind before you sit down to write a poem or do they emerge later on?

I think for me I don’t approach the page with some necessary truth that I’m aware of as I enter a poem. Often my poems start with a story or a fragment that I want to communicate or display for people and embedded in those things is a truth that reveals later.

Wild Hundreds opens and closes by announcing that it’s a “long love song.” On the subject of music, you also have a rap album, Grown, out this year with your group Daily Lyrical Product. So many rappers–Tupac, Saul Williams, innumerable others–were/are writing poetry before and concurrently with their music, if we can even call these two discrete genres. How would you describe the relationship between the work you do as a poet and the work you do as a rapper

For me they are very much interconnected. I think the way I think about rhythm and sound in a poem is of course related to having a background in hip-hop. I think also the approach of having poems that speak to people in accessible language. All of that comes from hip-hop.

You’re a teacher. If Wild Hundreds is on the syllabus, what are students reading, watching or listening to alongside it?

Ha. While I would never teach my own book of poems, I could imagine a class that discusses 21st Century Black Masculinity in Popular Culture and includes my book, Ta-Nehisi Coates new book, Kanye’s first album, Kendrick Lamar’s first album, the book 40 Million Dollar Slaves, Frank Ocean’s album and the letter where he comes out, Danez Smith’s books, and some other stuff. That would be a fly class.

*

Wild Hundreds is available on Amazon.