The last time I left, we were two. Now I’ve returned to make five. I went away from New York for a year and came back to a very full apartment.

I wasn’t planning to stay long. In our old apartment, that is, where what was my office is now someone’s bedroom. I insisted to my boyfriend that as soon as I got back to the city we’d need to find another home all our own. Ian suggested it might not be so easy. I suggested I’m too old for roommates (even great ones like ours luckily are). Ian suggested my thirty-one years doesn’t entitle me to shit in this city.

But still, we had a look. On our first full day together again, a glorious late summer Sunday, we did not go to Coney Island or Central Park or the MoMA. Instead, we met A.J. the broker on Caton Street and got in his car within a minute of meeting. We let him drive us places, show us things; we laid ourselves at his feet. The last apartment he showed us that day was a spectacular space in a building already inhabited by a friend of ours. It was a one-bedroom on the 10th floor with an expansive view of Brooklyn’s rooftops below. It was large and airy. It had “closets for days” (A.J.’s phrasing). It cost $50 less per month than the apartment we currently live in. We’d paid that rent just the two of us before, always on time, never a problem. We loved this place instantly, and told A.J. so. He asked us what we do. I said with all the earnestness I could muster that I’m about to get my PhD. Ian responded that he’s a freelance musician and music teacher. A.J. looked concerned. He told us he didn’t think we would qualify for this apartment, that we’d need to show we make a combined income of $62,000 a year. I suspected we’d be a bit short. The next day, I put together our tax returns from the year before and confirmed we were quite a bit short. We decided to follow up with A.J. anyway, to vouch for our own responsible behavior and all around desirability. We spent some time meticulously crafting one long paragraph in which we said how much we liked him, and hoped he’d reach out to the building’s owner on our behalf. We highlighted all the key points with the appropriate emojis, and texted it off. “Hey ian will do,” came the response, quickly. And we never heard from A.J. again.

~

New York has a way of making you feel really down in the gutter, this short-lived apartment search in South Brooklyn a case in point. The NYU kids are moving here, A.J. had explained with a shrug. When I was an NYU kid, I lived in Astoria, Queens. And when I went to Columbia, I lived in Washington Heights. I’ve been priced out of both of those neighborhoods since; I’ve been both gentrifier and gentrified.

It’s a messed up city and it makes me mad as hell, and yet, I love this place all the same and all these years. In Joan Didion’s famous swan song to New York, “Good-bye to All That,” written in 1967 after three years gone, she describes arriving in New York at twenty, and feeling “that it would never be quite the same again.” I came to New York from Los Angeles when I was an impressionable eighteen, and to be sure, it’s made all the difference. But bad things happen when you move to New York young. At least, bad things happened to me. Didion writes about being young in New York as the time when, “I could stay up all night and make mistakes, and none of it would count.” This was not my experience. I felt very hard how the mistakes did count, how they hurt my physical and mental self. But I did not hold this against the city, I blamed it on myself. New York (and my dog) have some messed up special status where they can keep treating me bad, and I keep forgiving. Because, well, love.

It’s a messed up city and it makes me mad as hell, and yet, I love this place all the same and all these years. In Joan Didion’s famous swan song to New York, “Good-bye to All That,” written in 1967 after three years gone, she describes arriving in New York at twenty, and feeling “that it would never be quite the same again.” I came to New York from Los Angeles when I was an impressionable eighteen, and to be sure, it’s made all the difference. But bad things happen when you move to New York young. At least, bad things happened to me. Didion writes about being young in New York as the time when, “I could stay up all night and make mistakes, and none of it would count.” This was not my experience. I felt very hard how the mistakes did count, how they hurt my physical and mental self. But I did not hold this against the city, I blamed it on myself. New York (and my dog) have some messed up special status where they can keep treating me bad, and I keep forgiving. Because, well, love.

Didion writes of her drive from the airport upon first arriving in New York as a both mundane and magical experience, observing from a bus the “wastes of Queens and the big signs that said MIDTOWN TUNNEL THIS LANE and then a flood of summer rain.” It’s not surprising, hailing as she did from California, that those rains would hold in her memory. The summer rains here are like nothing I’d known growing up in Los Angeles, in a constant state of desert drought. In August, it can get so hot in New York that the air between buildings feels like it has nowhere to go, until it breaks into a storm and spills all over everything. A cathartic running through the streets commences, as people caught unaware seek shelter. The rains quickly subside, the day’s routine continues, just a little soggier. This never gets old for me. The “wastes” of Queens also signaled for me some sort of idyllic alternate universe of colorful clapboard houses, two stories tall, when I first glimpsed them from the highway. They looked nothing like the low ranch style homes I grew up with in the San Fernando Valley. During my college years, I made the trip through Queens to Manhattan and out again often as I nannied on Shelter Island in the summers and returned to the city by bus on weekends. To me, the cemeteries we’d pass on the way out to Long Island were always those in Kerouac’s On the Road, and the billboards that lined the lanes of cars heading back into the city recalled T.J. Eckleburg’s optometrist advertisement in The Great Gatsby. It did not matter that I was riding the Hampton Jitney and not Gatsby’s Ascot; New York, when I was young, always made me feel a million bucks.

~

I am no longer interested in feeling rich; fortunately, I gave up that inclination years ago. And I see New York now for what it is most of the time: more Fritz Lang’s Metropolis than the film version of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. It’s a Wall Street wonderland that panders to the haves, is indifferent toward the have-a-littles, and is down right nefarious to the have-nots. Patti Smith and David Byrne suggest the creative sort get the fuck out. But David Byrne never left as far as I can tell. In Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates remembers his own first days in New York in his mid-twenties in a way that resonates, and if he lives in New York, I think, not all the good has gone: “Summer was unreal,” Coates writes. “Whole swaths of the city became fashion shows, and the avenues were nothing but runways for the youth. There was a heat unlike anything I’d ever felt, a heat from the great buildings, compounded by the millions of people jamming themselves into subway cars, into bars, into those tiny eateries and cafés. I had never seen so much life. And I had never imagined that such life could exist in so much variety.”

The variety persists here, stubbornly, despite the homogenizing effect of endless and indistinguishable luxury condos. There is the Chinese woman I saw yesterday using a parked Citi Bike as a stationary exercise bicycle, peddling backwards with the East River as her backdrop. And the break dancer who performed on the J train over the Williamsburg Bridge for a bunch of tired commuters who stared through him with glassy eyes as he did back flips in a moving train, and then lectured us on our apathy when he was through. There’s my neighbor Roman and his pear tree, which he planted in front of his house in the hope that it would inspire the rest of the block to envision a more beautiful version of the garbage strewn street we currently inhabit.

~

For Didion, New York got old at twenty-eight, eight years after arriving. Not quite so young anymore, she discovered that “not all the promises would be kept, that some things are in fact irrevocable and that it had counted after all.” Back in her home state of California, she writes of how she had felt to be “on some indefinitely extended leave,” never really “living a real life” in New York. Maybe it’s simply that I don’t feel myself to be living a “real life” anywhere, that I haven’t managed to live in one place for more than eight months let alone eight years. But I’m thirty-one, and ecstatic to be back in New York, despite the long time knowledge that my mistakes here always have counted.

All my moving around means that most of my belongings are in a storage unit in lower Manhattan. I take the F train there about once a week to get something I discover I need: a few extra dresses, some documents, or some printing paper. Soon, the summer heat will give way to a more temperate autumn clime, and I’ll have to dig out my cords and some sweaters. It’s crazy, but I love my visits to the storage unit, where I hang out amidst all the other no-monied New Yorkers looking at the things we can’t afford to keep, and yet can’t bear to part with. I walk there from East Broadway through Chinatown and the Rutgers Houses, all the way to the water, where the storage facility is nestled between the Brooklyn and Manhattan Bridges. I could never afford to live in such a location, but I am at least able to offer my books and records, art supplies and once-worn high heels this enviable address.

One of my favorite places in the city is just across the river from the Manhattan Mini Storage, at the Brooklyn Bridge Park in DUMBO. Sometimes I go there after a visit to the unit. I sit with my back to Jane’s Carousel and look across the water at Manhattan and the windowless building in which my things live. People are always posing here for engagement photos and headshots. The brides-to-be embrace their beaus awkwardly below the Brooklyn Bridge. On the Manhattan Bridge, the Q trains rumble past, quietly reminding me of my regular commute and where I could be, jostled against a whole lot of other folks, rather than down on the water, where the space feels so open. But it’s not so bad on that train, either; the view it proffers of the Brooklyn Bridge, as it rises aboveground out of Brooklyn and before it descends again underneath Manhattan, never gets old. On my commute, I make a point to pause in this moment, to look up from my book as we pass the Bridge and the Statue of Liberty, and what Ian calls the Army of Giraffes, a series of shipping cranes out on New Jersey. As we lift above the water, the ride can make me feel for an instant a part of something big, in a city that has a tendency of reminding us that we are all in fact very small.

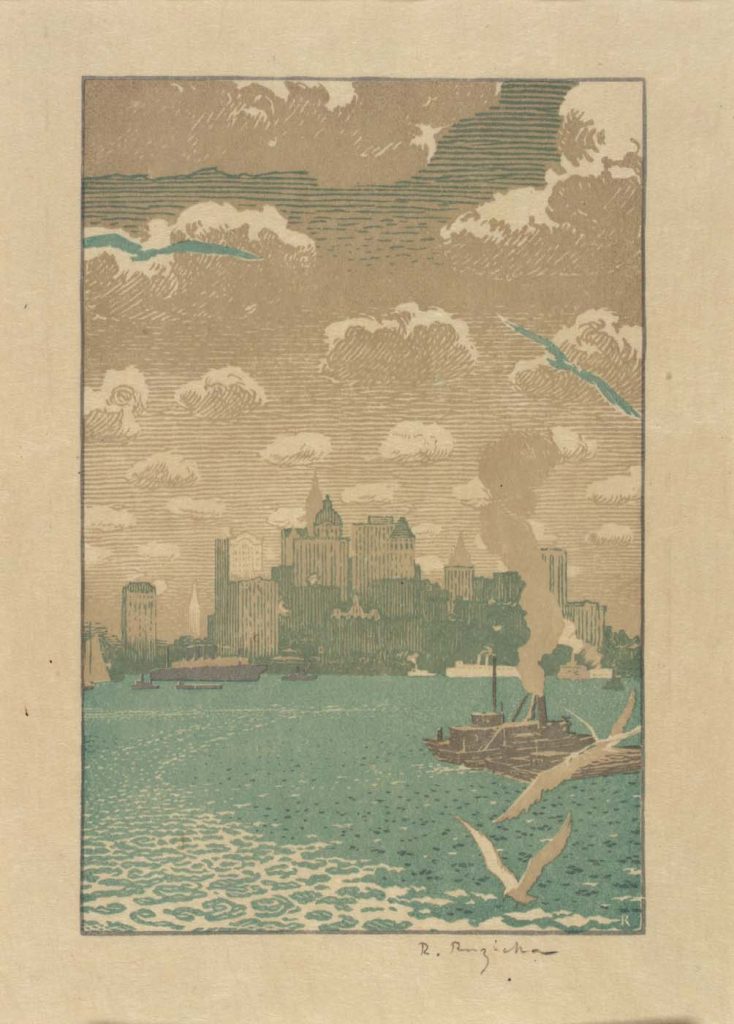

Lead image: Ruzicka, Rudolph. “Lower Manhattan.” Color wood engraving. Smithsonian American Art Museum, New York.

Inset image: Ⓒ Sasha Arutyunova, 2014.