Reviewed by Keith Taylor

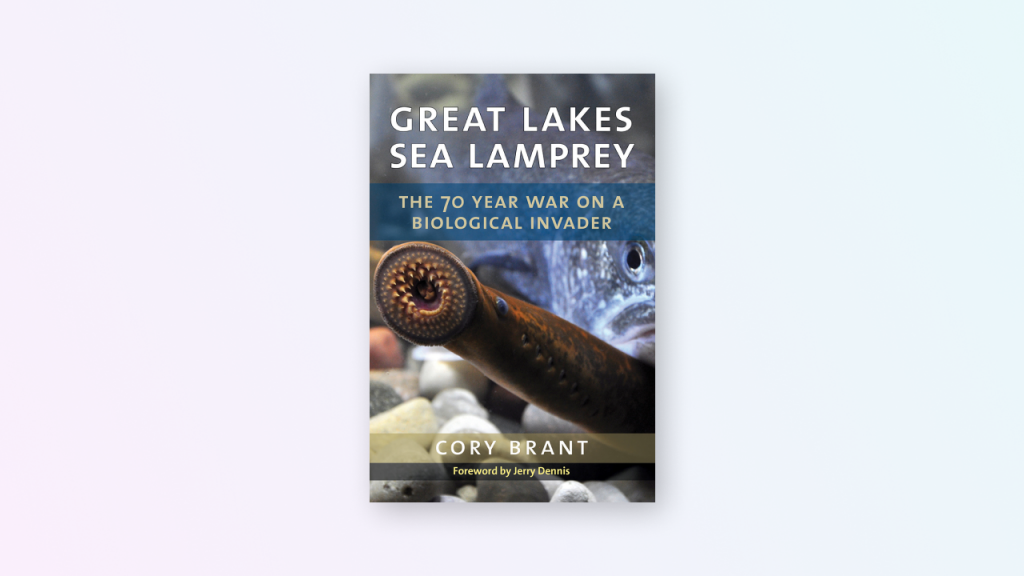

People who don’t know anything about sea lampreys – and maybe even those who do – might look at the cover of Cory Brant’s Great Lakes Sea Lamprey and think they are holding a volume of science fiction. The mouth of the lamprey looks like a giant suction-cup filled with small sharp teeth. It almost resembles some sort of horrible machine out of Star Wars or The Matrix. Behind the big circle of the mouth is a small, protruding blue eye. Brant gives us a better description early in this excellent history of the creature, its life in the Great Lakes, and the science that has tried to understand and control it – “This creature is one of the largest parasites on earth. It evolved an efficient way to feed long before animals could bite or chew. A jawless, suction-cup-like mouth containing rows of sharp teeth that look as thought they’ve been stained with coffee adorns the sea lamprey’s head.”

But typical of the way Brant has structured his narrative and his research, he quickly adds detail that makes the description both more specific and, in this case, even a bit more horrifying:

Calling these “teeth’ is incorrect; they’re more like small horns made of keratin—a structural protein that also makes up our hair and fingernails. The animal vacuums itself to the side of an unsuspecting fish while the horn-teeth assist with the grip. Thermal-sensitive cells inside the suction-cup mouth allow the parasite to distinguish between warm- and cold-blooded prey. They’re only interested in cold-blooded prey.

Although we have four species of much smaller native lampreys in the Great Lakes, the sea lamprey is a marine creature that is a comparatively recent arrival. It has possibly been in Lake Ontario for millennia, but was barred from the Upper Lakes by Niagara Falls. Since the 19th century, we’ve been looking for a way to navigate around that natural barrier. First the Erie Canal across upstate New York, and then the Welland Canal, passing through Ontario and connecting Lake Ontario to Lake Erie, allowed for people, materials, and new species to pass unimpeded to the Lakes beyond. By the early 20th century, the sea lamprey, “the most destructive predator ever to enter the Laurentian Great Lakes,” had arrived.

At this point, Brant begins the main narrative of his book. First commercial fishermen saw the devastating results of the sea lampreys. Their catches of larger fish – the lake trout and then the whitefish in Lake Superior – began to shrink. The fish they did catch were smaller and unhealthy and most had large circular scars on their bodies. Many came up with foot-long lampreys still attached. Governments became involved and hired scientists to figure out what was happening.

Brant has travelled all around the Great Lakes basin, interviewing fishermen and scientists. He clearly honors these people and the work they have done. Their pictures and their stories are scattered throughout the book. But he structures his story chronologically, focusing on the development of our understanding of this creature and the effort to find a way to control it. Once the scientists determined the breeding patterns in the inland streams, and learned that the worm-like lamprey larvae can stay buried in the inland mud for years before they emerge, swim to the Big Lakes and attack the fish, they knew they would have to focus their efforts on the breeding streams. By this time the Great Lakes fishery, at one point the greatest fresh water fishery in the world, was almost gone, wiped out by the voracious lampreys.

The scientists began looking, almost desperately, for a species-specific poison that would kill nothing but young lampreys. Brant is particularly good telling this story, making even the long lists of chemical names sound interesting. Scientists tested thousands of chemicals, until a series of lucky breaks brought them to 3-trifluormethyl-4-nitrophenol, the TFM, now famous among those of us who follow wildlife in the Great Lakes. By the early 1960s, the fishery had been partly restored. Salmon were introduced a few years later. Occasionally some would come up with lampreys attached or with the deadly looking scars the creatures leave behind, but mostly the fish did fine until that fishery found its own way to peter out. That, of course, is a different story. Now, the lake trout and whitefish are doing fine and supporting both the healthy Native and surviving commercial fisheries, even though the sea lampreys have never been completely eliminated.

Brant is frank about the contradictions his work has illuminated. He just makes passing reference to Rachel Carson, whose Silent Spring was published just a few years after scientists discovered the poison that would kill lampreys and which pointed out the devastating results of chemical assaults on the natural world. “What would Rachel Carson think,” he writes, “ of the program or the use of lampricide to control these creatures?” He also points out the “ironic twist” that is a result of our pollution laws from the 60s and 70s: “As rivers and streams around the Great Lakes become less polluted, they gradually transition into suitable habitat for sea lampreys.”

If we hope and need to have a healthy fishery in the Great Lakes we will always have to find a way to control sea lampreys. But Brant lets us know that it “is more than a fish story. It is a reminder of why natural things are important and how each ecosystem is connected.” By the detailed specificity of his Great Lakes Sea Lamprey, he has found a useful way of doing just that.