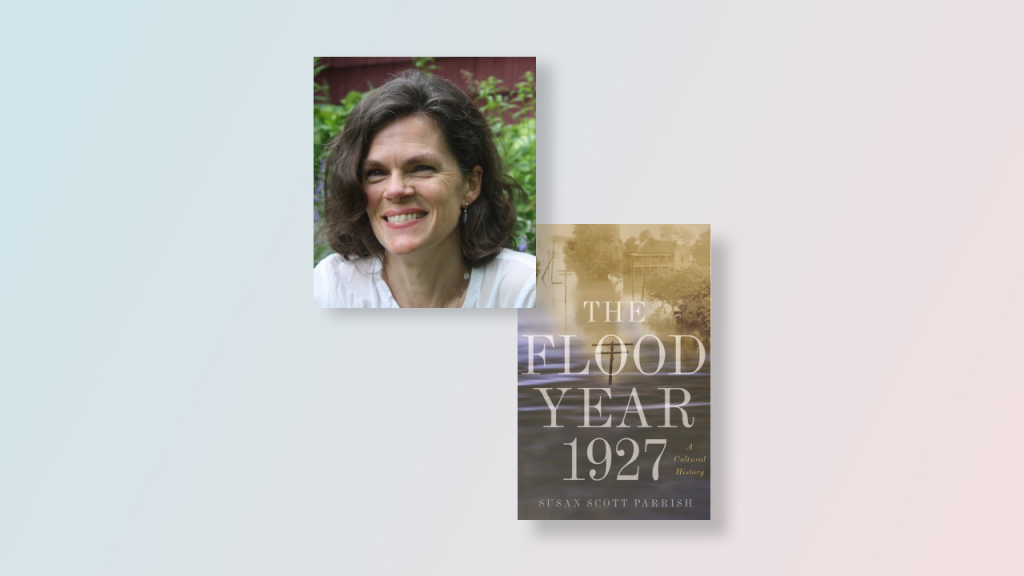

Dr. Susan Scotti Parrish’s research addresses the interrelated issues of race, the environment, and knowledge-making in the Atlantic world from the seventeenth up through the early twenty-first century, with a particular emphasis on southern and Caribbean plantation zones. Her recent book, The Flood Year 1927: A Cultural History (Princeton UP, 2017), examines how the most devastating, and publicly absorbing, US flood of the twentieth century took on meaning as it moved across media platforms, across sectional divides and across the color line. It was recently awarded the MLA’s James Russell Lowell Prize (Honorable Mention) and ASLE’s biennial book prize for the best book of ecocriticism (Honorable Mention). Her first book, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (UNCP, 2006), is a study of how people in England and in British-controlled America conceived of—and made knowledge about—American nature within Atlantic scientific networks. This book won both Phi Beta Kappa’s Emerson Award and the Jamestown Prize. She has received fellowships from the NEH, the American Antiquarian Society and Harvard’s Charles Warren Center and her teaching at UM has been recognized with the John Dewey Award and the University Undergraduate Teaching Award.

Natalie Lyijynen is a freshman at the University of Michigan double majoring in the Environment and Biology, Health, and Society. She’s passionate about the science behind sustainability and plans to pursue environmental law. In addition, she’s always loved the arts and has further realized her love for creative writing after being a part of the Lloyd Scholars Program for Writing and the Arts. Through the Undergraduate Research Program, she joined Michigan Quarterly Review to help research the global water crisis and solicit for their Spring 2020 issue. Realizing the value of interdisciplinary scholarship in communicating about environmental issues and with the help of MQR, she conducted an interview project. She interviewed five professionals who bridge the gap between the sciences and arts in order to shed light on the barriers faced in work on climate and water issues. Her purpose was to address historical precedents, research how stereotypes have changed or persisted, explore the professional impact of the interviewee’s work on climate and water issues, and gain insight on global trends and what the future may look like for interdisciplinary scholarship.

This interview took place in February 2020. It has been edited for clarity and length.

Natalie Lyijynen (NL) : After World War II, in his essay “The Artist, the Scientist, and the Peace” Sinclair Lewis claimed of scientists and artists that, “Their native land is truth, but no artist or scientist in history has yet dwelt utterly and continuously in that land of truth, because it always has been stormed by the lovers of power.” Thinking about global tensions and political divides, what are your thoughts on this elusive idea of truth?

Dr. Susan Scotti Parrish (SP): What I’m uncomfortable about that quote is that it presumes there’s only one truth— hat there are the good folks that know it and say it and that the power-hungry try to cover it up. This seems too simple to me. One of the things I found really interesting in the archive for the flood of 1927 was to see an event take place where numerous groups saw very differently. What appeared to be truth for one group was not the same truth for another group. Disasters are very interesting sociological phenomena. The stories and how they are being told reveals a lot about the teller. The southern white press, for example, tended to see it as an engineering debacle and unthoughtful agricultural development. They explained it in terms of federal mismanagement and improvident agribusiness in the upper valley. African Americans were less focused on the reason why the flood occurred and more on who the flood affected. I think both are arguably true, and the North had another different view. They saw the event as a natural disaster, and the northerners were the heroes saving the day in the South. I think I’m trained through literary modernists to think this way. Someone like Faulkner tended not to have a third person telling the story as if there was one truth and instead utilized multiple characters as narrators. The reader has to assemble their own collective truth. There certainly are conditions where artists are trying to expose atrocities or scientists are trying to warn of dire effects of human behavior. It’s been a consensus in the scientific community for a few decades about the effects of climate change. Both groups (artists and scientists) are modeling a catastrophic future. Our current president doesn’t believe this to be true – so the quote you read does match this scenario. The most powerful person in our country is questioning what science and many in the arts would say is true. So sometimes it does happen that way, but oftentimes there’s isn’t a unitary truth.

NL: In his essay, “The Scientist as Artist,” Robert T. Lagemann described scientists as “coldly intellectual with an almost complete lack of esthetic sensibility and humanistic appreciation” and artists/writers as mystic and “having a profound sense of imagination and a keen discernment of esthetic values.” Do you think there are still remnants of these stereotypes today? Either in the professional world, or perpetuated in the media?

SP: I don’t see that very often, and I’m partly reacting to scientists on our campus. I teach in PitE and that department is a mixture of natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities. I wouldn’t notice a radical difference between the worlds of artists and scientists. One thing that is similar across them is an evidence-based, or empirical, approach. Either you start with a hypothesis or you start with evidence and draw a theory out of it. What we teach in English classrooms is to approach each text like something that we generate questions out of. If you want to make an assumption, you have to base it on evidence and familiarity with the subject. I think of that as similar to various scientists. They’re trying to be extremely good observers – open to the data presented to them. I don’t know how similar that is to a novelist or a poet because they’re creating something, but I do know artists who care a lot about realistic interpretation. I tend to not think of my colleagues in the sciences as being all that different. What we try to instill in students is a fidelity to what you’re seeing.

NL: In 1965 Blaise J. Opulente described a cold war between science and the humanities. Do you feel that this sentiment still exists to some extent?

SP: At times, there has been a sense that sciences produce concrete benefits for society – lifesaving medical technology or an aqueduct that brings water – whereas the humanities is a softer field. It beautifies the world. That’s a stereotype that I don’t think many scientists would hold. Thinking about it in a university setting, a lot of laboratories actually get their funding from outside the university. I think scientific education is quite expensive and I think the humanities are a little less expensive. We need to have a world-class library system and computing is important, but there aren’t huge start-up costs. We tend to bring in money through our teaching where the sciences bring in money through external grants. I think there’s also a worry that STEM education seems so important in an era of international competition – which has been going on since even before Sputnik. It can seem that the humanities take a backseat. The English major, for example, has gone down in size pretty dramatically in the last 12 years. In an era that is increasingly valuing STEM or a practical major to get a job right out of college, humanities gets misrepresented as an impractical pursuit. This oversimplifies the choices.

NL: What barriers are there in interdisciplinary work on climate and water issues?

SP: There’s a Water Center at the University of Michigan, and they have an annual conference which is highly interdisciplinary. I have seen a lot of productive interdisciplinary work around water issues. In the aftermath of Flint, I’ve watched that resonate across the health sciences and Michigan politics and then certainly in the arts – theater productions and journalistic essays. Let’s say that I was a writer and I wanted to write a fictional account about a water crisis, I think people in the natural sciences or engineering here would be happy to talk to me. They would be happy to talk to people that have a way to imaginatively publicize a problem, model the future of a problem, communicate a problem. I think a lot of people who work on issues of climate change say that it’s not a scientific problem. The data has been in for quite some time. It’s a communication problem to get people to accept the problem and do something – which is more in the realm of human behavior and consciousness. Science still has roles but in terms of bringing about a pivotal behavior shift, there is a need for the arts.

NL: Can you tell me a little about your life and what brought you to science and writing – being a professor in PitE and in the department of English?

SP: It’s more of a historical curiosity that brought me to graduate school – particularly about North America. I prefer to interact with that history by reading documents very closely. People are still trying to understand the Old Testament and Shakespeare. It’s a never-ending investigation. I had this historical curiosity and love of close reading. When I was doing my graduate exams and reading a lot of early American texts, I kept seeing the natural world in the texts. Everyone was trying to understand what American nature consisted of. There was also a sense that divinity communicated with people through the natural world. Nature was in every text that I was reading, and this got me started with thinking about scientific writing. Out of that, I’ve always had one foot in environmental history and one foot in literary history – so PitE made sense.

NL: Thinking about our current global situation and the urgency of climate change: How is your work affected by this urgency? Is that urgency reflected differently in your creative work than in your scientific work in PitE?

SP: In the scientific atmosphere at Michigan, there’s more of a focus on the material. They’re doing the actual research behind climate change and its effects. Maybe there is some physical sighting, but many are seeing it through their instruments. I was listening to a British scientist who has been working in the Arctic year after year. In his case, he literally sees changes. To some, there is this direct observation of a change. For many scientists, they are working through instruments and have to interpret their data. For people in the humanities, we are one step further and interpret scientific writing. The urgency of climate change has affected my work. What motivated my most recent book was an environmental disaster and one can argue that natural disasters are related to climate change. Watching Hurricane Katrina unfold on the media, I wanted to think about other disasters. With an increasingly warming climate, there are going to be more frequent disasters.

NL: Can you start with your experience behind The Flood Year? When did you first read about it, and why did you feel compelled to take it on as a research topic?

SP: I’ve had a long-standing interest in southern literature – particularly William Faulkner. I’ve been reading him seriously for over 30 years, and I’ve also been reading and teaching Richard Wright. Both of them were young men living in the Mississippi Delta or very close to it during this flood. From Katrina, I was more sensitized to thinking about disasters, and I began to realize that Faulkner had written about the 1927 flood and that it had washed across a number of his novels. Richard Wright had written at least one novella about it. He was living in Memphis which was the center of the Red Cross relief. The more I read about the flood, I realized that there were many more writers and artists whose work centered around it. I initially imagined it as a literary history of the event, but reading the newspapers became so fascinating. I became very interested in the stories that different groups were telling about the flood. The Red Cross and Herbert Hoover were managing a narrative in the beginning and the nationwide media was set up during this flood. There can be these very slow disasters that happen in a time of fast media. I wanted to not just think about how people remembered the event years later, but to think about the media history of the event as it was unfolding. I began to see a very different narrative unfolding in the southern white press and the Black national press and the white northern press. What I came to believe is that the southern whites were listened to by northern white readers. The protests and conversation going on in the Black national press didn’t really cross the color line. This happened more in popular entertainment than in journalism – Bessie Smith and her Blues song. My argument was that it was more in entertainment that African American experience was able to become publicly known. There’s been a theory that we work best as a society if we are able to have a deliberative public sphere – not escapist public entertainment, but serious problems. When news starts to become entertainment, it’s bad and useless. This is too simple to say. The New York Times, in my opinion, was telling a false myth about northern rescue, whereas these Black comedians were telling a very true story about their experiences.

NL: The flood of 1927 was the first environmental disaster to be experienced on a mass scale: newspapers, radio, music, etc. Today, being in the digital age, can you talk a little more about the importance of media coverage in emphasizing environmental issues? What’s the value of art and humanities in communicating these issues?

SP: There are people in the science fiction genre who are trying to model out what various cities will look like. You have to bring the consequences of people’s actions to make them feel as if they are already living in these dramatically altered environments to see that what they do will have an effect in 200 or so years. I think artists who can imagine various futures are very helpful. Kayne West spoke out about Hurricane Katrina and the racist oversights or lack of care that President Bush had. I think you have to ask who has access to public consciousness and very often, public artists and figures have this access to shape public opinion.

NL: You compared the 1927 flood to Hurricane Katrina – namely the relief efforts. How would you add to that comparison in light of recent disasters (the global water crisis)?

SP: It was interesting for me to realize that even back in 1927, disaster relief was pouring in from all over the world. It was pouring in from China, from the Pope in Rome, from England. The British Press was covering this event as close as any American newspaper. There was global coverage back in the day. What may be different now is an awareness that we are connected globally. For example, the carbon emissions from the most emitting countries are affecting everyone on the globe. Even in disease outbreaks, there’s a sense of our global proximity to each other.

NL: In your conclusion you wrote, “artists need to interrupt the ways our routinizing minds make comfort out of unsustainable risk. Art must help science in this most difficult kind of inquiry.” Can you expand on this claim and address how you see art and science working together today?

SP: This is an old theory about what art does. We, being creatures of habit, tend to see the way the world is as the way the world must be. Once we do something routinely, we stop being aware of it. One of the things art and humanities do at a big university is to make us all alertly observant. Art does have the power to make us newly aware of things that we thought we already knew. If a painter is painting a seascape, it can make us aware of all of the colors that are actually in waves or what light does at a certain time of day. One of the things that artists are particularly good at is making us observe closely. Because they make it interesting, they make us want to observe closely and see what has become routine. Something that may have become routine for us is driving a car. It’s handy and everyone aspires to own their own car. It speaks of a sense of freedom and art in the past has built up a sense of mystique around the car as being the romance of travel. We come to see the car in a certain way over decades, but once we realize with climate change that fossil fuels are going to drastically change our planet, we should come to see travel and transportation in a different way. Artists could take something that we so routinely accept and make us understand its consequences anew.