A violence that deliberately refrains from enforcing law, and instead…ruptures the homogenous flux of profane time. These rituals resurrected primordial chaos, making humans contemporaries of the gods—Giorgio Agamben

On an unnamed island, things start to disappear: hats and ribbons, birds and roses. No sooner had an object vanished, than the residents intuitively know about the disappearance, pre-ordained by the Memory Police. However, in order not to be persecuted, they do not hide or hold onto the specimen of the object that is still a part of their consciousness. Before the Memory Police can go barging into their homes, incarcerate them and wash them clean of their memories, the residents disappear the remaining specimens in disturbing ceremonies. They gather in small groups to bury away or burn down the things. They dump the remnants into the river, mourning while they do so but without much regret or resistance.

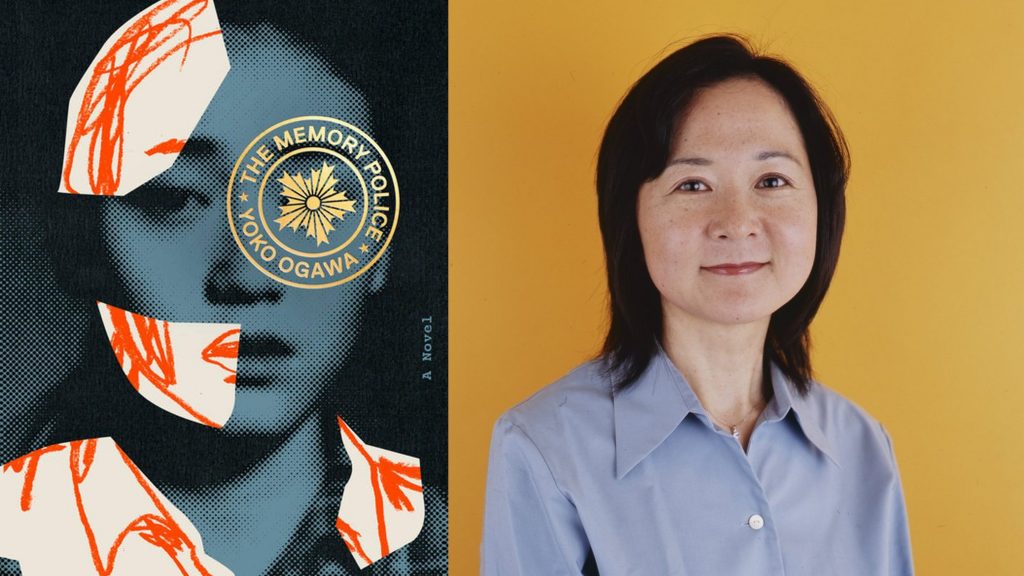

In countries such as the United States and India, the populists of the far right are dominating politics. To paraphrase Hannah Arendt, they are overturning democracies degenerated into ochlocracies (mob rules) into majoritarian tyrannies. Against such a depressing backdrop appears the English translation of Yoko Ogawa’s novel, originally published in Japanese in 1994. The Memory Police is a work of extraordinary artistic defiance, an exploration, urgent and seething, of the abrasive relationship between the role of dissidence in shaping public consciousness and the modern state’s totalitarian proclivities to create a political order founded on the organizational principle of fear.

The nameless narrator-protagonist, watching the winter of disappearances descend on the island, is a solitary and uncertain novelist. When family friends come knocking at her door one freezing night, she recalls the sad and unrequited fate of her mother that she has not been able to forget. A sculptor of tapirs, her mother was endowed with the dangerous gift to preserve things in her memory, and secretly transcribe her memory onto the articles she created, even after they had been disappeared. She died years before in mysterious circumstances while she was held in custody by the Memory Police. Now the head of the family, Professor Inui, who took care of the protagonist during that difficult time, has been similarly summoned and ordered to present himself at the genetic analysis center so that the Memory Police could employ his research in decrypting the genetic codes of the subjects. The frightened family huddles about him, but the protagonist acts:

I went upstairs, heated the milk, and poured it into mugs. Then I carried them back down to the cellar and we made as if to drink a toast, though we were careful to avoid the sound of clinking cups.

It is through countless little gestures such as these that Ogawa pierces the atmosphere of intimidation that the state pervades, registering human ability to survive and celebrate when political repression is not only imminent but inevitable.

Though Ogawa is not heavy on plot, The Memory Police has the pacing and macabre delights of a crime thriller. Much of the novel’s action centers on the shifting dynamic between the protagonist, who is working on her fourth novel about a little girl battling the disappearance of her voice, and the protagonist’s friend and editor, R, whom she is hiding in her storeroom. Like the protagonist’s mother, R is unable to forget. Thus the protagonist embodies the tension of straddling two worlds antithetical to each other; she is a busy conduit between the relics of memory R represents and the quickly diminishing outside world that becomes so surveilled that R’s relationship with his family is completely severed, necessitating a sort of mutilated and faintly scandalous romance between the two. Despite being drawn in by the sensual pleasure while reading this section, I also wondered how could the protagonist be conscious of the specificities of what she forgot while undergoing the process of amnesia? This is not a technical shortcoming or Ogawa’s extravagant use of poetic license. It is precisely this paradox of being reminiscent of the loss of memory, of a consciousness being constantly amputated and, through narration, recreated, that makes the central character endlessly fascinating. She is no sham, but a staggering feat of Ogawa’s literary artifice.

As the Memory Police become more brutal, disappearing things and individuals at an alarming speed, the world of the island shrinks further and further. Even the food inside the kitchens dwindles. But the industrious protagonist creates a small cake from whatever scraps of ingredients she can get her hands on, to heartily celebrate the birthday of an old boatman whose ferry has been disappeared and whom she has dearly befriended. Through the deepening of her central character, Ogawa breathlessly glides us forward, because the life she infuses into the protagonist and her relentless exchanges with the rest of the characters far exceeds the terrors of extinction that the fascist police is determined to inflict.

***

Some scenes jumped at me for their remarkable resemblance with what I experienced and remember of my childhood, those days of constant humiliation and asphyxiating surveillance I lived through in the 1990s in Kashmir. For instance, when the protagonist accompanied by the sweet old man is returning from her mother’s cabin where they have furtively picked up sculptures “which contained something that had [been] disappeared.” Just before boarding the train, they go through the excruciating encounter:

[The Memory Police took] their time examining each person’s identification. They turned over the documents, held them up to the light, repeatedly compared photograph to person, and otherwise checked for fakes, while at the same time matching the identification numbers against their black list.

This scene transported me to the gray March morning when I was on a bus to my school in Kashmir. At the checkpoint, as it began to rain, the soldiers ordered the driver to stop, shouting at my fellow passengers to deboard, asking us to raise our arms skyward, and queue up in the middle of the dirt road. Holding their weapons on their hips, just like the Memory Police, the soldiers wore dark green jackets, heavy belts, and black boots. Their faces were cold, and their gazes were clinical. The soldiers, recruited from different regions in India, belonged to different ethnic groups. But in the eyes of a Kashmiri child, they all looked the same. The Dravidians from southern India appeared no different than the Nagas from Kohima than the Jats of Haryana. As though the soldiers’ absolute control over the Kashmiri body became the sole source of their identity, erasing the peculiar differences in their physical features. As though their limitless power and ability to strike terror uniformly had obliterated their very personalities and rendered them incapable of making any moral decisions individually. These were the same soldiers who came rampaging into our villages and performed crackdowns and night raids. They snatched innocuous boys and young men from their midnight sleep and drove them away in their canvas-covered trucks to the dark, impenetrable prison cells from where thousands have not returned home to this day.

As I neared my turn, a soldier looked at the identity card of an old man standing in front of me. The old man was not fluent in Hindi, the language the soldier in charge spoke. Wiping the rain from his unshaven face, he muttered a few broken words in vain. The soldier slapped him, tearing his identity card, apparently because the old man’s picture, worn and fuzzy about the edges, did not match with his wrinkled, white-stubbled face.

***

Ogawa not only dramatizes the state’s desire to occupy and subjugate the territory populated by willful, rebellious characters, but she goes further and examines the impact the military violence has on the body. At the end, the protagonist is bewildered by the disappearance of her own left leg, the first limb to go.

I pulled back the quilt and made a bizarre discovery—something was stuck fast to my hip. And no matter how much I pulled or pushed or twisted, it would not come off, just as though it had been welded to me. …A chilly sensation lingered in my hands from where I’d touched whatever it was that was attached to me a moment earlier…Since I could not remain where I was indefinitely, I decided to get up and get dressed. First, I put my weight on my right leg and slowly sat up. But as I did, the thing fell with a heavy thud and I was thrown to the floor.

The image is grotesque and truly terrifying and impressed on this reader the extent to which the tentacles of the state penetrate and disintegrate the body—the territory the state ultimately wants to occupy and possess.

***

I finished reading the book in December of last year when the news channels reverberated with Donald Trump’s insistence to build his beautiful wall, a testimony to the President’s resolve to offend the dignity and attack the rights of immigrants and refugees. At the same time in India—and this was three months after snatching the land rights of Kashmiris and locking up the entire population of seven million mostly Muslim residents in a throttling and what in modern history of humankind would become one of the most prolonged and comprehensive siege—the Hindu supremacist ruling party, which enjoys a mob-like majority in the Parliament, legalized the Citizenship Amendment Bill. The bill that brazenly discriminates against Muslims South Asian immigrants was institutionalized to further ghettoize the two hundred million Indian Muslims who, on the pretext of producing documentary evidence and birth certificates to prove their loyalty, are being prepared to be quarantined like cattle in the detention centers the state has already built.

In a realm lured by a bigot who prophesies severe punishment for the powerless, promising his frenzied electorate a future studded with sacred, spectacular skies of gore, in a realm swayed by the god-like glory and intoxicating rhetoric of a rabble-rouser, Ogawa’s distilled prose prefigures the erosion of the values that constitute democratic culture. The Memory Police is a disturbing revelation about the very muck we inhabit. But to have been able to realize such a dystopic vision, enforced imprisonment and brutal torture and custodial murders, the loss of limbs and the loss of privacy and the loss of individual freedom, with such ingenuity, tenderness and control, makes this writer no less than a prodigal performer.