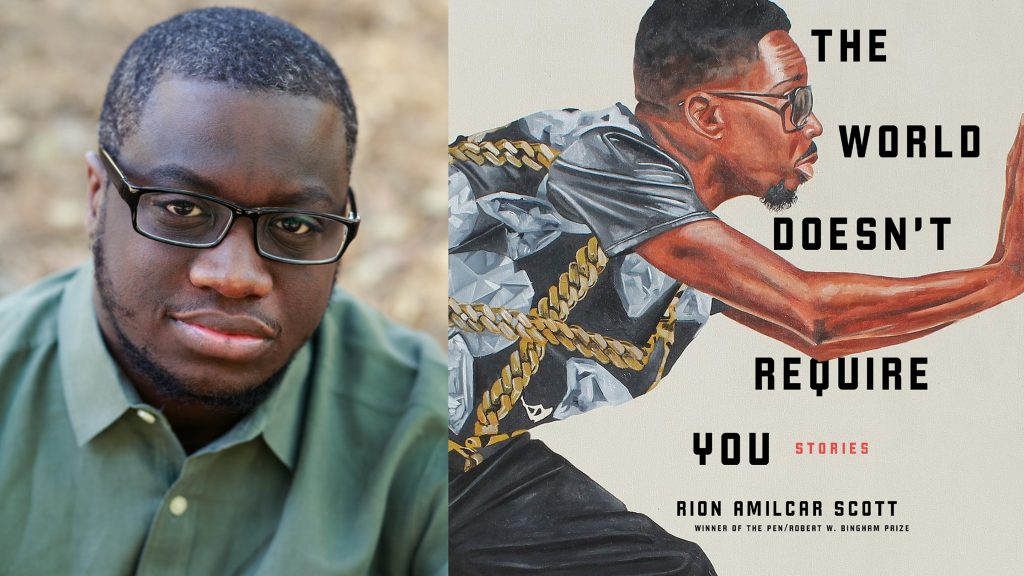

Rion Amilcar Scott’s story collection, The World Doesn’t Require You (Norton/Liveright, August 2019), shatters rigid genre lines to explore larger themes of religion, violence, and love—all told with sly humor and a dash of magical realism.

Scott’s debut story collection, Insurrections (University Press of Kentucky, 2016), was awarded the 2017 PEN/Bingham Prize for Debut Fiction and the 2017 Hillsdale Award from the Fellowship of Southern Writers. His work has been published in journals such as The Kenyon Review, Crab Orchard Review, and The Rumpus, among others. One of his stories was listed as a notable in Best American Stories 2018 and one of his essays was listed as a notable in Best American Essays 2015. He was raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and earned an MFA from George Mason University where he won both the Mary Roberts Rinehart award and a Completion Fellowship. He is currently a Kimbilio fellow and lives in Annapolis, MD.

This interview was conducted at the University of Michigan and has been edited for clarity and length.

Kashona Notah (KN): First things first, I wondered if there are any questions that you’d like to be asked about your work? Things that you’ve wanted to talk about in the past but haven’t had a chance to yet.

Rion Amilcar Scott (RAS): I don’t know, I’ve been asked a lot about the evolution of the town, and how it’s come about. I don’t have a good answer to that. The only thing is, the things that I’m currently writing, I feel are always going to be about Cross River. I see it as an arc that I’m trying to follow, and so hopefully one day, it’ll be done, and I will have written the entire Cross River Saga.

KN: In reading your work, I thought there was something that was quite liberating about the way you approach the arts. For example, you give your reader enough to understand what Riverbeat is, what the stakes are for the characters, but you also give the reader a lot of freedom to imagine. Starting with “David Sherman, the Lost Son of God,” and maybe following with, “The Temple of Practical Arts,” I wondered if you could speak to music in your work, and perhaps on a greater level, also to art across mediums and how your work is in conversation.

RAS: In terms of music, it’s something that has always been inspirational for me. I don’t listen to music when I write, but the rhythms of music are always there. And if I’m not listening to music, my writing just doesn’t have that pop or rhythm to it. It’s important to me to engage with music. I’m not really trying to define a specific music. Riverbeat sounds however it sounds for the reader. There are certain elements: the scatting, the part in the songs where they play the notes backwards, and the drums, which are important, but however that sounds to the reader, however they put those elements together, is how they put them together. I want to give readers room to be imaginative within the space of my stories. We’re cocreating a story together as writer and reader.

KN: Do you have authors you feel were an influence or inspiration? Are there things that you were reading in preparation for, or while writing The World Doesn’t Require You?

RAS: Yeah, there are a lot. I think that The Women of Brewster Place was something that was important, especially early on, when I was developing the concept of connected narratives. Edward P. Jones. There were a lot of sentences that wouldn’t exist if Edward P. Jones’ sentence structures hadn’t existed. Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg Ohio was really influential to me. As a writer, I’m constantly picking and pulling from different sources and places. So, it’s daily. I’m reading a poem every day now, just to get the rhythms, just to get the fluidity of language into my work.

KN: Kind of also going off of the world building element of Cross River, in an interview for Literary Hub, you described a transition, a realization that Cross River was a returning character for you. Cross River became the character, which I thought was so cool, and I wanted to ask you what that transition was like?

RAS: That’s a recent revelation for me. I had this one character, Kin Samson, who was in the last story of Insurrections, and is in the last story of The World Doesn’t Require You. I always thought he’d be my reoccurring character. He’s a character I created a very long time ago, for very different purposes. I created him in undergrad in a scriptwriting class. And I wrote a screenplay where he was a sort of an analog of me. But the character moved further away from who I am as a person. And when I first wrote him in Insurrections I thought the story was going to be about him. That story took me about three years to write. And it was very, very difficult, but the story became easy to figure out once I realized the story was actually about his father. Kin is more of a framing device– he’s in the beginning, and he’s in the end. But the middle of the story is the father talking. So, I believe Kin narrates a little bit, but he’s not as important to the story.

When I was writing The World Doesn’t Require You, again, it was natural for Kin to be there in the scenes that he was in. But he became even less important as revision went on. There were certain parts that were better for the student adjunct. So, the adjunct became a more fully developed character. And it made more sense for her to be saying things Kin once said. I had to rewrite it for her to be addressing the subject and the narrator. It was sometime after that that I realized that there was some reason why his character kept minimizing himself every time he appeared, and I think it’s because Cross River is my actual reoccurring character.

I also remember reading Junot Diaz’s Drown, and all three of his books for adults for that matter. Yunior is very important to all of them, and I really loved how Yunior is in Oscar Wao. And I was like yeah that’s how Kin is gonna be, Kin is my Yunior, but Cross River is actually my Yunior.

KN: Cross River is largely defined by its history, as a site of a successful slave rebellion, the Great Insurrection, the city takes on a particular existence. In “The Electric Joy of Service,” and “Mercury in Retrograde” the robots are inspired to rise up against their masters by that history. The stories create a futuristic imagining of slavery, one that is closely connected to the past. I wondered if you could talk about the connections between past, present and future within your work.

RAS: It’s funny, when people talk about the “The Electric Joy of Service” and “Mercury in Retrograde,” it doesn’t say anywhere in them that they take place in the future. But I think that in real life, we’re always wrestling with the past, and we’re not even thinking about how we are wrestling with the past. So much of what we do is based on traditions. Often, we don’t even know the origins of those traditions and they’re essentially dead metaphors. Sometimes it doesn’t matter, but sometimes it’s important to actually think about where these things that we do come from. Sometimes the things that we do are because some rich person had a marketing campaign years ago and said that this is why you should eat this for breakfast, and we do it without really thinking about the consequences. And I’m just like everyone else. I want to think about how the past affects us is in known and unknown ways.

Also, when we’re making the decisions we’re making today, we’re very short term in our thinking. We’re not thinking about how we are affecting the great-grandchildren that we’ll never see. And it’s very much how we got into the situation we are in with climate change, and the destruction of animal’s habitats, and all that stuff. Because people making decisions years ago didn’t think about right now. And we sort of perpetuate that. So, a lot of what people in Cross River are dealing with is very much affected by the past. The past is a living thing in their lives, and they always have to decide whether they are going to betray this legacy that’s been bestowed upon them, as the children of the Insurrection, or if they are going to accept it.

KN: You were just talking about future generations and I was actually going to ask you: How do you find writing as a parent? What are you thinking about that you may not have considered otherwise?

RAS: It’s really interesting. When I started putting together Insurrections, I wasn’t a parent, and by the end of putting it together, I was. And I think that some stories, a lot of stories, are parent stories. They’re father and son stories, or father and daughter stories. But even before I was a parent, I was interested in this. I think there are a lot of stories that I would have written differently if I had been a parent. Being a parent gives me a lot more compassion for my own parents, and the sacrifices they had to make, and what they went through. And with a story like “Confirmation,” I probably would have written it a little differently. As a matter of fact, I think I started “Confirmation” before I was a parent and finished it afterwards. So yeah, I think that sort of influenced that story. This newfound compassion I had influenced that story, a lot. Come to think of it, yeah, it influenced that story a lot. And you know, I think that being a parent is interesting because it gives you a lot more ideas, but a whole lot less time to enact those ideas. It really influences my perspective, especially when I’m writing about parenting.

KN: In your new collection, with stories like “Numbers” and “A Loudness of Screechers” you incorporate the magical. Which is kind of going further than the last collection– going into the speculative, fantastical, and magical realm. What were some of the reasons you chose to go in the direction of the mythic and speculative?

RAS: I think the first and foremost reason is fun. It’s fun to write those things to me. I think secondly, it really allows me to dramatize some ideas that I can’t dramatize otherwise. Thinking of “Numbers” for instance, I can really dramatize ideas relating to toxic masculinity and sexism, giving it some distance, but still making it recognizable.

KN: I’m always interested to know what an author’s journey to literature was. Did you always know you wanted to be a writer? And could you tell us a bit about your formative years? Perhaps more specifically, tracking the transition from reading and consuming literature, to creating it. Kind of your journey as an artist.

RAS: As a kid, I always loved reading. Going to the library and schools was always fun to me. And I was always doing something creative. I was making up stories. I see that now as a precursor to writing stories. And I think at a certain point when I was a kid, I became really interested in poetry. It dawned on me one day, that I could do this thing, I could write poetry. I don’t know if I ever really thought about it previous to that. I remember reading a lot of Langston Hughes when I was in elementary school. And reading various other things. When poetry dawned on me, I just became sort of obsessed with it. I was writing constantly, and reading a lot of poetry, and it became a serious thing, and when I started writing I knew that there was nothing else. I found my path in life. But when I went to college, I thought that I needed to do something practical, and I became a journalist. It didn’t click for me though, I still know, understand and respect the importance of journalists, and still keep that identity in some ways, even though I don’t practice journalism, but it wasn’t what I needed. It still informs what I do as a writer, but I sort of needed to break free from that. So, I started writing fictional stories. And I left poetry behind. All that stuff forms a basis of what I do though. I’m not a poet, but poetry is so important. It’s my language, and I have that foundation. I’m not a journalist anymore, but that really does inform me, especially its modes of inquiry.

KN: So, what are you reading now, and what are you excited about?

RAS: I’m reading this graphic novel called Rusty Brown, which is sort of blowing my mind. It’s really strange. I’m reading a lot of stuff now. Amber Sparks’ And I Do Not Forgive You, another short story collection, which is really, really good.

What I’m excited about. I don’t know, just waiting to see what comes down the line. You never know what’s gonna be the book that’s gonna blow your mind. I wasn’t really aware of Rusty Brown. I think I might have seen it here and there, but I probably wouldn’t have picked it up if it wasn’t nominated for an award. So, I was interested in it, and after reading, I was like wow. So, I don’t know, just waiting to see what’s coming down the line.

KN: Do you have any advice for aspiring writers?

RAS: One of my professor’s, Alan Cheuse, used to say, read as much as you can, write as much as you can, live as much as you can, in that order. Which I think is really good advice.

KN: That is good advice. Final question. What’s next for you? Do you have any projects or goals that you’re willing to share?

RAS: Yeah, I’m working on a novel, another Cross River book. I think my biggest goal in life, other than making sure my children turn out to be good people, is finishing the Cross River Saga.

Kashona Notah: Nice. I appreciate talking to you. It’s been a pleasure.

Rion Amilcar Scott: Thanks for taking the time.