Keisha Knight-Pulliam, best known as Rudy Huxtable from The Cosby Show, will make you weep in the Little Match Girl. Especially if you are seven years-old and you haven’t yet read Hans Christian Andersen’s story of the little orphan urchin. In 1987, Knight-Pulliam was enjoying a moment in the sun as one of very few black children on prime-time television when she was cast as Molly, the homeless sprite with an entrepreneurial streak and a Pollyanna spirit, in the The Little Match Girl. I watched the made-for-television movie in my parents’ bedroom, wiping away the tears streaming down my face, wondering how a Christmas movie with Rudy could be so devastatingly sad.

Thirty years later, my own children are around the same age as I was when I bawled at a match girl. My children are half-Asian; I’m white, my husband is Korean. My children rarely see mixed race children represented in American holiday films, and this is nothing new. Hollywood has historically been among the worst industries for representation.

Progress peeks through. Malaysian-English actor Henry Golding stars in this season’s Last Christmas. Netflix released The Holiday Calendar last year, featuring a biracial woman as the heroine, and The Princess Switch with a panoply of different ethnicities represented among the lead characters. Representation isn’t all that matters, though. The American Holiday film is both a genre and a multi-million dollar growth industry. It’s a cultural tradition, and a means of telling our stories. But for too long the roles available to People of Color have been symptomatic of much more insidious diseases in our country.

Upon revisiting the film, The Little Match Girl, I realize how unfaithful to Andersen’s story the movie is. Directorial decisions to diversify a cast aside, these departures go well beyond artistic license to make a story more relevant. The Knight-Pulliam version is set not in Andersen’s Denmark but in a mythical turn-of-the-century America when streetcars moved alongside horse-drawn carriages and girls said, “Isn’t that just grand!?” with no sense of irony. Andersen’s story, only 11 paragraphs long, still spares enough real estate to mention that the orphan protagonist had “long fair hair, which hung in pretty curls over her neck.” Knight-Pulliam’s twisted braids in The Little Match Girl are darling and reminiscent of her role as Rudy Huxtable–no doubt a sure bet for marketing the film by riding on the coattails of The Cosby Show’s success. Other than the protagonist’s predicament at Christmas, the original story and the 1987 film have nothing in common. The film has none of the tragic marks of the literary tale, and weaves in a complicated story-line about a real estate tycoon and forbidden Catholic/Protestant marriages. Importantly, though, the film dumps us out on other side of the rich old white man’s epiphany about the real spirit of Christmas. This occurs, aptly, right after Knight-Pulliam strikes her magic match and smolders the wicks of all our hearts with that wide, pearly grin. “Magical Negro” much?

Oh, the “Magical Negro” trope has a field day in American holiday films. It appears that the holiday film genre was made by and for white people, as was the “Magical Negro” trope. Director Spike Lee, who coined the term “Magical Negro,” might disagree that Knight-Pulliam’s character fits the true “Magical Negro” mold, since she is the protagonist, not merely supporting the white protagonist’s self-improvement. Also, she is not old, per the “Magical Negro’s” contract, impressing the finicky white protagonist with wisdom born of long-suffering and experience. Still, Knight-Pulliam’s Molly the Match Girl is arguably the quintessential “Magical Negro,” perhaps the touchstone of “Magical Negros” for all the holiday films produced during in the same decade. It’s as though she always was and always is an other-worldly mystic, whose mid-winter survival as a homeless child appears to be secondary to her higher purpose in helping white rich people come to their senses about what really matters, with the simple strike of her magical cardboard matches.

It’s almost laughable if it weren’t all so sad.

Enough tears have been shed over Lifetime movies and Hallmark Holiday films to fill the oceans. But we should all genuinely lament that there are so few People of Color in American holiday films. A keener cultural critic could address the homogeneity in entertainment overall, but the lack of diversity in this particular genre is deeply problematic. The POC problem in holiday films is a reflection of our cultural concept of those deserving, a population for whom American Christmas bestows its rightful joy.

To understand why the holiday film genre is so flawed, we need to acknowledge that it is an American byproduct within a growth industry. The American Christmas movie may typically draw inspiration from literature, but its roots are in a particular prosperity belief system spawned from American consumption. The American Christmas movie is the residue of the American prosperity holiday that lavishly bestows its best gifts on a narrowly selected population. We can trace this holiday, which smacks of American exceptionalism in all the worst ways, well into the last century.

Despite our country’s puritanical roots that decried the celebration of Christmas and its excesses, Christmas made a comeback in the U.S. since the 1830s, according to essayist Russell Belk, who has written widely about materialism and the American Christmas. The return of Christmas to American soil, marked by a wintertime celebration of feasting and family togetherness and handmade gift giving, coincided with the arrival of more and more immigrants from the very countries who gave us the great and enduring Christmas stories: Great Britain, the Netherlands, and Germany. Great Britain’s Charles Dickens gave us the immortal A Christmas Carol in 1843 and Denmark’s Hans Christian Andersen set The Little Match Girl on the literary shelf two years later. From these two stories’ themes of impoverished characters finding wealth in family togetherness do many holiday film narratives derive. Given the swell of immigration in mid-1800s America, where many new immigrants were struggling just to survive, this makes sense why these stories would “stick.” This is not to say that Native American, African, or any other traditions were null and void in the young United States. It’s just that of the books published and translated and sold in the U.S. during this time, the most popular were largely a homogeneous blend of Western European exports.

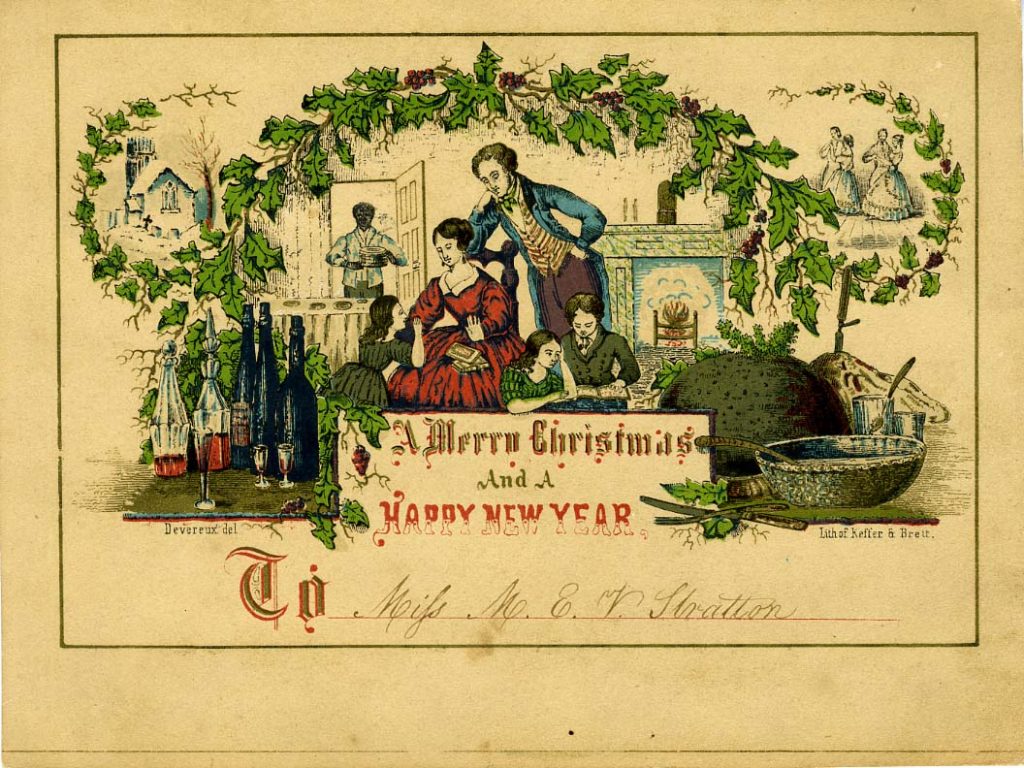

Dickens, and the American writer Washington Irving, seem to have stirred up a particular sentimentality around Christmas. Irving’s essays about yuletide in his collection, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., introduce St. Nicholas as the character who has become our American iteration of Santa Claus. Both Dickens and Irving tie the holiday to Victorian celebrations of home, family, and children, according to Belk’s essay “Materialism and the Modern U.S. Christmas.” Gift-giving on December 25 soon became a way for second and third generations to mark their acculturation to America–whether their families were Christian or Jewish or neither. It’s important to note that English immigrants to the U.S. appear to have held back on the gift-giving of Christmas, recognizing it as a time to give generously to the impoverished, to servants, or in the antebellum South, to slaves. Christmas in the 1800s was, for many first-generation Americans and their children, a time of gift-giving for those they deemed less fortunate.

What I couldn’t ignore in tracing the emergence of Christmas as a consumeristic holiday was the nexus of specific Christmas marketing campaigns after a significant event in U.S. history. Shortly after slavery was abolished in 1865, an interesting trend began in periodicals published in Philadelphia and New York. Historians note that specific marketing campaigns began to appear offering ideas for “Christmas gifts” in the early 1870s. Macy’s launched its first Christmas window displays in 1874. The following year saw the first evidence of Christmas cards exchanged in the U.S.. Christmas commercialism, wherein gifts were no longer handmade but manufactured, sold, and given with the holiday spirit in mind, saw its advent within ten years of slavery’s abolition.

Perhaps there is no correlation. Perhaps some assistant manager at Macy’s decided that they were going to gussy up the windows to chase away the winter blahs and the tradition was so beloved that it continued. Maybe Americans had enough wooden spoons to go around and desired something flashier to give one another at Christmas. Still, if I were to conjecture why the surge in Santa, why the sudden popularity of purchasing in the name of Christmas, I could not ignore that the emancipation of all men and women from the shackles of slavery occurred just as window cleaners were beginning to shine up the glass at Macy’s. Seminal legislation freed a whole demographic of the U.S. population (free in at least one respect, though discrimination persists) and now we have Christmas presents! The employable population is swelling like never before, and how handy that we are in an industrial age when bodies are needed to build the railroads and crank out some clothes with the fancy new sewing machines. God rest ye merry gentlemen–or don’t since we need to stimulate the late 1800s economy. Let’s celebrate this great equity with a workforce gone full-throttle in the North. Christmas for all who can purchase it.

In the U.S., we wassailed into the 20th century, equipped with our Christmas stories from Western Europeans and our Christmas commerce. Enter the holiday film. A respite from wartime, a balm for the world-weary soul, the holiday film emerges to adulate the enduring goodness of the Christmas spirit. The two films in the American holiday genre that emerged early as the most popular of the era are Holiday Inn (1942) and White Christmas (1954). White Christmas indeed. If Bing Crosby, who stars in both films, isn’t singing in blackface as he does in Holiday Inn, he is nostalgizing the minstrel shows which so often lampooned African-Americans. These films offer artifacts of our American film heritage, inventing a coziness and togetherness of Christmas with a dash of entertainment that is apparently only available to and enjoyed by white people. Pay no attention the Mamie character in Holiday Inn, the servile black woman with no known surname, who is more caricature than a three-dimensional character, who only exists to hustle her children in and out of scenes and stare slack-jawed at these glitzy white people.

One of my favorite Christmas movies, Miracle on 34th Street, with a young Natalie Wood, is especially charming in its focus on the belief of children in the authenticity of Santa. Natalie Wood’s character, Susan Walker, naturally gets what she deserves in the end, because of her fervent belief in Santa. The film was remade in 1994 with a lispy Mara Wilson playing Susan. Susan persists in getting what she deserves, because of her fervent belief in Santa. She is also a white child deemed deserving by Hollywood of everything her heart desires. The time-span between the two Miracle on 34th Streets is 47 years. The number of American Christmas movies produced within this same time-span that spent more than a week in theaters wherein non-white people get what they want is practically null. Entertainment writer Olivia Truffaut-Wong has written, “If we believed the movies, then people of color would never celebrate Christmas.” Latinx Americans, Asian Americans, Black Americans, Native Americans and Americans who identify as mixed race comprise roughly 40% of the population, but unless you are Atlanta-based film producer Tyler Perry and you are starring in your own A Madea Christmas, the American holiday film assumes you’re off-camera.

My husband, raised in Canada by two parents who emigrated from South Korea, has only begun to make his way through the canon of American holiday films due to our children’s desire to watch The Grinch and A Christmas Story and Charlie Brown’s Christmas. I cringe when I think about the Asians depicted in the 1983 cult-favorite A Christmas Story, shot in my hometown of Cleveland, Ohio. The Chinese restaurateurs are infamously open on Christmas Day, cooking up a roast duck that smiles at the character of The Old Man, singing “Far Ra Ra Ra Ra!” because they cannot pronounce their L’s correctly. Where else are People of Color portrayed as far outside the margins as when they are featured in a holiday film Doing It All Wrong? It’s your standard issue white normative Christmas baloney, and we can do better.

When I think about my family of origin, overwhelmingly white, holiday films are an easy and fairly neutral conversation topic. We all have favorites and guilty pleasures and movies we watch again and again whilst wrapping Christmas presents. We don’t generally have to question whether holiday films are for us. Or if Santa is for us. Or if Christmas, as a marketing-driven gift-giving concept is patently made for us. Of course it is. It always has been.

This is the lie we buy again and again. That the abundance of Christmas is marked most accurately by gifts bought and gifts given, and that the prosperity of this holiday funnels right into the laps of white people for whom Christmas as a holiday of consumption was always preferential. Keisha Knight-Pulliam strikes her magic match. Cue the tears. Roll credits.

For more writing on the blackface in Holiday Inn, read Kevin O’Rourke’s “Fred Astaire and the Blackface Talking” on MQR Online.