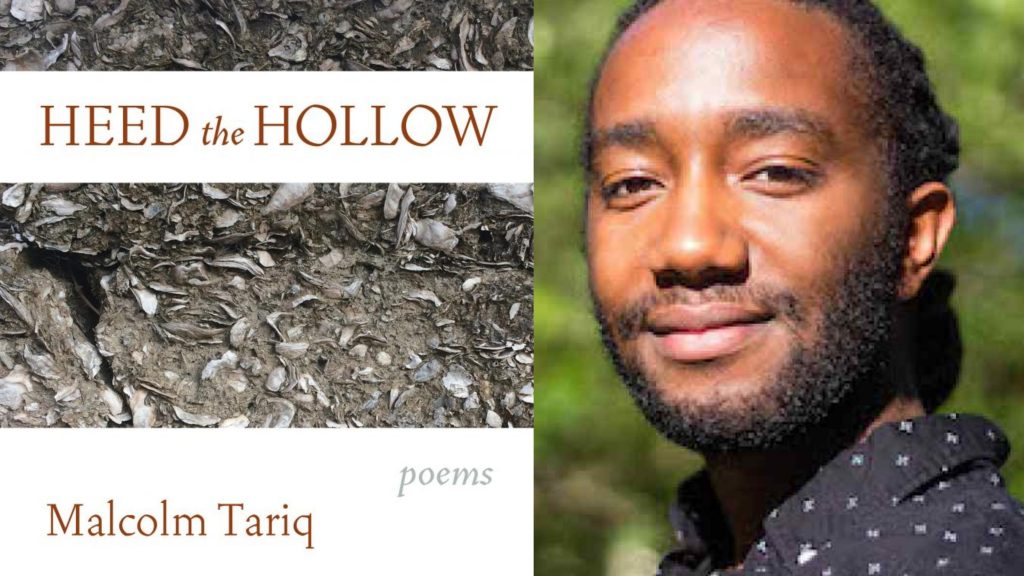

Malcolm Tariq’s wrenching debut collection Heed the Hollow (Graywolf Press, 2019), remaps the American South through the lens of blackness, queer desire and the bearing of witness. In some ways, the collection’s body of work is deeply documentary; it probes not only the brutal histories of enslavement entrenched in land, but the self’s own reckoning with a language of “the bottom.” In Heed the Hollow, language itself becomes a method of documentation. The collection’s formal variation and its astute attention to wordplay create a kind of documentary poetics made visible through the breaking and reassembling of language. As Carolyn Forche writes in her introduction to the anthology Poetry of Witness, “The narrative of trauma is itself traumatized, and bears witness to extremity by its inability to articulate directly or completely…Because the poetry of witness marks a resistance to false attempts at unification, it take[s] many forms.”

Through a series of bops, erasure poems, and a long cento, Tariq mimics the movement of memory through syntax and form. The beginning poem, “Power Bottom” launches with the speaker’s childhood memory in church:

we said Satan, get thee behind

(5)

and I always laughed. A demon child

with a twisted mouth,

at supper time I refused meat

to suck on bones.

This opening confession sets a kind of precedent for the role of wordplay in the collection. The juxtaposition of a poem entitled “Power Bottom” unfolding in church marks the ironic turn of language that creates a form of documentation predicated on humor. To document becomes to rewrite, to make possible the presence of double entendres. The slanting of language is visible even on the level of lines themselves; the enjambment following “A demon child” creates space for naming to briefly exist untied to a subject.

From the collection’s opening “Power Bottom,” to the reversal in the concluding piece “Bottom Power,” the concept of “the bottom” is both how we enter and exit the collection. The inheritance of shifted language creates a space where the past, present, and future all converge. Bearing witness becomes not an act of documenting the present, but an understanding of the claustrophobic proximity of the past. In “Addendum,” the poet recalls a fifth-grade history lesson:

The teachers confirmed what we thought we had known, that we didn’t know/ about such crop, about such labor—we were too city. They used our awe to teach/ a lesson: the terror of slavery, picking cotton is something we would never know, / and this is why we should behave, they sneered, heeding only our bad behavior./ They didn’t tell us how history is never so much the past as it is a condition/ that follows us.”

(75)

The twisting of the verb “to know” into the present perfect “we had known,” the past “we didn’t know,” and the conditional “we would never know” mirrors the slanted pulling between the past and the present. Language enacts witness.

In “Bop: Black Queer Southern Studies,” the song refrain “I believe, I believe I’ll go back home,/ grindin business in my hand…” visually disrupts the poem (9). Yet in these spaces of disruption, a new form is created. By transcribing the tune as a series of repeated couplets, “Sissy Man Blues” is braided into the structure of the poem. Following the first instance of the refrain, the syntax of the line “I don’t hate the South, I hate its longing […]” begins to feel strangely familiar. By mirroring the structure of the song’s refrain, the succeeding lines inherit, and are shifted by, this subtle rhythm.

While the line’s lineage is made visible, the inheritance is never exact. Instead, what is accomplished is an intentional reworking of language. In the first of the “Malcolm Tariq’s Black Bottom” series, every stanza both revolves around, and is punctuated by, the word “cake” (12). In this bizarre and hilarious universe, a version of the word cake can be repeated 42 times and still perform a slightly different role each time. Cake as body:

the bounce

of the Little Debbie

cake

subtle stretch

marks of it makes a Zebra

cake cake

Cake as desire:

cake cake

as wished on the Moon

Pie as wanted by teeth

tongue when upside down

cake

feast for days

cake cake

feast for eyes

And finally, cake as power:

you cannot have

cake cake

although

you may eat it

The lack of punctuation along with the breaking of lines initiates a cyclical pattern. The lines “although/ you may eat it” function both as an end and a beginning, prompting a non-linear reading of the poem.

In “The Body Politic,” the speaker continues to catalogue language: “…I stay stating my name/ like it matters: I am and I am/ and I am—.” (38). The insistence on “I am” haunts the collection: “I am searching for freedom,” (28) “ I am this studious—furthering/and furthering and furthering,” (24) “—I am a body/tied to a body tied to addendum.” “I am and I am and I am/ not this singular being.” (68). The collection creates an archive of being, a catalogue of the precarity of existence in a black, queer body. To bear witness is to insist obsessively on the present tense “I am.” To bear witness is to insist obsessively on language, on its molding, on its recreation.

The collection’s two erasure pieces “Self-Portrait as George Washington’s Teeth” using Washington’s Will and Testament, and “1 Yearning” using reports compiled in Ralph Ginzburg’s 100 Years of Lynching, push against the authority of historically documented language. In both cases, the brutality of documentation is made visible in the process of dismemberment. As the usage of the self-portrait suggests, it is only through the breaking of language that one can truly bear witness.

In “Cento in Which the Narrative Precedes the Lyric,” the coopting of language is placed into question: “This is a matter of ethics. It is a matter of unmaking meaning” (77). By creating a cento that documents only itself, the inheritance of poetic form is interrupted, effectively interrogating the distance between poetry and documentation:

If poetry is not testimony, then what is?

If poetry is not a record of the impossible, then what is it?

Sometimes narrative is all we have.

Sometimes narrative is all we are given.

Tariq’s Heed the Hollow is a humorous, erotic, and stunningly heartbreaking engagement with a language that has forcefully made queer black bodies and voices invisible. Through a steady interrogation of witness, this collection extends documentary poetics downwards: into land, into the bottom of a language and history that has left so much eternally unburied.