This piece originally appeared in the Spring 2015 edition of the Michigan Quarterly Review and is available via our archives.

We stormed the abandoned railroad station in the city to play As You Like It set in the Summer of Love. We wore bell bottoms and painted our faces. We entered to Hendrix and “Purple Haze,” tossing roses to the lovers on picnic blankets. We yelled the words of the Bard over the pandemonium of freight trains, the blues festival thumping down the street, the demolition derby. All the world’s a stage, cried melancholy Jaques, more melancholy still when loudspeakers ecstatic at the crash of cars drowned out The Seven Ages of Man. We leapt in hippie costume off the stage to chase the teetering drunks away from the baby carriages in the crowd. We spied on the crowd behind the curtain, and somebody said: Why aren’t they laughing?

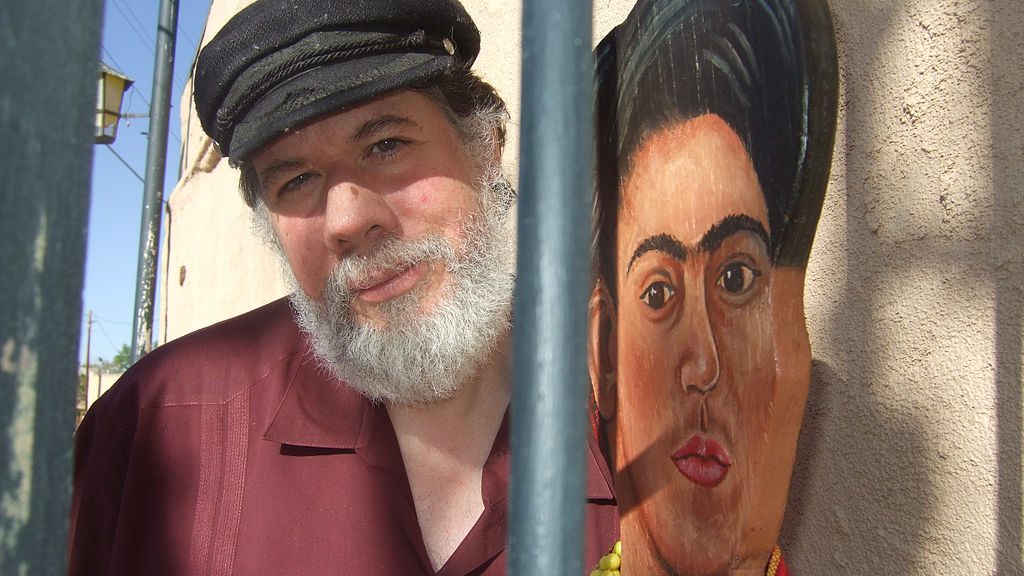

I was Charles the wrestler. I would wheeze my lines like a man punched in the throat, a tribute to Anthony Quinn in Requiem for a Heavyweight. I wore a rhinestone belt across my belly that said Champ, dragging my leg in a brace offstage to kick down a stack of aluminum trash cans, the clamor of their collapse simulating defeat in the match with Orlando, the hero strutting through the play, who couldn’t puzzle out that clever Rosalind was a girl dressed as a boy, teaching him how to woo her. My son was Touchstone the clown, smacking Corin the shepherd with a rubber chicken till the vegans protested the abuse of the chicken, flinging a dozen rubber snakes in the face of William the country boy till the vegans protested the abuse of snakes, squirting a plastic flower at everyone and offending no one, since the flower would backfire and the water would darken his pants. The director’s half-blind dog barked whenever Silvius the shepherd chased the spitting Phebe through the lovers on blankets, the baby carriages, and the drunks, who cheered the loudest till we drove them from the Forest of Arden.

Today is my fiftieth birthday. The company storms my house to celebrate like the brawling Shakespeareans they have seen in movies. On the way, they stop to raid the liquor store, pirates plundering a merchant ship to carry off every last bottle, singing pirate songs. Enter Touchstone the clown, melancholy Jaques, William the country boy, Orlando the hero, clever Rosalind, Corin and Sylvius the shepherds, Phebe spitting at everyone even out of character, and Phebe’s mother, wheeling her creation through the door: Marshmallow Rice Krispie Treat Machu Picchu. I anticipated a pound cake with one candle, not this homage to Neruda and his epic, this place of pilgrimage high in the Andes served up as a blasphemous and crunchy snack. Centuries ago, laborers raised tons of stone without the wheel to build Machu Picchu; Pizarro and his army of conquistadores missed it, leaving the stones untouched. Now, hands snap towers,crack walls, wreck temples, stuffing sticky rubble into mouths. Marshmallow Rice Krispie Treat Machu Picchu lies in ruins.

The sugar is the ember of a cigarette flicked into the combustible sewage of beer, wine, and rum. Soon, William is on all fours in the bathroom, emptying his belly inches from the toilet, pink foam bubbling on his lips like the bubble reputation even in the cannon’s mouth; Sylvius staggers across the living room to escape Phebe, banging into a bookcase, scattering the balsawood egrets of Nicaragua at his feet; Corin clutches a pillow in the bedroom, eyes like the eyes of a praying mantis, left alone by Rosalind to watch a DVD of The Crucible, moaning: How does it end? They can’t do this! They can’t hang these people!

At 5:00 am, the director rises in the kitchen to announce that she will fly everyone to Paris, and the grand gesture of her arms weeps Touchstone’s sushi plate to the floor, smashing it to shards. Actors dangle from couches and chairs. They may not be breathing. A stranger with a Great Dane forages through bottles in the back yard. The beast whines and sniffs the air; the Forest of Arden is burning.

I am fifty years old. I am hiding. I lock myself in the room where I write, surrounded by the smoke-damaged books of poets long gone to oblivion, sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.