Anyone who works in medicine, or who has witnessed a medical procedure, knows that the marvels of modern medicine come with various prices. One of which is trash: many medical tools and devices, like syringes, are used once and then thrown away. And each of these tools is packaged individually, in sterile plastic packaging, which is also discarded once it’s been opened. For example, during my son’s birth in 2013, while my wife was laboring away, I watched in awe as her nurses opened and threw away item after item after item. I couldn’t believe how much trash we produced simply by coming to the hospital to have a baby.

Specifically, I couldn’t believe how much plastic trash (which everything was made of) was produced that night in Pennsylvania Hospital. At the time, I was writing my first book, As If Seen at an Angle, which includes an essay about plastic vis-a-vis my late mother’s chemo port; admittedly, I had plastic on the brain. And I was thinking about how doesn’t degrade, not really; plastic’s half-life is estimated to be anywhere from about 500 years to infinity. Therefore the trash bags we filled that long night in the hospital became semi-permanent, if not permanent, mementos of the experience we’d had. Somewhere, likely jammed in a landfill in New Jersey, there’s a (plastic) bag of (plastic) hospital trash standing witness to the night my son was born. It will outlast us all.

***

Plastic Anniversary, the latest record from the long-running electronic duo/couple Matmos (Plastic Anniversary is their 10th solo release), is entirely derived from plastic detritus, objects, and instruments, and casts a gimlet eye on its source material. Matmos have made a career out of musique concrete-esque composition—their last album, 2016’s Ultimate Care II used sounds produced by the washing machine of the same name, and 2001’s A Chance to Cut Is a Chance to Cure famously used the sounds of surgery “to create terrifying yet intriguing aural landscapes,” per the record’s label. For its part, Plastic Anniversary’s aural landscapes are less terrifying than they are…askew.

Matmos could have chosen to use the sounds of plastic to make a very different sort of record, perhaps one more directly reflective and/or critical of plastic’s impact on our world—like a mournful one, akin to William Basinski’s The Disintegration Loops, or something negative and jagged, like an Autechre record—but they didn’t.

Instead, they made a Matmos record, which is to say that Plastic Anniversary is filled with the same bizzaro, pop-eyed lunacy and surprise as the rest of Matmos’s albums. For years, Matmos has consistently made playful music that unsettles in its playfulness. Even what is probably the most straightforward “club” song in their catalog—”Spondee,” from A Chance to Cut Is a Chance to Cure—is a house banger (at least for its first half) with disconcerting, non sequitur hearing test lyrics. Sunshine. Lunch box. Playground. Raincoat.

***

One of the earliest recorded pieces of musique concrete (which Matmos’s own Drew Daniel defines as “music that uses sound as raw material to be manipulated and reshaped” in a Pitchfork piece) is “Etude aux chemins de fer,” which translates roughly as “study of the railways,” by genre pioneer Pierre Schaeffer. The song was the first in a cycle by Schaefer—Cinq études de bruits—broadcast on French radio in 1948, and is an instructive example of musique concrete.

The track opens recognizably enough, with whistles and the familiar chug-chug-chug of a train. But before long the knocking railway tie sound establishes a kind of “beat” motif that comes and goes, interspersed with otherwise familiar rail-related sounds that, by being stripped of their usual context and repeated and distorted, establish the structures of a song. “Etude aux chemins de fer” is both recognizable in its source and disconcerting in its use thereof. I can only imagine how it sounded to its initial audience, who had just lived through the upheaval of the Second World War.

Matmos’s musique concrete is a faithful, if much, much, more complex descendent of Schaefer’s. Though it’s fun to try, one can rarely—even when one is given a clue by a track’s title, such as Plastic Anniversary’s “Interior with Billiard Balls & Synthetic Fat”—so easily divine Matmos’s song’s sources and how they’re being used. This is part of what protects Matmos from being labeled a gimmick act: that the manipulation of their sources is so deft that their sources could be almost anything. Were “Etude aux chemins de fer” a dessert, for example, it might be a nice fruit galette; Matmos’s music is closer to a towering croquembouche.

***

In an interview with French TV, Norman Mailer had this to say about plastic:

Plastic! (Mailer makes a mock-angry leonine roaring noise; he is handed a plastic lid by the interviewer). Children grow up sucking on this stuff. Look at it, they they, they finger it, there’s nothing, your fingertips feel nothing. If you touch a glass, you feel a little bit. If you touch wood, you feel quite a bit. But when you touch this, nothing comes back. And you’ve had now, for four decades, more and more and more infants and children live with this stuff and play with it, and you cannot possibly feel any affection for it.

After all, what is plastic when you stop to think about it? Plastic is the excrement of oil, that’s how it’s started. What happened is all these people, who were making their billions, their early billions on oil, were throwing away the waste product of oil, when they refined the oil. And then suddenly somebody said, “we’re throwing away a fortune!” In the French sense, “we are pissing away a fortune!” Let us save the waste product of oil. And so now we’re surrounded by the excrement of oil.

Nobody’s ever been nourished by plastic, it’s functional. It’s the spiritual equivalent of political correctness, it’s functional. It serves a purpose, and the cost of serving this purpose is enormous.

***

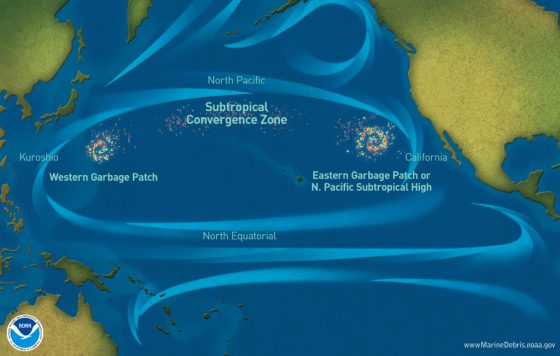

There are a number of so-called ocean garbage patches, the largest of which is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. A collection of debris in the water between Hawaii and California, according to The Ocean Cleanup the Great Pacific Garbage Patch “covers an estimated surface area of 1.6 million square kilometers, an area twice the size of Texas or three times the size of France.”

Per National Geographic, ocean garbage patches are “made up of tiny bits of plastic, called microplastics,” which can be invisible to the naked eye. “Even satellite imagery doesn’t show a giant patch of garbage. The microplastics of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch can simply make the water look like a cloudy soup.” Furthermore:

Marine debris can be very harmful to marine life in the gyre. For instance, loggerhead sea turtles often mistake plastic bags for jellies, their favorite food. Albatrosses mistake plastic resin pellets for fish eggs and feed them to chicks, which die of starvation or ruptured organs.

***

Plastic Anniversary opens on a high note, with the bouncing, squiggley “Breaking Bread,” which gives way to the more reflective, slightly epic “The Crying Pill.” This track reminds me of others in Matmos’s catalogue—like the 2003 album The Civil War’s “Zealous Order of Candied Knights,” also that album’s second track—in its off-kilter grandeur and use of steadily increasing volume. “The Crying Pill” is also the track on Plastic Anniversary with the most “normal” sounds and instrumentation, despite being derived from “the excrement of oil,” per Mailer.

What follows is are the knocking billiard balls and navel-gazing of “Interior with Billiard Balls & Synthetic Fat,” the eleven-second interlude “Extending the Plastisphere to GJ237b” (which is reminiscent of the Optiganally Yours cover of Herb Alpert’s “Spanish Flea,”), and then the album’s single, “Silicone Gel Implant,” which over the course of its four minutes goes from a bouncy, somewhat whimsical track to something more dissonant.

Indeed, this turn toward “darker” sounds midway through “Silicone Gel Imprint” signals a shift across the album. The second half of Plastic Anniversary, like many Matmos albums, is less overtly fun—if more intellectually interesting; once upon a time, on Twitter in Twitterspeak, I referred to their work as a “mix of party & sad.” Though certainly “sad” at times, Plastic Anniversary’s second half isn’t consistently so. For example, befitting its title, “Thermoplastic Riot Shield” is as bracing as Matmos gets. Then there’s “The Singing Tube,” which is nestled between “Fanfare for Polyethylene Waste Container” and “Collapse of the Fourth Kingdom” and is a breather of a song: it isn’t as densely layered as the rest of the album, and does much with quiet. Overall, Plastic Anniversary is marked by shifts and changes, in tempo and tone. It is restless, like a six-pack ring bobbing on the waves.

***

Recently, one of my connections on LinkedIn shared a European CEO (publication title presented without comment) article on the “biophilic office.” The article’s subhead, above an image of the Amazon Spheres, reads: “More businesses are turning to biophilic design to improve their workplace environments. This approach promises both aesthetic and productivity benefits.”

Suffice it to say this article, which I saw during a period of listening and re-listening to Plastic Anniversary, and thinking about plastic and nature, bummed me out. The very word “biophilic”—which comes from E.O. Wilson’s 1984 book of the same name, and not the Björk record—bums me out too, at least when used when discussing office design, and boosting “productivity, increas[ing] staff creativity and improv[ing] workers’ mental health.” Is this what we’ve come to, to viewing the natural world as another means of boosting productivity?

The article also reminded me of John Berger’s take on the split from the natural world (via animals, specifically), from his essay “Why Look at Animals.” We have isolated ourselves with plastic.

The zoo cannot but disappoint. The public purpose of zoos is to offer visitors the opportunity of looking at animals. Yet nowhere in a zoo can a stranger encounter the look of an animal. At the most, the animal’s gaze flickers and passes on. They look sideways. They look blindly beyond. They scan mechanically. They have been immunised to encounter, because nothing can any more occupy a central place in their attention.

Therein lies the ultimate consequence of their marginalisation. That look between animal and man, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society, and with which, in any case, all men had always lived until less than a century ago, has been extinguished. Looking at each animal, the unaccompanied zoo visitor is alone. As for the crowds, they belong to a species which has at last been isolated.

***

Then there is Plastic Anniversary’s final song, “Plastisphere,” in which nature-esque, wind, animal, and rustling foliage-esque sounds abound. The song is simultaneously life-affirming and disconcerting. It sounds alarmingly like rain and wind in trees, with bugs and birds in the distance; there is a steady crackling hum akin to rain that comes and goes throughout the song’s length. That these sounds were derived from plastic (plastic!) is perhaps Plastic Anniversary’s greatest testament to Matmos’s technical skill.

Then there is Plastic Anniversary’s final song, “Plastisphere,” in which nature-esque, wind, animal, and rustling foliage-esque sounds abound. The song is simultaneously life-affirming and disconcerting. It sounds alarmingly like rain and wind in trees, with bugs and birds in the distance; there is a steady crackling hum akin to rain that comes and goes throughout the song’s length. That these sounds were derived from plastic (plastic!) is perhaps Plastic Anniversary’s greatest testament to Matmos’s technical skill.

Yet “Plastisphere” is also an uncanny valley of a song (also a testament to their skill…). While listening—particularly during the song’s last minute, when the fauna sounds have disappeared and we’re left with faint wind and rustling, the sound of say a storm blowing in across a prairie landscape at dusk—you cannot avoid the uncomfortable realization that what you’re listening to is not real. That what you’re listening to is in fact trash.

But of course, that trash can be appropriated to create such (bewildering) beauty is a refutation of trash qua trash. With Plastic Anniversary, Matmos is showing us that we don’t need to let the mediocre win or, at least, a way to use it to create something far from mediocre.

…

Great Pacific Garbage Patch and beach trash images via Wikimedia. Matmos images courtesy of Thrill Jockey.