Today we visit the Archives to read this tesoro: writing lessons from Gabriel García Márquez, as remembered by Elias Miguel Muñoz in Michigan Quarterly Review, Winter, 1995.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

To Don Rob: “There is nothing more dangerous than a written memory.”

Gabriel García Márquez, The General in His Labyrinth

Five years later, as I face my Sundance memories, I am remembering that distant day when Márquez walked into the room. It was the ninth hour of an August morning; early, we thought, for no one expected the renowned Latin American writer to arrive on time. What preceded this man was a daunting body of literature, a trajectory befitting a Nobel laureate. We were fortunate: Gabriel García Márquez was going to be sharing ten days of storytelling with us. We would be working with him in a log cabin hidden in the Utah forest. The place was pastoral and homey: simple rustic furniture, a round table, a window that revealed dense foliage and winding trails.

We were talking, trying to relax, to soften our frozen, self-conscious smiles. The program director had coached us the night before: Don’t let anyone, outside your family, know that he’s here. Not a word to the media. But this preparation hadn’t made any sense. None of it had registered because there was a chance the workshop might not happen. Because Márquez might never show up.

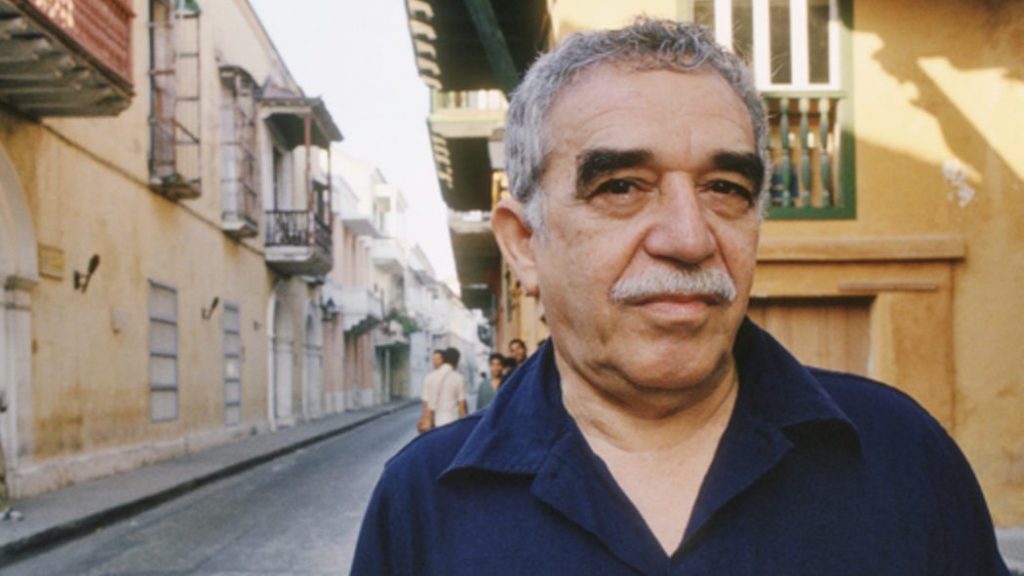

All conversations came to a halt when we saw him. The legend was finally incarnate: ample eyebrows of tangled grey hair, a timid smile, blue denim overalls, his walk of languid steps. Before getting started, he makes a special request: he’d like for us to call him Gabo. He has reviewed our files, he says, but wants us to refresh his memory. We begin to introduce ourselves, clumsily holding cups of light coffee, or clenching manuscripts (treatments for a half-hour film: our assignment). When my turn comes, I tell him what he already knows: I was born in Cuba, left twenty-some years ago. I’ve written two novels about my exile experience. He laughs and says: “Qué bien. That is all very well. But beware! I’ve also written some novels and see the mess they’ve gotten me into!”

Gabo tells us he’s read an interesting article in the Salt Lake City paper this morning. It is the story of a naked man who goes into a Hollywood restaurant and is refused service. The man feels insulted. “Why won’t you let me in?” he asks. “Because,” the host responds, “you’re not wearing a tie.” Gabo wants to know our opinion: “What do you think? Could we make a movie out of this?”

The Utah article wouldn’t result in an actual film. But the Sundance group would manage to create a hilarious story based on the nude Hollywood man. We would spend five hours a day weaving imaginative plots, discussing movies, and mostly just listening to the great storyteller.

*DISSOLVING ICE*

In the summer of 1989, Gabriel García Marquez directed a writing workshop at the Sundance Film Institute in Provo, Utah. There were eight participants: Chicana fiction writer Helena Viramontes, Nuyorican playwright José Rivera, Chicano film student Enrique Berumen, Cuban American filmmaker Ela Troyano, Japanese-Brazilian director Tizuka Yamasaki, Spanish filmmaker Mariano Barroso, Chilean poet Fernando Palacios, and myself. We had been chosen from reportedly thousands of candidates to participate in this workshop called “Narrating for Film and Developing the Imagination.” The event was sponsored by the Institute’s Latin American Program, which at the time was under the direction of Colombian filmmaker Piedad Palacios. Robert Redford had made all the arrangements. The actor and founder of Sundance had met Garcia Marquez while lecturing at the Escuela de Cine in Cuba. Márquez had agreed to come to Provo as a token of his friendship with Redford. And it was thanks, in part, to the movie star’s leverage that the U.S. government allowed the novelist to enter this country. “El Bob,” as Gabo liked to call Redford, had managed to get Fidel Castro’s most famous friend a visa.

Five years later, today, I have surrounded myself with photos and journal entries from that workshop. I am now searching through my notes in order to produce a brief memoir. This time I am determined to write it; there have been too many false starts. The opening line of One Hundred Years of Solitude immediately proves useful: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.”

This wondrous entry into the world of Macondo will break the ice – my ice, which has dissolved every time I’ve tried to put memories into words. Because on each of those occasions, the same questions have held me back: How do I tell the Sundance chapter of my life without betraying Gabo’s confidence? Can I talk about Gabriel García Márquez without disclosing his ideas? Worse yet: without appropriating them? The answers to those questions will be there implicitly, as I compose my portrait of the novelist. Gabo can rest assured that I won’t make him say things he never said, or discuss those stories that he has yet to write. I have only one objective, and that is to show my debt to Márquez. His ideas were fruitful: they have been fertile soil for my growth as an artist. Sundance was my rite of passage into the writer’s labyrinth, into the realm of the imagination. Ultimately, this is not really a memoir about a Nobel laureate, but the tale of a man who loves telling stories.

*THE STORYTELLER’S METHOD*

Before being a disciple of Márquez, I had been a professor of his magical realism. Not only had I read Gabo’s books, I had dissected them. I had coaxed from my students clever “analyses” of his labyrinths and butterflies and levitating priests and flying carpets. The yellow color of bananas and flowers had to have a function. Was it a leitmotif? And what about the archetypes from which emerged Márquez’s colonels, his bellicose patriarchs and his industrious Ursulas? Life and death are both dimensions of existence in the Marquezian universe, I lectured. His texts are carefully constructed on the moving sands of a time that is fleeting yet circular. The symbolism of the names is important, I thought. Arcadio signified Arcadia, paradise lost; Eden, the newly founded territory of Macondo, colonial Latin America. Utopia?

Gabo would later inform us that he gleaned the names of his characters from discarded phone books and dilapidated tombstones, without consciously thinking about the names’ symbology. The Colombian novelist would bring me down to earth, back to the meat of his texts, to the substance of fiction, which is storytelling. After attending Gabo’s workshop, I’d never again be able to have my students seek the hidden meanings in the Márquez novels. There would always be a critic in me. Yet I could no longer approach One Hundred Years of Solitude as a text to be deciphered, but as a journey to be enjoyed and cherished.

Márquez presented himself from the very beginning as a humble cuentacuentos with a handful of advice. He said he had a “method” and he was willing to share it with us, although he couldn’t recommend it. “And that’s because,” he explained, laughing, “to appreciate my method you have to have lived for sixty years. And you need to have eaten a lot of Jell-O and drunk many mouthfuls of ‘Emulsión de Scott’ when you were a kid!”

There was no secret formula to being a writer. Gabo could only provide some useful tips. “Stop writing when you get tired,” he advised. Between 9:00 in the morning to 3:00 in the afternoon he locked himself up and did nothing but write. Once the typewriter was turned off, he didn’t think about the story until the next day. “I put it out of my mind,” he said. “But I always make sure to stop working where I’d like to begin again.” Gabo warned us not to approach the page in a bad mood. “Nothing affects writing more than bad blood, rancor, envy,” he declared. “My mood always shows in what I write.”

All these recommendations are fine, I thought. But there were “serious” questions in my secret agenda that kept gnawing at me: Is there a creative impulse? Does Gabriel García Márquez believe in inspiration? “The force of inspiration does exist,” Gabo affirmed. He intimated that there are certain experiences that cannot be explained or defined with our rational minds. In the act of writing, he believed, a “supernatural force” takes over, something like a “state of grace”….

Read the rest of Elías Miguel Muñoz’s recuerdos de Gabo in our Archives.