For much of the world, Ireland has become a commodity, a tourist attraction, reduced to its market value, castrated of its cultural nuance.

It is this exact reduction of national identity that The Wake Forest Series of Irish Poetry seeks to combat. Volume Four, compiled by David Wheatley, spotlights five contemporary Irish poets: Trevor Joyce, Aidan Mathews, Peter McDonald, Ailbhe Darcy, and Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh. Before each section of the anthology is a critical essay that situates each poet’s work in a national, global, and historical conversation about Irish poetry. Their perspectives and motives as poets are various: Trevor Joyce is writing within an experimental tradition, Aidan Mathews a religious one; Peter McDonald’s work addresses the Northern Irish tensions of identity as British, as Irish, as neither, as both; Ailbhe Darcy writes from her position as an Irish person who has since left, and built a career, outside of Ireland; and Aibhe Ní Ghearbhuigh, an Irish-language poet, asserts in her work the urgency and the importance of writing in a language that is often regarded as moribund — to say that the language, and the people who speak it, still have, and have always had, cultural clout.

Editor David Wheatley, in his preface to the book, writes that his aim in assembling the series is to “sidestep questions of generational groups and territoriality to explore a series of related but distinct issues, as focused on these five poets’ distinguished bodies of work” for an American audience. But it is nearly impossible for American readers who have even a basic knowledge of Irish history to examine Irish literature without such questions looming; they are undeniable producers of life in the discursive ecosystem in which Irish writers exist. Take, for instance Aidan Mathews’s poem “Courtship,” which narrates the nascent stages of the relationship between a speaker and his spouse: “Ours was an old-style Irish romance, / A slow advance from head to haunch.” It’s a pithy description of the chastity that is so readily ascribed to Irish intimacy, which is, of course, a product of the nation’s inherited Catholicism.

Editor David Wheatley, in his preface to the book, writes that his aim in assembling the series is to “sidestep questions of generational groups and territoriality to explore a series of related but distinct issues, as focused on these five poets’ distinguished bodies of work” for an American audience. But it is nearly impossible for American readers who have even a basic knowledge of Irish history to examine Irish literature without such questions looming; they are undeniable producers of life in the discursive ecosystem in which Irish writers exist. Take, for instance Aidan Mathews’s poem “Courtship,” which narrates the nascent stages of the relationship between a speaker and his spouse: “Ours was an old-style Irish romance, / A slow advance from head to haunch.” It’s a pithy description of the chastity that is so readily ascribed to Irish intimacy, which is, of course, a product of the nation’s inherited Catholicism.

Still, if the discourse surrounding Ireland is an ecosystem, this anthology diversifies it, or, more accurately, illuminates its existing diversity, beyond the Irish writers that American readers would be likely to already know (W. B. Yeats, James Joyce, Samuel Beckett, Seamus Heaney, Eavan Boland, Matthew Sweeney, Medbh McGuckian, and so on). The previously mentioned lines by Mathews, for example, resist common misconceptions of Irishness, which is generally that the Irish are a battered, self-serious people: the lines are emotionally complex, sticky with good-humored self-effacement; they engage with Irish customs and perceptions of Irish people in one breath, and poke fun at them in the next.

Similar subversions of readerly expectations of Irishness thread the book. For example, the title of Peter McDonald’s poem “The South” implies that the poem will be a meditation on the Republic of Ireland as it relates to Northern Ireland, McDonald’s nation of origin. Instead, though, the poem makes its readers traverse the map, and moves them “much further south” — through the Falkland Islands, past Chile, until ultimately we are in Antarctica:

stuck at a weather station,

listening for the news from the Malvinas,

a thousand miles from here to anywhere.

Ailbhe Darcy more explicitly disrupts readerly expectations of Irish identity in her work. One of her poems, titled, “He Tells Me I Have a Strange Relationship” (“with my city,” the first line continues), examines the problem and the inherent violence of conflating the self so closely with country. The beginning of the poem works within an old Irish tradition of converging the body with the nation:

…here’s the vein on my left wrist

fat as Liffey, my right skinny

lost Dodder; slit,

they run murky and thick

with city.

But the poem ends with a criticism of that tradition, gesturing at a feeling of entrapment that the speaker feels in the face of it. “I cannot leave,” she says, even though she has physically left Ireland:

It is a narrow, self-effacing swathe,

the shape of me—

enough scar to fret at, too close to desire or despise.

If Dublin is kicks in the shins, my shin

is its sweet spot, summer lunchtime Stephen’s Green.

The anthology opens with the words of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writer Stopford Brooke: “It is only quite lately that modern Irish poetry can claim to be fine art.” If Irish poetry could not claim to be fine art before the twentieth century, it is not because there was a lack of Irish poets with talent and voice; rather, it is because the literary world ignored them, or willfully caricaturized them. Though the problem persists, this anthology makes it clear: the work of Irish poets is undeniably diverse, crafted with rigor, and historically urgent. They have more than earned a place within literary canon — and they are here to stay.

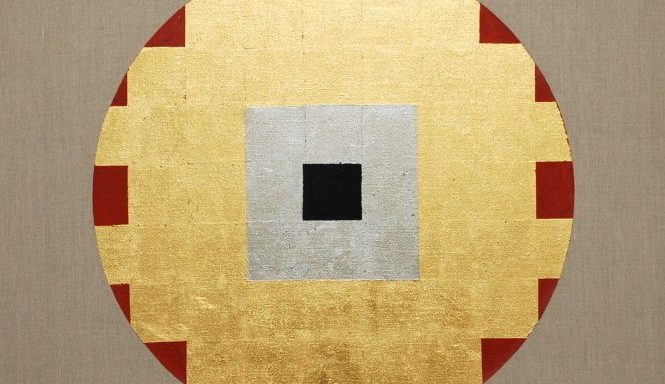

Image: Mixed-media artwork by Patrick Scott.

Clare Hogan is a writer from Chevy Chase, Maryland. Her poems have received a Meader Family Award and an Academy of American Poets Prize. She received her MFA in poetry from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program at the University of Michigan, where she is currently a Zell Fellow in poetry. Follow her on Twitter @squarehogan.