This review of Caroline Johnson’s The Caregiver is published in conjunction with MQR’s forthcoming issue dedicated to Caregiving & Caregivers guest edited by Heather McHugh.

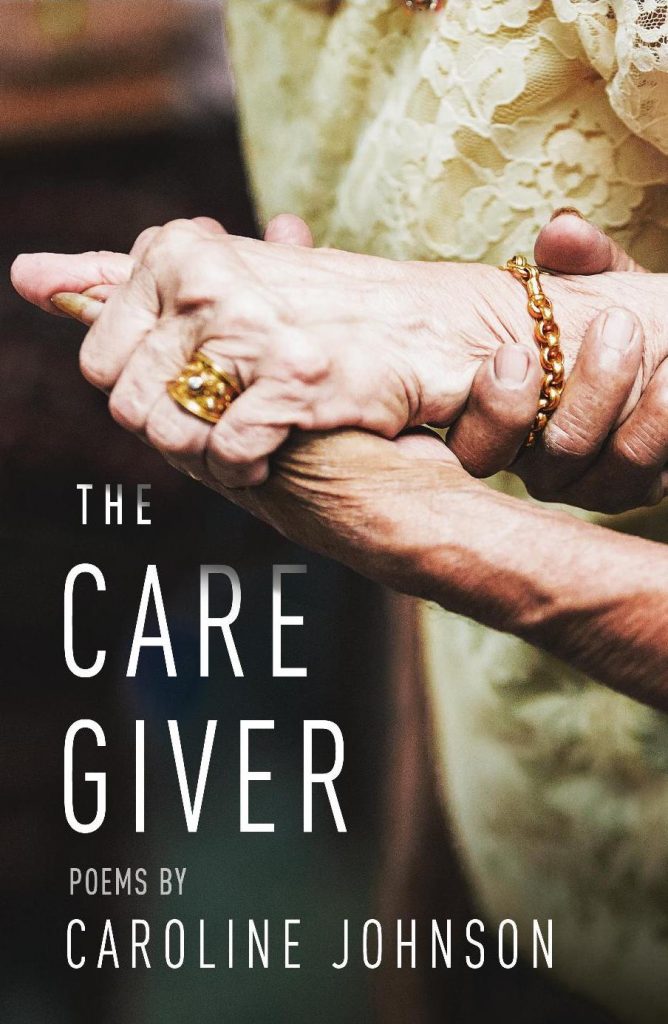

Adults that must arrange care for their parents or loved ones face a confusing, emotionally challenging task. Poems can capture the rollercoaster of feelings and offer close-ups of the experience, and Caroline Johnson’s The Caregiver (Holy Cow! Press, 2018) does both, offering honest and moving accounts of her own journey as caregiver to her aging parents.

Johnson, a college advisor as well as a poet, was a caregiver for twelve years for her mother, who had Alzheimer’s Disease, and her father, who had Parkinson’s that was later diagnosed as the rare degenerative disease Multiple Systems Atrophy. In the book’s prologue, Johnson comments on the circumstances that informed many of the poems in the narrative, autobiographical book: watching films with her parents; learning about her father’s work as a bomber pilot in the Air Force during Cold War; and working with her parents’ principal and patient caregiver, Donna.

Johnson, a college advisor as well as a poet, was a caregiver for twelve years for her mother, who had Alzheimer’s Disease, and her father, who had Parkinson’s that was later diagnosed as the rare degenerative disease Multiple Systems Atrophy. In the book’s prologue, Johnson comments on the circumstances that informed many of the poems in the narrative, autobiographical book: watching films with her parents; learning about her father’s work as a bomber pilot in the Air Force during Cold War; and working with her parents’ principal and patient caregiver, Donna.

The book opens with the poem “Sunsets,” showing us the three of them together in the years of her mother’s Alzheimer’s Disease, watching Titanic: “Leonardo DiCaprio’s lips are turning blue. My mother’s / arms are scaly and dry. I put lotion on her arms. / I put lotion that smells like coffee on my father’s legs, / bright with red sores. I tuck them into bed / and spread the fat green comforter over them.”

The rest of the book is divided into three numbered sections — a first section of poems about her father, a second about her mother, and a third of her own grief over the loss of each parent, including the last, very long, stunning poem “Der Schrei” (“The Scream”), a piece that follows Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and begins:

I saw the best minds of my parents’ generation destroyed by long, lingering disease, bodies torn by knee replacements, gout, crippling neurological ailments, rheumatoid arthritis,who fought valiantly against urinary tract infections and shingles

who left home so many times because they forgot where they were and who they were

who lay in soiled diapers patiently waiting for someone to change them

who never complained about boiled broccoli or mashed potatoes

whose suppositories worked only sometimes

who woke in the night crawling, kicking, screaming, only to be pacified by Xanax and cranberry juice

who gave up their car, their cane, their wheelchair, and then their kitchen to move to a hospital bed

whose pressure-sensitive mattress didn’t prevent bed sores

whose pressure-sensitive mattress didn’t prevent bed sores

who smiled despite dementia and dentures

who still celebrated Christmas and Thanksgiving and Easter and birthdays with cake and candles and presents like Frango mints and Old Spice

who fell down so many times we lost count, making dents in the plaster walls that we spackled and painted, and dents in the car from driving

who could recite the Gettysburg Address, look you dead in the eye and say they are proud of you, then ask who planted bombs in their bed

who cried and shrieked about what they saw in the yellow wallpaper, then turned over and went to sleep for good

who got angry and made fists and accusations, full of grief and depression and fear and terminal anxiety

who sometimes thought of lonely gravestones with roses and crosses but as atheists turned their backs again and again against God

who learned to breathe all over again with oxygen machines before learning to let go of life

who once flew a B-47 and made a hole-in-one and whose demented wife was always leaving for Alaska very, very soon.

In the book’s title poem, “The Caregiver,” Johnson reflects on her parents’ principle helper, Donna, who shows the poet what it means to care for another “beyond all thoughts of myself”:

See this Lithuanian woman. She has been

feeding my father dinners of mashed turkey

and broccoli, potato pancakes, washing his

clothes, bathing him, offering him the choice

between Wolf Blitzer and Vanna White for years.

Observe her hands as they gently push his body

to the side of the hospital bed. They are covered

with latex gloves. Consider the way she has taught

me to tenderly pull up his socks and cover him

with a quilt, put drops in his eyes, rub powder

on a rash, splash his neck with Old Spice, then

bend down to kiss his cheek goodnight

You must come closer, you must hang up your jacket,

be prepared to spend hours listening to his slurred

speech, help feed him applesauce with vitamins,

raise and lower his bed, monitor his erratic heartbeat.

Remember what he has given up—his Buick LeSabre,

his cane, his walker, then finally his wheelchair—to get

to where he now lives, a bed with guard rails.

Go to the night-stand and offer him a Frango Mint.

Put on his favorite Garrison Keillor CD. Listen as he

Smiles with his one good eye and whispers something

so faint, you ask him to repeat, “I’m lucky.”

Think about all this while driving the long way home.

You may get angry at the world, like I do, until you

see your husband asleep in the Lazy-Boy, bare legs

dangling. Until you suddenly realize what the caregiver

has taught you as, without a word, you slowly rub lotion

onto your husband’s chapped heels, then cover his ice-cold feet.

Animals that she’s encountered also enter the poems — turtles remind her of her father; a coyote crossing freeway traffic, of her mother. In “Coyote,” she writes, “You are like that coyote now — strong, free / and healthy — conquering all fears and / blissful of your surroundings. You have / crossed the road of troubles, and emerged to return into the forest of your life.”

In “Hospice,” a poem dedicated to her father, Johnson writes:

When you watch someone die

you must sit up close and open

your heart to pronounce each vowel,

you must let your loved one

embrace the air, let his arm

extend towards infinity,

you must help him

touch the stars.

When you watch your father die

remember it is a privilege

to stroke his stone cheek

to kiss his forehead,

to tuck his air behind his ears.

You must try not to be

so important, you must wave

when he decides to leave.

When you watch a bomber pilot die

who once got lost in the threshold

of a dream, remember he no longer

needs his walker, his cane, his wheelchair,

remember there will come a day

when he will no longer need you

will no longer need his body

though you will pray for him

to bring back the light as he flies

past one thousand sunrises in the sky.

These are skilled poems of Johnson’s own journey, and they speak movingly to the similar journeys of millions of caregivers.

Robin Chapman is Professor Emerita of Communication Science and Disorders at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a poet, and a painter. She teaches poetry workshops at Bjorklunden and The Clearing in Door County, Wisconsin. She is author of nine full-length poetry collections, including most recently Six True Things (Tebot Bach, 2016) and The Only Home We Know (Tebot Bach, forthcoming).