“On Return & Redemption: Ed Madden in Conversation with Kwame Dawes,” is published in conjunction with MQR’s forthcoming issue dedicated to Caregiving & Caregivers guest edited by Heather McHugh.

I have known Ed Madden for over two decades, and I have long admired him as a remarkable teacher of prosody as well as a superb writing workshop leader. His workshops are frenetic, dynamic, and impeccably well-organized sessions that leave the participants with a sense of elation and achievement. Madden is a poet — a man who has fully committed to the life of engaging the world through the celebration of language and the pleasures of constantly seeing some meaning and value in the world around us, even when the world is filled with cruelties and the inexplicable.

It is worth saying that I know few poets who write about flowers and gardening with the level of complexity and pure joy as Madden. One would have to compare him to someone like Jamaica Kincaid, whose gardening essays come the closest to the poetic feeling in Madden’s poems. I have, all these years, read his poems at all stages of their development, from enviable first drafts to fully fleshed-out and realized.

Madden has published four collections of poetry, and he has lived his life as a poet in the community, having taught hundreds of workshops in South Carolina and around the world in addition to serving as Poet Laureate of Columbia, South Carolina, where he lives and teaches. His poetry has given us a necessary narrative of a man working through the complexities of faith, identity, and sexuality — yet it is hard not to recognize in his entire oeuvre the fundamental expression of how to love in this world. Madden is a gay man, and that is a hard fought statement. His poetry teaches how this art of ours, when driven by an unflinching quest for truth and sincerity, can constitute deep pain and beauty.

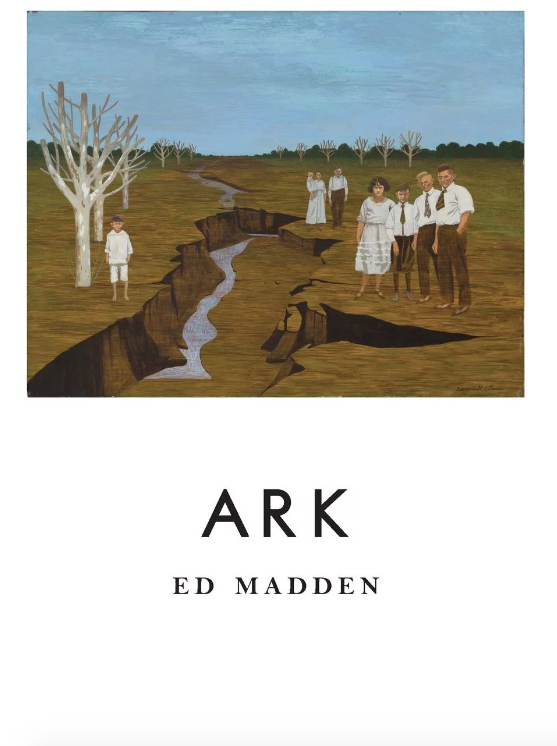

It is impossible to miss in Madden’s work, in the mere fact of his poems, a profound optimism. When his father was dying in 2011, he took time off to return, a kind of prodigal, to his home in Arkansas to, in many ways, find out if that farm was truly home for him and to work through the difficulty of caring for a father who had long expressed disappointment about Madden’s gayness. Ark (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2016) is the result of this deeply unsettling, but necessary journey. Our conversation, conducted via email, focuses on what I regard as one of Madden’s most compelling collections of poems. What is revealed here is a poet of great sensitivity and skill, but also a man who sees himself as having a great deal more to explore as a poet.

Additional poems about this period in Madden’s life — work forming the basis of this interview — will appear in the Fall 2018 issue of MQR, a themed issue focused on caregiving.

—Kwame Dawes

KD: Ark is consistent with all your other work that quite explicitly engages the language and iconography of Judeo Christianity in general and, it would seem to me, evangelical Christianity in complex ways that can’t be explained by approaches like irony, parody, or counter- or alternate narratives. The Bible figures significantly in this work, as well. But your own experience of issues of faith and identity have certainly shaped much of your poetry. Can you talk a little bit about your “faith” background, and how it informs your poetry?

EM: I grew up in the Church of Christ, which grew out of a restoration movement in the nineteenth century in the U.S. If people know it, they usually know there are no musical instruments in the church. It’s an odd characteristic, but it suggests the deep reliance on scripture that drives the tradition. There are no musical instruments in the New Testament, we would say, so there’s no scriptural precedent for using them in worship. We ground our faith in scripture alone. It’s not just a way of deciding how to worship. And it’s not easily reduced to that label fundamentalist. It is a worldview — the idea that anything we know or need to know can be found in the scripture. I grew up thinking we were the one true church, and everyone else was in error. Maybe that makes me a little suspicious, or little cynical, about anyone’s claims to spiritual truth now, but still the language of the church stays with me.

Because scripture was so important, I grew up steeped in the language and stories of the Bible. The King James version, of course. Scripture wasn’t just some elevated language you used for prayer and worship. It was a set of principles you built your life on, it was a collection of stories you knew, and it was a repository of phrases you could use — it would slide in and out of daily discourse. And it was the language of who we were. I think that’s the first thing I’d say about how my faith tradition influences my writing: that I am steeped in the language and stories of scripture, and they are part of who I am.

Because scripture was so important, I grew up steeped in the language and stories of the Bible. The King James version, of course. Scripture wasn’t just some elevated language you used for prayer and worship. It was a set of principles you built your life on, it was a collection of stories you knew, and it was a repository of phrases you could use — it would slide in and out of daily discourse. And it was the language of who we were. I think that’s the first thing I’d say about how my faith tradition influences my writing: that I am steeped in the language and stories of scripture, and they are part of who I am.

I should say, too, that when I was a kid in rural Arkansas, church was inextricable from family and community. I grew up on a farm that my dad farmed with his own father and brothers. His sisters married farmers who lived nearby. I grew up within a few miles of both sets of grandparents. We all were part of the same faith tradition, and most of us went to the same rural church. So family and church blurred into how I understood community. Maybe that sounds like a good thing, but it has its risks, too. We practiced adult baptism, so coming of age in the church meant a real pressure to be baptized, a compulsion almost. It was the marker of belonging. We were a culture of conversion stories. I remember those summer gospel meetings — the fear of hell and being lost, the urgency about being saved. Even after baptism, we were constantly called to go before the group and confess our sinfulness and recommit our lives to Christ.

So what I value about community comes from the church of where and when I grew up, but the church also taught me about who fits and who doesn’t, who is one of us and who is not. I think the family farm and those memories of community continue to haunt my writing as a possibility of what could be. But I know there are risks. There are ways to belong, and there are ways you no longer or can never belong. Being gay taught me that.

While I was attending a church-based college and later in graduate school, I was slowly, at first unwillingly, later desperately, coming to terms with being gay, and with the fact that my sexual identity and my faith community were incompatible. To be gay is to be outside the community, an outsider, outcast, cast out. Even though my faith was important to me, being gay made that seem impossible. I think I was always trying to be really, really good, because I knew how bad I really was. After I came out to my family, my dad said in a letter that he would rather I’d admitted I murdered someone — he could deal with that, he said. I swallowed all that condemnation and shame and made it part of who I was. It is really hard now, looking back, to remember how terrified I was of my own sexuality, and of how my family would reject me. I think the damage is deep and it remains.

So I guess I’d say it’s my language, the language of who I am and where I came from, and part of how I understand community, but as a gay man I find it’s also the language that condemns me and the community that rejects me — and in my writing I’m always grappling with that. Sometimes I try to re-inhabit or revise that language. But being back home with my dad, taking care of him when he was dying, gave me a space and time to think about all of that differently.

In a note to me, you refer to the “Ark project.” It seems to me that you regard this as a source space or experience or idea. Is this how you view this “it”? And what would “it” be beyond the passing of your father? I suppose I am asking you to define the “Ark project” and to talk about how it continues to generate work for you.

So, yes, Ark was the book of poems I wrote, based on the time I spent helping with my dad’s home hospice care when he was dying of pancreatic cancer. Some of those poems also appeared in the earlier chapbook, My Father’s House (Seven Kitchens, 2013). To some extent, I’m still working through that time and place, so I continue to write poems, like the ones in this issue of MQR, about that time and that place and what it means to me, then and now. My father and mother had cut me off — my dad literally did not communicate with me for almost a decade — and then there I was, in my childhood home, helping to care for him. I had given up on them. I think when they cut me off, I also cut them off. I tried to mourn the loss of living parents and move on.

So for me it’s not just about the specifics of my father dying or my being there with them. It’s about paying attention to those we love, despite the hurt or the anger. It’s about who I am and who they are, and who I was and who I may still be. It’s about paying attention to my own history and my own heart and what they can tell me. It’s about how I can define myself within and against a culture and a history and a language and a past that is at odds with who I am — and yet maybe not as much at odds as I would like to think.

I don’t know. It’s a time and place to just say, I don’t know, and pay attention to what happens after that.

I have thought a lot about the ways in which the symbolism of Ark offers you a range of curious possibilities here. The least overt is the pun on “arc,” which may have much to do with the idea of a narrative arc that seems to be foregrounded by the encounter with your past, your childhood, the intergenerational dynamic of your life wherein these last months with your father, and the attendant complications with the rest of your family, constitute pivotal moments in this personal narrative.

So, there is that. More obvious are the two core references to the ark. The first being the ark of Noah, and one does see elements of the patriarchal notions of beginnings, a latter day Edenic inversion with the archetypal Noah and his wife. And this is the ark of disaster, of God’s judgement, the tensions of it all, and the hope of the receding flood. Images of birds, of water, of flooding, and much else, are not hard to spot in the work. The last, of course, is the Ark of the Covenant — and here themes of faith, commitment, loss of faith, even betrayal, strike me as opportunities for tension, poetic revision of notions of identity. This is rich stuff and the poems, even if not always explicitly, are certainly engaged with this idea of who belongs and who does not belong, who is in and who is out, what is judgment and what is not judgment. I do mean to lay out how I am floundering for implication and meaning, and I am curious about how you want us to read these poems — to read this book.

Yes, yes, yes, I love all of what you are saying! For me the starting place was Noah’s ark. We were a little family in a little house surrounded by water. That spring when I was home with them, there were floods all around us. The fields around us were flooded and water came only yards from the house, and the road out was repeatedly covered with water. And then there were all the animals that kept popping up at the house and into my writing.

Noah’s ark was also my favorite toy when I was a kid, one of those stories I grew up with. The fact that the story is all about survival in the face of disaster and judgment, and maybe the fact that the story ends with the condemnation of one of Noah’s sons, these things made it work for me as a kind of centering device. In a lot of my work, it’s the father-son stories from the Bible that obsess me — Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, the prodigal son, David and Absalom. There’s that element in the story of Noah, too, but it’s like an afterthought, the story is really about the natural world, it’s about what must be done in the face of disaster, and it’s about covenants, promises.

My publisher, Bryan Borland at Sibling Rivalry Press, is based in Arkansas, and he suggested that the book is also an Arkansas story. (Ark. used to be the postal abbreviation for Arkansas.) I do like that, and we used Carroll Cloar, an artist born in Arkansas, for the cover image. And the landscapes and maybe some of the cultural markers are indicatively Southern. But I hope some of the broader themes of the book — family alienation, maybe especially over religious issues, and family reconciliation, and the experiences of terminal illness and of caregiving — I think these themes can speak across cultures. Our parents die. Our loved ones die. This changes us. This breaks us.

In the poem “Grief” with its wonderful metaphor of stitching — or perhaps taxidermy — there is the alluring statement: “Grief is a private religion // of color and touch…” In many ways Ark is a book-length elegy. What have you learned about grief in the making of these poems?

That it’s messy. That no book can prepare you. That it is physical. And that the death of a parent sets you adrift, knocks your world off its orbit and yet you wobble on. I am thinking about Sharon Olds’s poem “The Glass,” from The Father, where the death of her father is like the Copernican revolution — she doesn’t say it so baldly, of course — but it knocks the center out of your universe.

For me, the grief I associate with my father’s death is multiple. There was the grief I felt when he cut me off, and the mourning — unacknowledged, and I would not have called it mourning then — the mourning I endured for years, knowing he was still alive but severed from that relationship. And when I went home to help care for him, what I experienced as his dying was so awful, also experienced as a renewed relationship. I don’t think my brother or mother recognize that — that what they experienced as a long loss was for me, for that moment, a small gain, a second chance with that which I thought was already lost to me.

And then a door seemed to open in my relationship with my mother, too, after my father’s death, and then after the book was published, it closed again. I don’t know if it’s because she doesn’t want me writing about family material, or because she doesn’t want to remember that time, but it’s clear she doesn’t like the book. She doesn’t like that I have written about them. My sexuality remains a barrier because of her religious beliefs, and I suspect also the shame she feels in her community for having a gay son, a shame that maybe I unconsciously hoped could be mitigated by my caregiving. It’s difficult to say this, but I do think that, aside from the sense of duty and love I felt for them, I probably also wanted to earn their approval. We haven’t spoken in over a year now, and I’m grieving all over again the loss of a relationship I thought might have been — at least partially — renewed.

I remain deeply moved by those poems. These have been difficult poems that seem to function within a theology of redemption—but it is a uniquely personal sense of redemption. How does Ark constitute a path towards redemption? Is this important to you, to your work?

It is, though not in the traditional theological terms I grew up with. I don’t believe that anymore. I can’t.

I think part of what made that time with my dad so transformative for me is that we all reached a place where taking care of my dad was more important than my being gay and what they thought of that, and how we had been divided from one another for so long, and why. After the one time my dad brought up homosexuality at the hospital — asking if I had read Romans 1 lately — neither he nor my mom brought it up while I was at home. Of course, they also didn’t talk about my partner, and I was mostly complicit in the silence, but we needed that fragile truce to be able to do the work that had to be done.

And so I think about the stakes of that, for them and for me. And I wonder will I ever be able to be in that space wholly as I am. Or will I ever be able to take my partner, Bert, to meet my mother or my brother, whom they have refused to meet. I am welcome there, I’ve been told, and he is not. What will it take to make that possible? We have been together almost twenty-three years. After two decades of shaming and shunning, you’d think we would all start to realize that that is not going to work.

What will it take? And if it never happens — and if it is never going to happen — how do I live with that without letting it warp me? The return was a kind of redemption. How do I hold onto that time and place? Where else can I find what was promised, or possible, in that place? Or let that possibility be enough? Can I just let that period I spent in caregiving — in discovering a kind of tenderness I didn’t know I had in me — be an end and not a means? Caregiving isn’t just doing things for someone, it is an attitude toward the doing and toward the person and the person’s body. It’s a turning toward the other.

I am not sure I answered your question. This is a difficult question.

I am not sure I answered your question. This is a difficult question.

“My father is a puzzle box” you say in “After Long Silence.” Ark also begins with an almost dreamlike moment of domesticity that is rich with mythology, but always the poems seem to be trying to make sense of a father (and a mother) without confidence. Is Ark an attempt to “un-puzzle” this puzzle?

Yeah, but I don’t think I ever do. When I got home and moved into my childhood bedroom, which had been converted into a guest room, my old Hardy Boys books and nature guides were still on the bookshelves, but the bathroom closet was full of vases, most of them from when my mother had been in the hospital after a car accident. They were empty vessels from a time I had had little contact with them. Reminders. So I have these things that are absences, that let me know I don’t know things, and I can’t. All I can know is this moment, this brief time with them. My dad remains a mystery to me. My mom remains a mystery to me.

I have always admired your deeply intense fascination with and awareness of landscape. But very specifically, you write about flowers, about gardening in the domestic sphere better than pretty much any poet I know. I am sure you are aware of this, but how important is it for you to ritualize the art of gardening in your poetry?

Thank you, Kwame. To some extent it’s just writing about what I know and what I do. I grew up on a farm. My dad and brother would both probably say I wasn’t a very good farmhand, and I wasn’t, but that background does make you, I think, attentive to landscape and weather and the botanical world around you.

I’m also fascinated with the language of flowers, not the Latin names but the common ones, and all the inaccuracies and metaphors you find there. In my yard, there is a tiny blue wildflower with small oval leaves flat against the ground. It’s called elephant’s foot. We once bought a native spiderwort at a roadside garden stand, and the saleslady called it frog eyes. I love those names. I think for me there’s something about the naming of things that is magical, a kind of making, like poetry. And there’s something pleasurable about a litany of plant names, like a ritual, a prayer. It’s a way of — I almost want to say it’s a way of controlling or fixing — but maybe more just a way of placing things in the world. It’s a kind of specificity. Like the names of all the colors on the paint tabs at the hardware store. Or, as Foucault would suggest, all those taxonomies of perversion. Naming is magic.

Gardening for me is ritual. It is a kind of care. Not just for the world around you, for the plants you tend, but for the relationships it enables. Gardening is something my partner and I have long done together. He might suggest that I like to buy the plants but he does most of the work putting them in. Still, it is something we share. There can be something erotic about that — the smell of herbs on our hands — or something religious. So I’ve written lots of poems about him and about us that are centered on the rituals of gardening.

The ritual of gardening became a different thing at my parents’ house. I would have avoided chores when I could as a kid, but while I was home, I sought out chores. I found some packets of flower seeds in the freezer, seeds my mother had saved, intending to plant them. Some of them were almost a decade old. There was something oddly symbolic in that for me — as if they had been saved for me, for that moment.

Also, years before, when the house was built, my dad had put the rocks left over from the house exterior on the bank of the ditch nearby, near the barn behind the house, intending to use them, someday, to build a walkway. And there they sat for almost thirty years. So I dug them all out and used them to build a few flowerbeds and a walkway. In a bed at the front walk, I scattered all those old seed packets my mom had saved between a few rosemary plants, just to see what might still come up.

I am always amused at the number of times you find yourself in Ireland. To say you are deeply connected to that space would be a terrific understatement. It is hard to ignore the almost agrarian sense of place that at least two major Irish poets have demonstrated in quite different ways — Patrick Kavanagh and Seamus Heaney. Are these poets important to you? I am curious about how the poets of Ireland — the literary tradition of Ireland, has shaped your own work.

I teach Irish literature and my research focuses on Irish culture, so I’ve been really lucky the past several years to be able to go over so frequently, a few times for longer research fellowships. And my third book, Nest, was published by Salmon Poetry, an Irish publisher. I do find sustenance in Irish poets, maybe sometimes more so than the American poets I have more in common with. I am a fan of Frank Stanford, an Arkansas poet, and I am trying to learn from him more about regional textures and voice, and I’m also a huge fan of Carl Phillips, who is a master at bending syntax to meaning.

But yes, because I read and teach and love Irish poetry, I’m sure that it has shaped my work, probably in ways I don’t recognize. They not only have the agrarian sense of place you describe, but they are also attentive to the ways religion can warp lives — especially Kavanagh. “Clay is the word and clay is the flesh.” “The Great Hunger” is a poem that stuns me every time I read it.

Do you see yourself as having an overriding “project” in your poetry? You have been at this long enough to have a sense of what this may start to look like. It seems to me that Ark gives us some clues about this, but I am curious about how you might answer that question.

Right now, in my work, I feel a kind of movement between two different voices. My post as a city poet laureate since 2015 makes me think more about accessibility and having a kind of public voice. At the same time, much of my recent writing has focused on memory, and specifically on what I think of as hidden stories. Stories that are private and unspoken, written on the body, maybe, and the psyche. I’ve been writing some about time and memory, how we physiologically and psychologically experience time — the inconsistencies and inaccuracies of memory. And I’m thinking about unrecognized histories, secret histories. How can I use poetry to create an archive — I think that’s the right word — of queer feelings, repressed and hidden experiences.

So there’s this public voice writing poems about history and place, and there’s this private voice writing about hidden histories. I think a couple of the poems in Ark started me in this direction — poems where I used miracle stories from the gospels to reflect on my experience with my dad, juxtaposing the scriptural account with the hospice experience. A written account, an established story, and an intimate experience that belies or resists that story. So I’m thinking more about what gets recorded and what doesn’t.

I think before I wrote Ark, I would have said my “project” was a negotiation or an examination of the complicated relations between the sexual and the spiritual, and by extension the tension between identity and culture. What happens when the self you are becoming — or the self you are making — grows athwart the mores of your culture. I’m sure that’s still an integral part of what I do, if only because of who I am and where I came from. I think in my first book, Signals, I sometimes imagined that in terms of landscape — the land as a record of what has happened to it. I think I’m still interrogating the culture I grew up in and evaluating what to keep of it, but also what I’ve learned of resilience and empathy and self-making in gay culture. I think I’m still asking the same questions, but maybe in contexts that are different in scale.

Honestly, maybe I just don’t know yet what my project looks like, just that my more recent experiences with my family, especially the experiences of caregiving and death, are pushing me to think about the stakes of my questions in different ways.

Your publishing path has been varied — having published with three different houses over the years, Sibling Rivalry being the fourth. How has that affected your writing and your approaching this art?

Not having a publishing home makes for a kind of scrappiness and persistence. While I think of my books as coherent, I can imagine some would read them as quite different, in part because of the presses where they were published — a Southern university press, a gay men’s press, an Irish publisher, and now Sibling Rivalry Press, a press with a strong LGBTQ list but also one that thought of my book as a Southern story. My work has appeared in Southern anthologies, queer anthologies, Irish-American anthologies. I’m like a tree in a Wallace Stevens poem, I am of three minds like a tree in which there are three blackbirds!

Maybe it has affected how I put things together, or how and where I sent collections. Maybe Ark has a different kind of coherence because it is so focused on a specific time and place. I do wonder if having a publishing home would let me be braver, experiment more, but maybe it would also push me into one lane, one voice. I don’t’ know.

It has been almost a decade since you lost your father. How does it feel reading these poems again? As I recall, many of these poems were in draft form while you were in Arkansas nursing him. You wrote many of these poems in the midst of things. Conventional wisdom says best to allow some time and distance between trauma and the making of poems, but these poems seem to suggest otherwise. How do you enter these poems now?

Some were drafted there in Arkansas, and many of the others are based on a journal I kept while I was there. I think if I had waited to write about my experience, I could not have written as truthfully as I did. And frankly, I couldn’t have remembered many of the details. I had the time there to write, too. I kept a better journal there than I’ve ever been able to maintain before or after, maybe because it was a time and place set apart. I was cut off. The first several weeks, I had to drive fifteen minutes into the nearest town to go to McDonald’s and get on the Wi-Fi there to use email and to manage my classes back home. And for periods of time the roads were so flooded that only bigger trucks could get through. My world was that house. I was totally cut off, inside that house and inside my own head.

I guess it is conventional wisdom to allow some time, but maybe I would’ve been tempted to sentimentalize, or write what I thought my family would like rather than what I needed to write. Honestly, writing then and revising later let me put how I felt in the moment and how I felt afterward together. I think that’s really valuable, that combination, the rawness of the moment preserved somehow, but the ability to reframe it with what happens later and what I felt and thought later.

It is hard not to imagine that when you say in “Dogwood”: “I think my dead father is learning to love me. / Or I am learning to love him,” that you are speaking about poetry. Is this a misguided read of these very provocative lines?

I guess any poem can be autotelic in some way, about its own making. It’s the last poem in the book, so maybe the poem is about the way the book functions as a kind of reparative fantasy. That our relationship was healed. It was, but it wasn’t. I was there, but I wasn’t all there, or fully there. Or all of me was present there at his bedside and in that house, but not all of me was recognized. There were silences and awkwardnesses. I know there were unspoken things. I didn’t remember some people, and I also worried about how some people felt about me or about my being there.

When I wrote the poem, I had in mind John Lane’s dead father poems, in which his father comes back from the dead. There’s something healing in maintaining that relationship, that communication. The dead still speak. We still try to repair what has happened, what we have done.

You dedicate this book to your mother, but arguably it is your father who gets a lot of inches. Can you talk about how your mother sits at the heart of the collection?

The entire time I was taking care of my dad, I was also learning more about my mom. She told stories I’d never heard. I saw how she managed her life after a car accident, after dealing with my dad’s series of unidentified illnesses and hospital stays that ended with the diagnosis of cancer, too late. I saw how she managed her pain, physical and emotional. I call her the strongest woman I know. Because we were so alienated, I was not around after her car accident. I went to the hospital once, right after, and over breakfast in the hospital cafeteria, my dad started talking about how we needed to fix some things, and it quickly became clear that he didn’t want to talk about how to help my mom, he wanted to talk about fixing me. He wanted to fix me. I left.

So in some ways going home — I think I can say this now, though I wouldn’t have said it then — going home wasn’t just about taking care of my dad, it was about being there for my mom, whom I hadn’t been there to help care for. I was a bad son for her, because of the anger and alienation and shame that drove us apart, and I wanted to be a good son.

I also started to think about the complexity of her relationship with me. I remember watching Modern Family with her, and Brothers and Sisters, and there she was following a storyline with gay characters, laughing even at the jokes, sitting in a room beside me, her gay son, whose sexuality had been such a problem, a barrier, a sin. I saw how private she was, what she was willing to share with others and what she wasn’t. And that made me think about how difficult it must have been for her when people learned she had a gay son, especially in her church community. I started to put a poem about that in the book, but it felt tangential, I couldn’t find the right place for it. But for me, my relationship with her is the invisible thread the binds the book.

Image: Cloar, Carroll. “Alien Child.” 1955.

Kwame Dawes is the author of twenty-one books of poetry and numerous other books of fiction, criticism, and essays. In 2016, his book Speak from Here to There, a co-written collection of verse with Australian poet John Kinsella, appeared along with When the Rewards Can Be So Great: Essays on Writing and the Writing Life (Pacific University Press) which he edited. His most recent collection, City of Bones: A Testament (Northwestern University Press), appeared in 2017. Also in 2017, Dawes co-edited with Matthew Shenoda Bearden’s Odessey: Poets Responding to the Art of Romare Bearden (Northwest University Press). In 2018, a new edition of his 1995 epic, Prophets, was released by Peepal Tree. His awards include the Forward Poetry Prize, The Hollis Summers Poetry Prize, The Musgrave Silver Medal, several Pushcart Prizes, the Barnes and Nobles Writers for Writers Award, and an Emmy. He is Glenna Luschei Editor of Prairie Schooner and is Chancellor Professor of English at the University of Nebraska. He also teaches in the Pacific MFA Program. Dawes serves as the Associate Poetry Editor for Peepal Tree Books and is Director of the African Poetry Book Fund. He is Series Editor of the African Poetry Book Series, and Artistic Director of the Calabash International Literary Festival. In 2018 Dawes was elected a Chancellor for the Academy of American Poets and named a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.