I’ve always been fascinated by words in other languages. When I was younger, it was the way the words looked and the way they sounded more than the possibilities of their meaning. As a child, I’d pick up my father’s copy of Le Petit Prince, put on my best French pronunciations, and read pages out loud without comprehending anything but pure sound.

In 2016, I spent a month in Greece and took Beginning Greek language lessons. In our first class, we memorized the Greek alphabet. Once I understood the sounds and symbols, the world outside came alive; every restaurant banner and street sign begged to be decoded. Likewise, my love for Dutch that I studied for three years at the University of Michigan was sparked by none other than the words open keuken beneden, which means “open kitchen beneath” — a meaningless statement to anyone not buying an Amsterdam flat, but the unfamiliar diphthong, the dip of the voice’s pitch, the cutting off of the “n’s” at the ends of the words, was thrilling to me.

There’s something about learning new words that feels like a dive into a fantasy world; like cracking another universe’s enigma code; like stepping through a brilliant blue portal into a realm of knowing. The practice of learning new languages is a humbling exercise. The act transports you back to your toddler self, vulnerable to mistakes; at once you are morphed into a Socratic state of awareness that you have so much more to learn. Which brings me to Ella Frances Sanders’s book Lost in Translation: An Illustrated Compendium of Untranslatable Words from Around the World, a book that provides a contemplative space to consider how others experience and label the world.

There’s something about learning new words that feels like a dive into a fantasy world; like cracking another universe’s enigma code; like stepping through a brilliant blue portal into a realm of knowing. The practice of learning new languages is a humbling exercise. The act transports you back to your toddler self, vulnerable to mistakes; at once you are morphed into a Socratic state of awareness that you have so much more to learn. Which brings me to Ella Frances Sanders’s book Lost in Translation: An Illustrated Compendium of Untranslatable Words from Around the World, a book that provides a contemplative space to consider how others experience and label the world.

Given to me as a gift because it was about “words” and everyone close to me knows I’m a word-lover, Sanders’s book has become an essential text in my life; one I revisit again and again. Released in 2014 by Ten Speed Press, Lost in Translation is a printed book that contains fifty-two original drawings featuring a mixture of humorous, culturally significant, and poignant foreign words that have no direct translation into English. By direct, I mean a one-to-one translation, such as “perro” means “dog.” Instead, each word concisely describes a phrase or feeling that we have no exact word for in English.

From the Farsi word for the twinkle in your eye when you first meet someone, to the Swedish word for the road-like reflection of the moon over the ocean, to the Greek term for pouring yourself wholeheartedly into something, to the Welsh word for a sarcastic smile, Sanders illuminates words across a global spectrum of life experiences. She reminds us that language, above all, is the element that defines our humanity.

From the Farsi word for the twinkle in your eye when you first meet someone, to the Swedish word for the road-like reflection of the moon over the ocean, to the Greek term for pouring yourself wholeheartedly into something, to the Welsh word for a sarcastic smile, Sanders illuminates words across a global spectrum of life experiences. She reminds us that language, above all, is the element that defines our humanity.

The provision of a word, a moment, or a philosophy to meditate on is something we often need, especially in a world constantly bombarded with high-speed, flashy, and shorthanded communication. Although we now have the capacity to rapidly connect with others, the potential for flat emotions, misread intentions, and gaps between meaning and interpretation are still as present as ever. Sanders proves that slowing down and exploring the world around you from another language’s point of view is an invaluable resource for living well, and perhaps for poetry-making, too. For example, Sanders says of the word wabi-sabi:

Derived from Buddhist teachings, this is a Japanese aesthetic centered around discovering beauty in imperfections and incompleteness. An acceptance of our transience and the asymmetry within our lives can lead us to a more fulfilling yet modest existence.

Derived from Buddhist teachings, this is a Japanese aesthetic centered around discovering beauty in imperfections and incompleteness. An acceptance of our transience and the asymmetry within our lives can lead us to a more fulfilling yet modest existence.

As someone who constantly berates herself to achieve perfection in as many parts of her life as possible, I couldn’t help but feel comfort in wabi-sabi the other day when I sat down to type at an old-fashioned typewriter. With no delete button at my disposal, all my spelling errors and first-draft thoughts were staring back at me, displaying my brain processes in a terrific livestream. For the first time in a long time, I found that the mistakes were not mocking me. They were who I was in that moment. Just like the time capsule of daily poems I drafted for National Poetry Month in April, these typewritten imperfections showed me in my rawest, unedited form, and it really was beautiful.

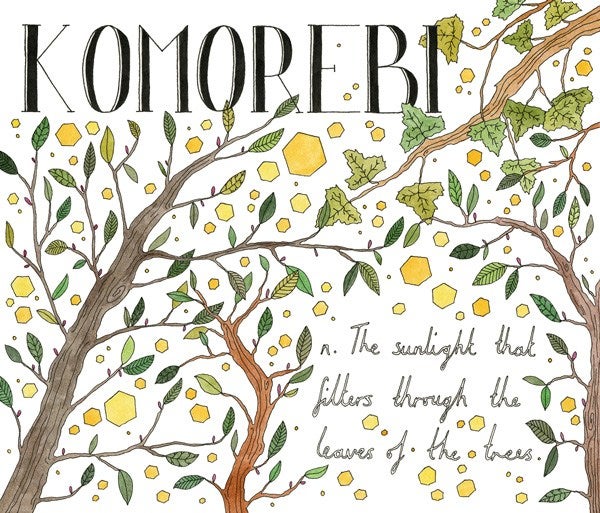

In addition to allowing readers to reflect on their own life, the words in Sanders’s book invite readers to consider, as posited on Mind Pickings, whether a culture lacking a word for the sunlight that filters through the leaves of trees is also a culture lacking the dignified ability to be unshakably present, to appreciate the stillness and slowness of nature’s infinite orchestra. Sanders shows that the words making up any given language supplies a telling glimpse into a culture’s priorities and values. Sanders says in the book’s introduction:

In addition to allowing readers to reflect on their own life, the words in Sanders’s book invite readers to consider, as posited on Mind Pickings, whether a culture lacking a word for the sunlight that filters through the leaves of trees is also a culture lacking the dignified ability to be unshakably present, to appreciate the stillness and slowness of nature’s infinite orchestra. Sanders shows that the words making up any given language supplies a telling glimpse into a culture’s priorities and values. Sanders says in the book’s introduction:

The words in this book may be answers to questions you didn’t even know to ask, and perhaps some you did. They might pinpoint emotions and experiences that seemed elusive and indescribable, or they may cause you to remember a person you’d long forgotten. If you take something away from this book other than some brilliant conversation starters, let it be the realization (or affirmation) that you are human, that you are fundamentally, intrinsically bound to every single person on the planet with language and with feelings.

The poet Matthew Dickman is known to denounce the idea of individualism: “Individualism is a lie. We are not special, we are not unique. Individualism is a warmer, cozier substitute for the self, which is unknown and therefore dangerous.” Along the same lines, Sanders agrees that “we are all made of the same stuff…. We laugh and cry in much the same way, we learn words and then forget them, we meet people from places and cultures different from our own and yet somehow, we understand the lives they are living.”

The poet Matthew Dickman is known to denounce the idea of individualism: “Individualism is a lie. We are not special, we are not unique. Individualism is a warmer, cozier substitute for the self, which is unknown and therefore dangerous.” Along the same lines, Sanders agrees that “we are all made of the same stuff…. We laugh and cry in much the same way, we learn words and then forget them, we meet people from places and cultures different from our own and yet somehow, we understand the lives they are living.”

In Sanders’ world, we’re all included. We know the feeling of butterflies snowglobing in the stomach when we feel nervous or in love (kilig; Tagalog). We’ve experienced the disappointment of arriving at an untimely comeback after the conversation has long been over (trepverter; Yiddish). Everyone has heard a joke so terribly ridiculous that laughter was inevitable (jayus; Indonesian). Maybe, at this exact moment, a man in Australia and a woman in Chile both sit at the water’s edge with boketto in their eyes, thinking about nothing specifically. Sanders invites us to think mindfully, both about our own experiences and of those belonging to others around the globe, and to consider the similarities that connect all humans to each other.

Images via ellafrancessanders.com.