Fiction by Jenny Irish from our Fall 2017 issue.

At the end of a dirt turn-around, a dog walker loses hold of his shepherd and watches, helpless, as it pelts away. Fingersnap — that quick, it’s out of sight in the trees, disappearing through speckled alders that grow down a steep embankment to flourish in swampy land below.

The dog walker calls, “You! You!”

But it’s already going at something. Sound carries. Digging. Whining. The man rolls his pant cuffs and plunges down the slope. More sliding than walking, he leaves behind a flattened swath. As he skids toward even ground, the air fills with something white and weightless lifting on the wind.

It isn’t snow; a float trails across his cheek without a sting. A bit catches in his hair. He pulls it free. Rubbing it between two fingers — soft — he makes a quick determination: down. Cursing, he flicks it away. Cold mud slops his cuffs. Forced to move slowly, he swears again with feeling.

He expects the dog to have a bird.

What he discovers is a child.

A girl.

Locked in the ice, her pale hair is spread all around her, and the dog, digging at her narrow back, shredding the nylon shell of her jacket, churns curls of down into the air.

~

They meet like anybody meets. Pressed, he could not say for certain where he was, or what it was he was doing the first time that he saw her, or even what first words were exchanged between them. (He would place equal bets on hey and hello.) Through common coincidence, small town eventualities, their paths cross and cross until they are entangled. On occasion, they drink beer in the same pine paneled bar. In the back, he plays darts against himself. Near the front window, bathed in white winter light, she sits at a high-top table, eating maraschino cherries from a little porcelain bowl.

They arrive at the same places, a slivered moment apart and they end up passing through doorways like a couple — as if they’ve run out together to pick up milk and bread to share — though they are still strangers. From afar — as the expression goes, though often there is little physical distance between them — he admires her.

Once she pulls into a driveway behind him at the instant he’s cutting his motor. They make small talk walking to the door of the house of a mutual acquaintance. The porch is bedecked in lights, pulsating with holiday cheer. It’s brutally cold. His fingers are still curled, locked into the shape they took around the steering wheel. Needles of snow prickle against his skin, and he’s hurrying to be out of the weather, and her nose is red from the cold, and she’s sniffling, and the colored lights blinking in the bushes and wrapped around the porch rail splash her face unflatteringly with green and blue and red, and all her blonde-white hair is tucked up under a fisherman’s beanie. He doesn’t realize until they are inside and separated that she is the woman whose proximity has, for some time, stupefied him.

In his throat the missed opportunity lodges as physical pain. Like a fishbone, it’s sharp-edged when he swallows.

A dozen small groups of conversation have formed. He floats, flotsam, nothing to add. In the far corner, she’s dancing by herself, eyes closed, twisting her hips and shaking her hair. She’s crowned herself with a loop of garland. When she shimmies, her sweater pulls up, showing the tender declivity at the base of her spine. He understands that only her looks save her from embarrassment.

To continue reading “Worry,” purchase MQR 56:4 or consider a one-year subscription.

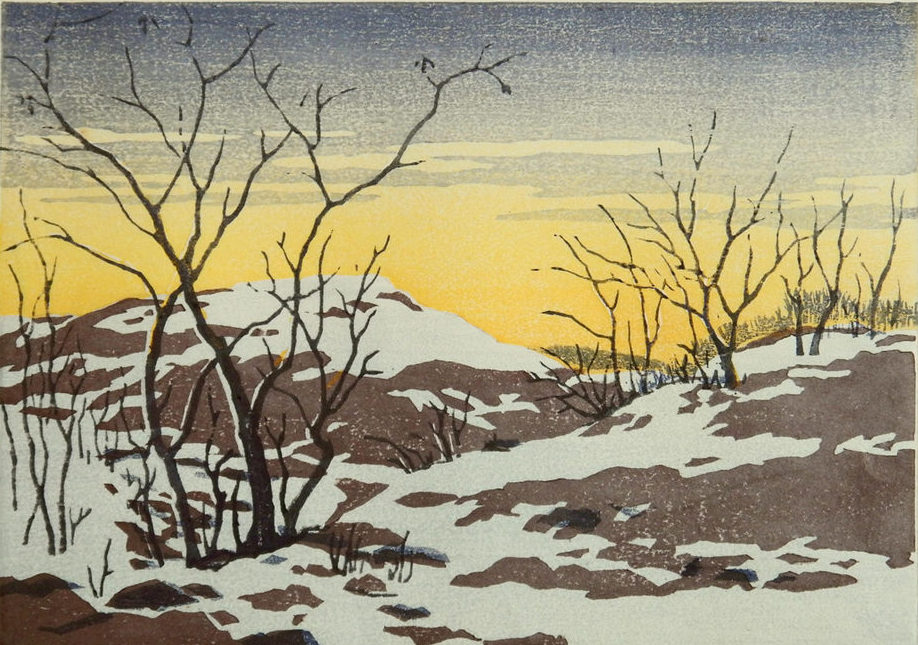

Image: Bassett Hall, Norma. “Winter Sunset.” 1943-44. Color block print.