Nonfiction by William Klein for MQR Online.

It’s a certain kind of fishing season where you’re glad the salmon aren’t showing because you couldn’t catch them if they did. Summer of 2016 was such a season for me: my skipper had leased a new boat, the Ultimo, and we left Seattle in a sunny but chill May, turning off our cellphones before entering Canada on our way to Alaska. Rounding Pt. Gardner before Sitka, I discovered Ultimo’s fiberglass hull made it corky in storms, rendering me seasick like our old boat, a wood and steel junker, never had. The old boat had sunk during a previous season, though, after striking a reef south of Sitka in the night. Ultimo had problems—like a hydraulic system on hospice, or a cochlea-ravaging alarm that went off for no reason, its wires leading nowhere—but it was above water.

This was my eighth season with my skipper but my first following a three year hiatus to get my MFA in fiction. I’d grown up on an island in Alaska, spending my twenties shoring up a bachelor’s degree during the winters while deckhanding during the summers, afraid to even acknowledge my lifelong desire to be a writer until applying to fiction programs. When I got into my top choice, the University of Michigan, I cried for minutes on end, in front of my cat, who did not care. All those pre-sunrise basement hours with my laptop and a pot of coffee. All that work, all that hope. In Ann Arbor I met my cohort, who had attended elite eastern schools, taken workshops with Joyce Carol Oates. One guy had been shortlisted for the Man Booker in his third year. Somehow they were the first people who spoke my language. I wanted us to always be sharing a big bed, lazily kicking for the covers, but they also made me feel like a hick.

I learned and changed so much in two years at Michigan that I felt bloated by all I’d taken in; soon I would rip open. Gifted a fellowship following graduation, I finished an initial draft of my novel—about Alaska and way too long—then dallied for months with research. I picked at stories from my thesis. For my first Michigan workshops I’d written passionate, out-there stories adapted from poems or featuring Captain America, but they’d been met with disappointingly grounded comments about structure, character arc, tension, and point-of-view. During my second year, I wrote two-character domestic stories that at least let my professors respond to my work without asking what it was “doing.” This was compromise–it was being an adult. I changed my writing style, and changed it and changed it again, and changing hurt, but learning hurts, right?

Right? Or had I given away what had brought me there? Did it even matter? Unable to answer these questions, I was wasting time.

My listless winter concluded with my skipper’s call, offering back my old job. I poured what would be my life for the next six months into two 45-liter backpacks. One held old fishing clothes, my sleeping bag, phone chargers, scale-shedding boots tied to the outside. The other? Books. Only books I’d read before my MFA. Among them: Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville. Gravity’s Rainbow, by Thomas Pynchon. Middlemarch, by George Eliot. Each was well-feathered with sticky notes, margins scribbled with thoughts, lines pressed by my pen like lines of light pressing my face into film. Each a snapshot, then. Rereading these books would be a way to confront who I’d been before my MFA, assess what I’d given away, and collect what I needed to move forward.

~

In Sitka we began the preseason work of sewing up holes in our seine, the quarter-mile net towed in a crescent between Ultimo and our skiff to catch salmon. By June we were ready for test-fishing, although that went poorly. I fucked up basic details the first time we set our seine, and was chewed out by my skipper. Next set our skiff’s engine committed seppuku, bowels of springs and cogs shearing into an oily salad revealed upon autopsy in Wrangell. The other crewmembers disagreed with my skipper’s propensity for chewing ass and were discouraged by the weeklong wait for replacement parts from Seattle—precious time during a summer season—so they quit.

I retreated into books, old escape. Ishmael shrugging off doom as he boards the Pequod. Ahab defying God in his mad hunt for the white whale. On my original reading, I’d been almost upset by how good Moby-Dick was—so funny, so weird—why this reputation as an obligatory tome? Post-MFA, I enjoyed the boldness of Melville’s instructions on the nobility of whaling, the dangers of obsession. Workshop stories had been “about” their topics in the physical sense: in the vicinity of, with uncertain relation. Melville wasn’t afraid to write directly.

As a writer, language had been my first love, something I was reminded of by my notes. I think this is true for most writers: when we learn to put one word after the other we can’t imagine anything beyond the glory of those little births. Hubris is involved. And that guy, the one who filled Melville’s margins? Goddamn did he love language. He loved it absolutely. He loved bold pronouncements and Homeric similes. Chapters like “The Line” or “The Try-Works” inspired underlines sprinting whole paragraphs, stamina zooming them to the next page. On my second reading of Moby-Dick, I realized that before my workshops at Michigan I’d hung my writing identity on language’s unbound rampaging creation. I’d questioned the power of language though, when I’d written those sober, domestic stories during my MFA’s second year, and my love had become no longer absolute. My distance from the rapture in those old notes felt like the distance between shore and the Ultimo’s deck, me looking at a landscape I no longer fit into.

The fisherman I’d been felt distant, my basic mistakes during that first set humiliating. Not for three grad-school dense years had I labored fourteen, eighteen hours daily, or been addressed in non classroom-appropriate tones. In Ann Arbor, I’d been known as “the Alaska guy,” which now felt like a pose. Feeling too Alaska for the MFA book-world had supplanted how much of my life I’d felt too book for Alaska. Maybe that was why I’d been unable to progress on my novel. I’d left this place, after all. Had I ever really loved it, or just the way it let me represent myself?

The replacement parts appeared, accompanied by fresh crew. A meth-head I hid my wallet from. A skiffman prone to recounting fights he’d won, and also to violent tantrums. Still another was a common type in Alaska, the free spirit looking to grow her soul on the waves, convinced hard work would cure her equilibrium destroyed in a car crash the previous year, which she revealed when my skipper asked why couldn’t she even stand the fuck up? Our worthless crew didn’t matter, though, because Ultimo’s hydraulic clutch finally cremated itself fishing the vicious tides of northern Chatham Strait, preventing us from bringing in our seine. After that was fixed, our refrigeration system turned out to be full of acid—our best guess was the coolant had become contaminated—leaving us hamstrung since we could only fish where ice was available to chill our hold, whether salmon were there or not. The replacement crew quit and were replaced in turn. We entered the back half of July.

~

In one chapter of Gravity’s Rainbow the hand of fate rearranges the stars to flip off protagonist Tyrone Slothrop, for whom I suddenly had a lot of sympathy. Recounting Tyrone’s journey from London to post-World War II Germany hounded by shadowy forces, Gravity’s Rainbow is a madcap, hallucinatory, rocket-haunted, postmodern singalong, every page a linguistic feast. My notes from my first read show someone giving himself over to the trip, stunned and in love but unsure with what. On the second read, as Ultimo sulked through the waters of the Inside Passage, Gravity’s Rainbow was entirely different. The plot felt downright ascertainable, the chessboard of characters comprehendible, the book even more brilliant. And yet. Wasn’t I just a little … bored? Come to think of it, hadn’t I been bored rereading Moby-Dick, as well? Sure, I could now track how Pynchon accomplished movement using liminal spaces (thanks for that term, workshop!) and I felt that, if nothing else, my MFA taught me to understand him better. But my MFA also made me pick my favorite books apart, how they used curses and conspiracies to deny agency, pitting characters against their authors, an arguably uninteresting fight. I didn’t blame the books: they acted intentionally, brilliantly. Instead, I blamed myself—why was I reading like this? It wasn’t just that I was reading these books a second time, since plot had never been my attraction. Had I come away from my MFA with nothing but a need to dissect, knowing how heart and liver worked together but no longer convinced the result was worthwhile?

Fishing crews are always doing a kind of group-participation math: someone adding up the fish tickets, another calculating what our expenses might be, the skipper estimating the strength of first the dog salmon and then the pink runs, and everyone applying their crewshare (usually ten percent) to the relayed total. The salmon finally came in, but always in places too remote for the ice-boat umbilical that kept Ultimo haunting Sitka. As our season shifted toward its last month, we gave up hopes of bonanza paydays and instead resolved to make more than a summer working at McDonald’s, grinding out long days on what salmon there were. I wrote Pynchonesque songs to distract myself:

“August (Lullaby for a Bad Season)”

It’s Au-gust so I-guess

Our season’s nearly through

The dogs have all gone now

The pinks wave adieu

Our fishhold is empty

We barely caught a few

I’ll stop dreaming of paychecks

Start dreaming of you.

“You” meaning my girlfriend. The Alaskan summer ceded half-lit nights to the moon again, stars MIA since April now like spilled sugar. One late wheelwatch I saw the northern lights. I had finished Gravity’s Rainbow, rediscovered the ending, how Slothrop literally fades into nothing. It was an option. I realized this while watching the slow-floating aurora, green like nothing on earth but not like nothing in nature. I didn’t have to be a writer. I had made it through this season, sometime during the summer I had forgotten to worry about whether or not I fit into Alaska, and living as a commercial fisherman was tempting. Three years ago I’d followed writing all the way to Michigan, tried harder than anyone could ask, as had my girlfriend. Graduate school is hell on relationships if you don’t know, although fishing seasons are no picnic either. My girlfriend had never asked me to stop writing, but how could I make her suffer indefinitely as I chased this dream? Having given up my absolute belief in language during my MFA, I had given up other absolute beliefs about writing, like the short-lived but fierce conviction I could never do anything else with my life.

Middlemarch’s plots revolve around characters having big dreams, then realizing they must either compromise or see their dreams destroyed. These confrontations coincide with challenging marriages, in which the infatuations of courtship must give way to loving the day-to-day details of their partners. Everyone should read Middlemarch because it will make you a better person—a sentiment we would call embarrassingly didactic in workshop. As Ultimo prepared to travel south in September, I saw parallels between myself and Middlemarch’s Dorothea, although her naivety and idealism led her to a disastrous marriage instead of graduate school. Eliot’s language is wittily gorgeous, if less dazzling than that of Moby-Dick or Gravity’s Rainbow, but as I reread Middlemarch I was surprised to find my notes more about the character and empathy pervading the book than just the prose. Eliot lets every character make their own mistakes, her world promising this time everything might work out, which kept me engaged. She accomplishes this by foregrounding things like character and narrative tension—the day-to-day of writing my MFA professors had pushed, the things I had painfully changed my writing style to learn, the deeper love I needed since infatuation had faded. My life had been wandering, tumultuous, and trying to be a professional writer was unlikely to change that; but writing allowed me to wrestle my obsessions with the ugliness and beauty of Alaska and make something I’d never find in the z-axis: a place where my two worlds lived together.

~

Ultimo limped back towards Seattle with a worrying leak. We had made little money, although more than our nemeses at McDonald’s. On the third day of the week-long trip which offered little distraction besides talking and watching the scenery pass, my skipper recounted the grisly afterlife of our old wrecked boat—crushed in a landfill, salvage sold to pay for burial. I felt upset. I had given that boat my twenties and had naively felt my sacrifice ensured buoyancy. But with that comfortable old deck under my boots I might have found it easier to let writing go than confront day-to-day compromises of my lifelong desire, a trap I’d already slipped into during my fellowship.

Through southern British Columbia we coughed on smoke from wildfires, tying up at Fisherman’s Terminal in Seattle before sunrise, the pilings strung with enormous mottled spiders. The smoke had given us gravelly throats and red eyes. We scattered off Ultimo in case it sank. After so long at sea, land and kept staggering as I walked. My two backpacks made my shoulders ache, but they balanced me.

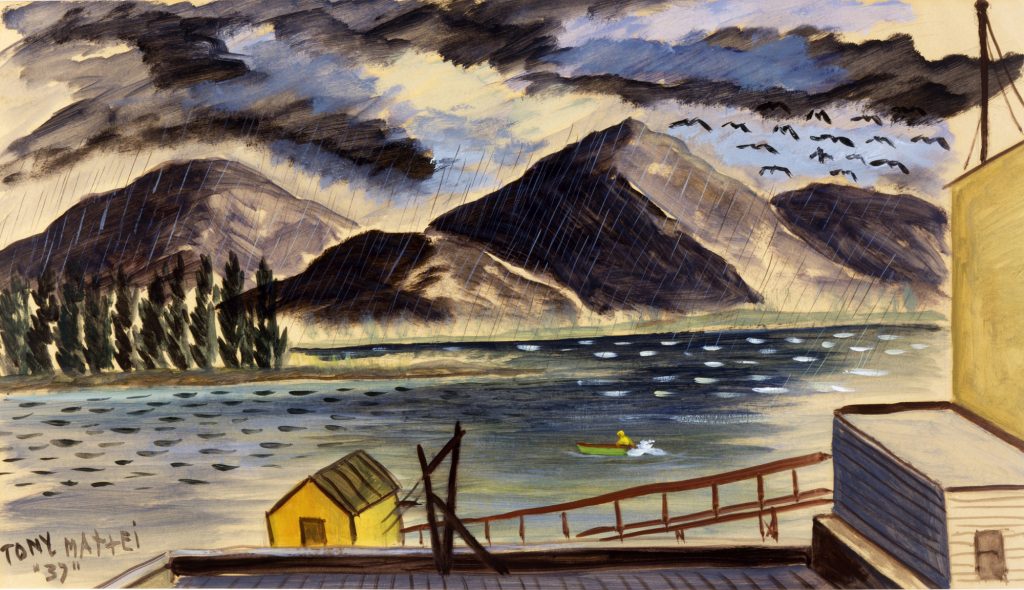

Image: Mattei, Tony. “Rain, Ketchikan, Alaska.” 1937. Watercolor, oil, and pencil on paper. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

Image: Mattei, Tony. “Rain, Ketchikan, Alaska.” 1937. Watercolor, oil, and pencil on paper. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

William Klein’s short fiction has appeared in West Branch Wired, Pacifica Literary Review, and Carve Magazine, which nominated his short story “Children’s Home” for a PEN Debut Short Story Prize in 2017. He was raised in Ketchikan, Alaska and worked for eight years as a commercial fisherman. He received his MFA in fiction from the University of Michigan in 2016.