On the dedication page for Henry Hart’s recent biographical work, The Life of Robert Frost: A Critical Biography, we find a quote from Yeats: “The intellect of man is forced to choose / Perfection of the life, or of the work.” Using it as the book’s guiding principle, Hart may be provoking us to ask whether those, like Frost, who “perfect the work” should also be expected to “perfect the life.” But is such a choice even possible, given that life and work often overlap, privileging neither camp?

Hart’s monumental volume about the most honored poet in American history tells the good, the bad, and the ugly in just proportion. Alongside accusations of Robert Frost’s selfishness and cruelty by intimates, his verbal offenses to friends and colleagues, and a hubris that angered even President Kennedy, for example, the poet demonstrated a loving paternal side. With his wife, he homeschooled his four children and generously supported their adult businesses; he saw to his sister’s care in her long illness, and mentored his students well beyond graduation. As an Honorary Consultant in the Humanities at the Library of Congress, he likely inspired into being the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. And, of course, his poems are replete with evidence of attachments to nature and people.

Hart’s monumental volume about the most honored poet in American history tells the good, the bad, and the ugly in just proportion. Alongside accusations of Robert Frost’s selfishness and cruelty by intimates, his verbal offenses to friends and colleagues, and a hubris that angered even President Kennedy, for example, the poet demonstrated a loving paternal side. With his wife, he homeschooled his four children and generously supported their adult businesses; he saw to his sister’s care in her long illness, and mentored his students well beyond graduation. As an Honorary Consultant in the Humanities at the Library of Congress, he likely inspired into being the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. And, of course, his poems are replete with evidence of attachments to nature and people.

Equipped with new biographical discoveries, Hart resists the temptation to demonize this difficult man. If Frost’s worldview was tinged by fatalism, Hart tempers the blame with compassion. Consider the poet’s entrenched Puritanical mores, or the fact that he was orphaned as a boy by a high-strung, abusive, alcoholic father. Consider the poverty he carried into adulthood, or the mental illness that afflicted not only Frost but also his sister and three of his children. Miseries aside, the poet’s ambivalence toward Native Americans, his support of slavery, and his bigotry toward African Americans and the Chinese are not whitewashed. Nor does Hart conceal his resentment of his grandfather for giving him gifts of money and property—without which Frost’s poetic career would not have thrived.

To champion a holistic view of Frost, Hart takes readers on a journey spanning more than three hundred years of family history. It begins in seventeenth-century New England, where the poet’s ancestors fight both the Indians and the British—the same region from where Frost’s father would later attempt to defect to the Confederate Army. Following Frost’s parents’ marriage in Pennsylvania, the pair migrate to San Francisco, where the poet is born and learns at the knees of his Swedenborgian mother. Following the death of his father at age eleven, the family resettles to New England, where the poet goes to school, teaches, marries, attends Harvard, teaches again, and farms. In 1912, with his wife and four children in tow, Frost boards a ship to Great Britain, where he secures a publisher for his first book, A Boy’s Will. He returns with his family by ocean liner in 1915, just three months before the German U-boat’s attack of the Lusitania. Between hectic teaching and speaking engagements that send him far and wide (including three extended visits at the University of Michigan), he involves himself in both the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations, contributing to America’s cultural and political life that ends with an ambassadorial mission to Russia in 1962.

Of course, no portrait of a poet is complete without the poems. Hart, a poet himself, deftly weaves Frost’s most salient verses throughout the text. He selects lines, for instance, from “The Road Not Taken,” which figures as an important thread in Frost’s development. If the poem pictures the solitariness of his poetic path, Frost—who would take the “[road] less traveled by”— could not have said it better. A formalist who cleaved to the disciplines of rhyme and meter, Frost resisted the prevailing Pounds and Eliots of his day and “[would] as soon play tennis with the net down as write free verse.” More importantly, perhaps, he depicted a regional people’s universal longings as no American poet had done before, in ordinary language. Hart writes: “The hardships encountered in love, in family, and in everyday work on hardscrabble New England farms compel Frost’s pastoral characters to find solace in transcendental pursuits. ‘I only hope that when I am free,’ Frost says in “Misgiving,” that ‘[I] go in quest / Of the knowledge beyond the bounds of life.’”

Frost would sometimes reference “The Road Not Taken” in later poems, pleased with the title’s ambiguity. But Hart seems to suggest that the narrator did not choose the road less traveled for its own sake, but because making a choice was necessary, even manly. In fact, the poem was partly motivated by his concern for writer Edward Thomas, an Englishman, who wavered between staying home to create poetry and enlisting in the British army. Prodded by the famous poem and conceivably to please his friend, the thirty-eight-year-old Edward donned the military uniform. His death in France three years later would bring Frost to tears.

Frost’s own favorite poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” also receives special consideration. It recalls the aftermath of his disappointing trip to Derry Village to sell eggs in order to buy Christmas presents for the children, when he pauses during his sleigh ride home, dejected, through “lovely” woods. Hart writes, “Although he told different stories about [its] meaning, the poem itself points to a familiar conflict in Frost’s work between the desire to give up and the desire to persevere. The dark New Hampshire woods . . . exude a seductive, potentially fatal attraction. If the man on the sleigh were to wander into the woods without proper survival gear, he would quickly freeze to death. Out of a sense of duty to his family, career, and horse on the ‘darkest evening of the year’ (the winter solstice), Frost’s brooding narrator resists the siren call of the trees . . .” Emotionally vulnerable, the poet is loathe to be caught in his morbid mood by the owner of the woods, and also worries that his horse “must think it queer / to stop without a farmhouse near / between the woods and frozen lake.” Although the reiterated “And miles to go before I sleep” in the last quatrain darkly resonates with “the traditional association of sleep and death that appears in many of Frost’s poems,” the poet chooses life over death.

The New Englander’s bias toward “the perfection of the work” did not, it appears, curtail his passion for living. That Frost persisted as an unknown poet for twenty years, suffered privation, and kept at bay his lifelong paranoia and depression is a study in courage. Although the adventurer pursued his less traveled roads through many a winding way, Hart handles the poet’s peregrinations with a quick-paced pen that neither cheats the details nor inflates the finer points. With an impartiality born of extensive research, Hart reveals a three-dimensional man whose imperfection of the life “has made all the difference” in American letters.

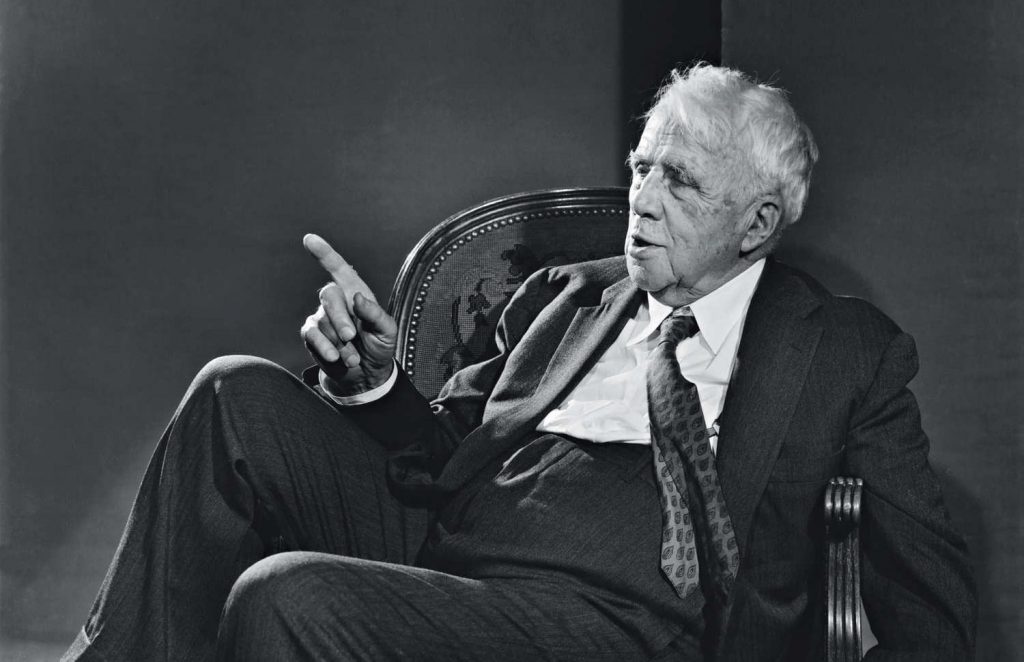

Lead image: Frost in 1958. Photo by Yousuf Karsh.

Anna Evas’s poetry and non-fiction have appeared in literary and medical publications. She makes her living as a musician.