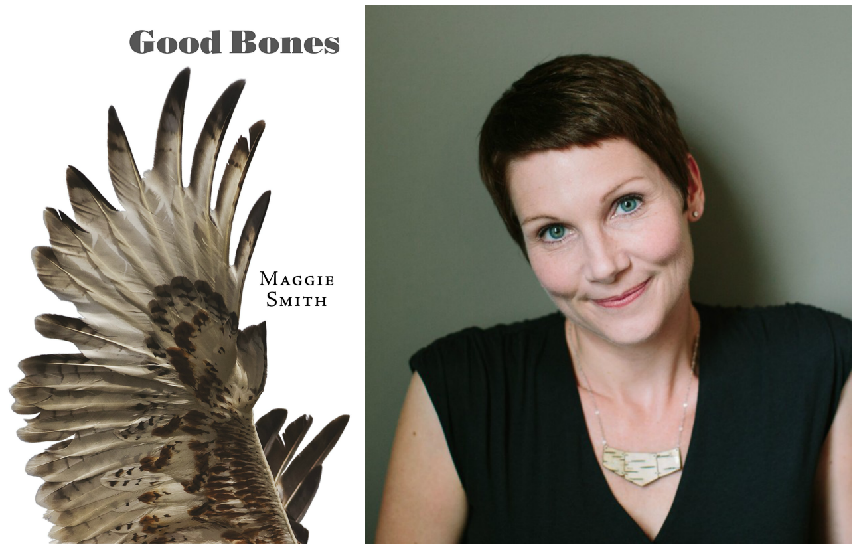

With Good Bones Maggie Smith gives us a collection of poems, “…each one an empty / locket with space inside it, but for what?” (From “The Hawk.”) The book explores the “invisible surround,” interpreting how things become what they are and learning to live with and love them, especially when it’s challenging:  “Face it, your life / is not what it was” and “…pressed to the earth in a place // you called nowhere because there was nothing / to fence in” (from “This Town”).

“Face it, your life / is not what it was” and “…pressed to the earth in a place // you called nowhere because there was nothing / to fence in” (from “This Town”).

The truth of these poems flies out of the honesty and realness of Smith’s experiences, her language richly accurate, deep and yet readable as if it were our own thoughts written down, brimming with feeling, and attuned through imagination’s watery grasp. Good Bones is angled on listening for the lesson, not creating it. Knowing we cannot outgrow our shadow, Smith writes toward an enlarged intimacy with the troublesome: “the world is at least / fifty percent terrible, and that’s a conservative / estimate” (from the poem in which the book gains its title, “Good Bones.”) It is as Gauguin referred to it in his own practice, focusing on the “dark unknown corner of the self.”

Smith, with the effervescent presence of her children, brings forward ancient knowledge into a new fraction of light: “Already she knows loving the world // means loving the wobbles / you can’t shim, the creaks you can’t // oil silent…” (from “Rain, New Year’s Eve”). We try in so many ways to order the world, but daily we are bombarded by the reality of external forces, the ordinary things that demand our attention, calling us away from the drawing board. Still, Smith retains her aesthetic awareness even in what may seem the most mundane. Her poems are steeped in an herbal tonic that helps and heals when we are looking at what is beyond us and cannot quite grasp things on our own. It’s like the spirit here is moving through the world with the homing instinct of an echo. Her vision is a sort of balm, her voice meditatively clear and profound.

These lines, for instance, regarding a child’s ability to ground us, come to mind: “Of everywhere / I’ve lived, this is home // because my daughter / draws it…black // pluses for windows…” (from “London Plane”). Not only is the sensibility here aware of the homing nature within being a parent, but is given depth with the “black // pluses for windows…” suggesting that the addition of perspective to the world is our innate and endlessly righteous work.

The subtle mark of Smith’s excellence is how each poem arrives where it’s at — meeting both itself and the world, inhabiting them at once and entirely. The poems wander, examining the reflexive nature of our human, animal, moral and ethical mind, but by the final line they come fully into themselves. This mark is Smith’s capacity for hearing and feeling how the poem is in communication with the world through its various parts, and conveying with control and yet enough sense of wonder this contract with the world, self, and language. But, there are shadows, and Smith does not shy away from them. For example, from the poem “Panel Van”: “This morning // I told my daughter the one about still loving / the world we live in, the world the man / lives in, lost. Yes, the same world.”

The subtle mark of Smith’s excellence is how each poem arrives where it’s at — meeting both itself and the world, inhabiting them at once and entirely. The poems wander, examining the reflexive nature of our human, animal, moral and ethical mind, but by the final line they come fully into themselves. This mark is Smith’s capacity for hearing and feeling how the poem is in communication with the world through its various parts, and conveying with control and yet enough sense of wonder this contract with the world, self, and language. But, there are shadows, and Smith does not shy away from them. For example, from the poem “Panel Van”: “This morning // I told my daughter the one about still loving / the world we live in, the world the man / lives in, lost. Yes, the same world.”

Smith suspends the heartfelt moments among such fast passing times and splits them open, electric, and makes a tunnel of understanding “the precise size and shape of [the] body” so we may hold it, carry it with us, and contemplate with devoted attention, and come to know ourselves and what we love a little better. From “Let’s Not Begin”:

If I list everything I love

about the world, and if the list

is long and heavy enough,

I can lift it over and over—

repetitions, they’re called, reps—

to keep my heart on, to keep

the dirt off.

Good Bones is a series of repetitions, a poetic time capsule of things loved, lifted over and over again, dirt made visible, and the poet’s heart on and on and on. And it is this quality, this love, the difficulty and praise of it, the “on-ness” that sets this book among the finest collections where, as readers, we can feel “only sunlight strumming / the tether between [us]” (from “The Hawk”).