I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about what it means to return to something. A place, a project, an idea, a feeling. Around this time last year, I was in the process of moving back to my hometown to teach creative writing at my old high school. I was in a good position, objectively speaking. I was heading to a city I knew, moving in with my partner, moving closer to my family. I was taking a job I really wanted. But I didn’t feel good at all.

The fact that I’d be working at my old high school scared me shitless. It’s a public performing arts magnet program, one of the Top 50 in the country, which sounds great, but I had just enough experience working with teenagers to know they’re merciless bullshit detectors. I also remembered how my classmates and I had treated some of our teachers — teachers who would now be my colleagues.

But I’d chosen this job, even given up a measure of economic security for it: the same week I got an offer from the high school, I also received an offer to teach composition at the University of Michigan. Both were adjunct positions (yes, you can be an adjunct at a public high school), but the Michigan job offered benefits and I’d earn, in one semester at Michigan, the same amount I’d earn during an entire year at the high school. Here’s the thing, though: Michigan couldn’t guarantee that I’d be rehired the next semester. The high school job would be mine as long as I wanted it. And I wanted that job in a bone-deep way I couldn’t fully explain. When I thought about turning it down, I felt profoundly sad, like I was failing myself.

The high school job wasn’t the only thing scaring me, though. When I moved back to Pittsburgh, I hadn’t written in almost six months. I had just completed my third and final year at Michigan’s MFA program. I’d spent ninety percent of that time finishing a novel, which I’d failed to sell. I was sort of pinning all my career hopes on this book (which was an egotistical and idiotic gamble, but also one that fiction writers are encouraged to make). I felt like a total failure. Like I was maybe not qualified to teach anyone anything.

*

There’s this idea — so prevalent that it can feel like gravity or oxygen — that your worth is defined by what you produce. I am currently producing this blog post. This blog is connected to a respected literary journal. I can point to this piece and say, Look, I’m a real writer. I have proof.

What does it mean to be a “real” writer? For a long time, I would have said it meant someone who writes stories or poems. I also would have thought (but not said out loud, because I’ve always known that my faith in prestige is gross) that being a real writer meant being attached to a university and/or major publishing house, some vast, ensconced body of people who implicitly or explicitly approved my work. But I’ve never believed that approval was the most important part, even if I do find it scarily addictive. The writing part was the most important.

So if I wasn’t writing, by my own definition, was I still a writer?

*

I’m not going to get into the details of my first year teaching high school (my students are Google-happy and I’ve probably said too much already) except to admit that it was fantastically difficult and left no brainspace for anything else. Save book reviews and a couple Facebook posts, I didn’t write jack shit for a year, unless it was related to pedagogy. I was barely even reading books. If I didn’t plan to assign it or review it, I didn’t bother.

I did not start teaching at my old high school because I loved high school. I wasn’t a happy teenager. But the school wasn’t the source of my unhappiness, just the site. In fact, going to that school probably made things much easier. The school, my teachers, told me that I was talented, that my writing had worth and that by extension, I had worth. Who doesn’t need to hear that?

*

For a long time, I told myself that writer’s block wasn’t a real thing. I really wanted this to be true. My entire sense of self has revolved around being a writer since I was ten. I had to believe I’d never stop.

But I did stop. When your sense of self is shaken, it fucks you up. It also forces you to re-examine the things you insisted were true. One of the things I accepted was that writer’s block is real and that it doesn’t constitute a moral failing.

Writer’s block is another way of saying, I feel fear and shame so great I can’t write without second-guessing my own instincts; it’s way of saying, I’m exhausted; it’s a way of saying, I’m too angry at myself to spend significant time with myself; it’s a way of saying, I need a break.

I’m beginning to think not writing for over a year has been a good thing. I’m not sure, but maybe. After months of internal lesson planning and obsessing over classroom management, I’ve started to think in prose again. I’m thinking about my novel in ways that excite me again. And hey, it may never get published, but I’m also beginning to suspect that’s not really the point. I mean, I really hope it’s not the point.

*

School starts the last week of August. By the time this is published, I’ll be a high school teacher again, a Ms. I’ll talk in my teacher voice, make my teacher faces, feel like I’m drowning in reading responses, and one-to-two page, double-spaced, reflective essays, and five-to-seven page short stories, some of which will be so impressive and exciting that I’ll forget I’m reading someone’s homework.

I’m also going back to the university where I earned my undergraduate degree, this time to get a Master’s in Professional Writing. Basically, my life is an endless feedback loop.

How will I feel, walking back onto those familiar campuses? I know I’ll see ghosts of my old self, my old friends, and want to speak to them. But I’ll also be busy, overwhelmed. How much time will I even have to think? Will any of those thoughts still be in prose?

*

When we write, we go back. I’m not saying we can only write what we know, nor am I saying all writing is (or should be) therapeutic. But you can’t deny writing is an act of memory. At this point in time, memory may be more important to my process than actually producing work. Certainly, not writing is forcing me to reconsider how I define my own worth.

One conclusion I’ve come to: continuous writing does not make me a writer. I know that because I didn’t write for a year and a half, but I didn’t stop being a writer. I know that the way I know my own name.

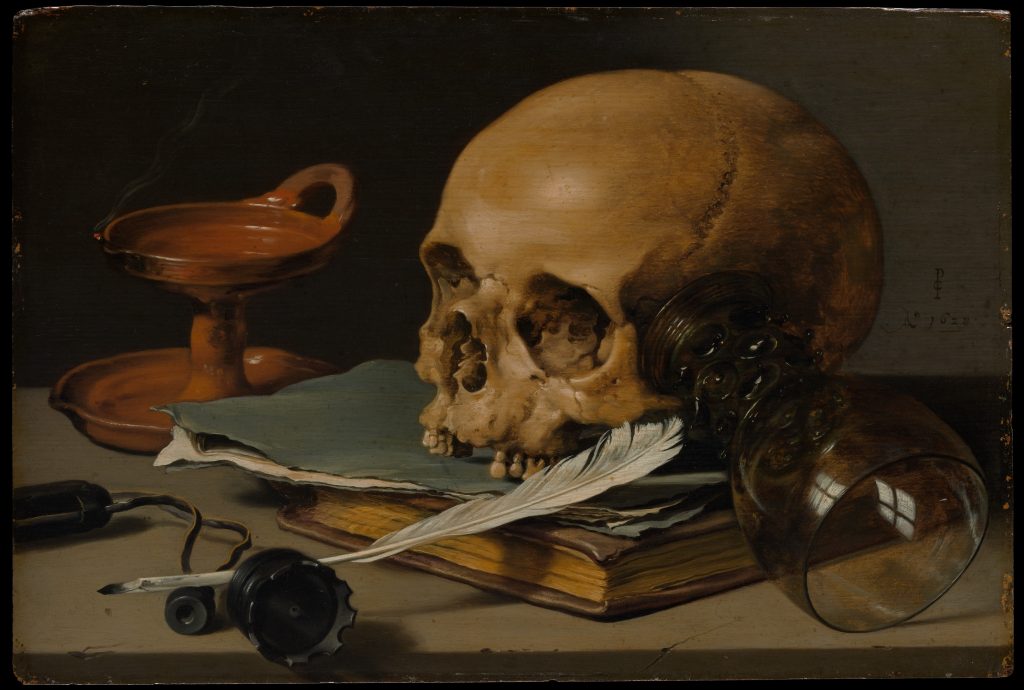

Image: Claesz, Pieter. “Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill.” 1628. Oil on wood. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.