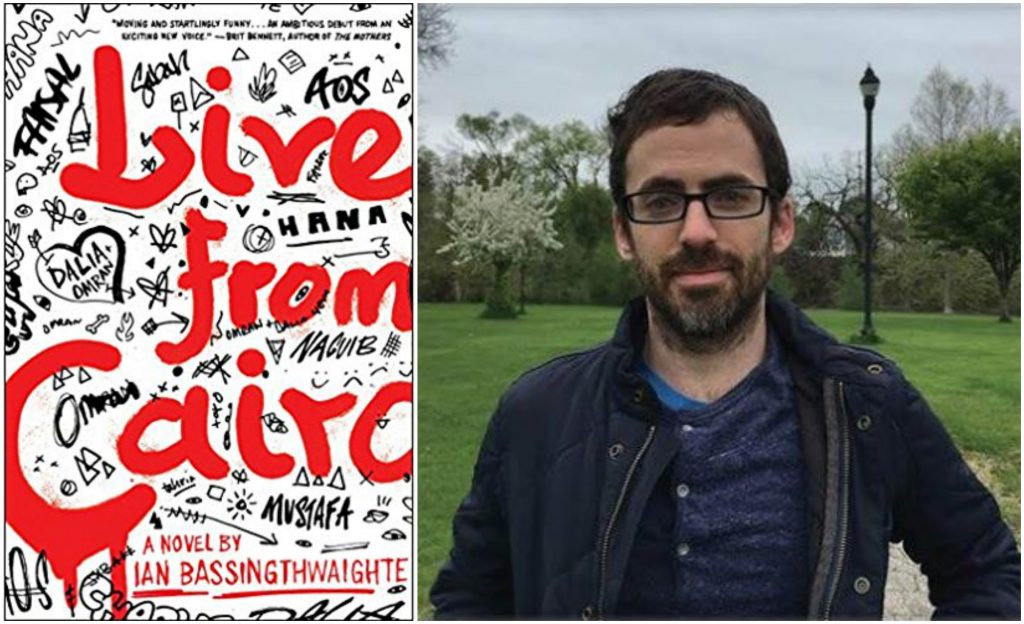

Ian Bassingthwaighte’s stunning debut novel, Live from Cairo (Scribner, July 2017), set during the 2011 Egyptian revolution, follows an unlikely team’s efforts to reunite Dalia, an Iraqi refugee living in Cairo, with her husband Omran, who was resettled to Boston without her. After Dalia’s application for U.S. refugee status is rejected by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, or UNHCR, her American attorney — the bullheaded but compassionate Charlie — devises a plan to bend the law and get his client to the United States.  He recruits his best friend and coworker Aos, an Egyptian translator engaged with the revolution. And, after much persuasion, he convinces the Iraqi-American UNHCR employee who rejected Dalia’s application in the first place to participate in the ploy. Her name is Hana, a new member of the staff, who battles daily with her increasing disillusionment with a job that reduces people to paperwork and harrowing testimonies to checklists.

He recruits his best friend and coworker Aos, an Egyptian translator engaged with the revolution. And, after much persuasion, he convinces the Iraqi-American UNHCR employee who rejected Dalia’s application in the first place to participate in the ploy. Her name is Hana, a new member of the staff, who battles daily with her increasing disillusionment with a job that reduces people to paperwork and harrowing testimonies to checklists.

But the team is not merely battling a broken system, it is posed against time itself. Omran is prepared to return to Cairo to reunite with Dalia, thus relinquishing his asylum status and returning to a city where neither he nor his wife can work or maintain a standard of living. The dilemma is practically O’Henryian. Dalia and Omran’s love is both their solace — this reviewer relished every affable, tender phone call between the two — and their potential undoing. It is, as Charlie muses, not “something they could eat or live inside.”

But the novel is as much about its central couple as it is a searing rumination on the ways in which humanitarian crises reduce their victims to statistics and exceptional anecdotes. It is about bureaucratic futility, friendship, loss, and the complicated line between right and wrong. Brutal, arresting, and heartfelt, Live from Cairo spins out a tale of deft messiness with unflinching prose and a surprising dash of humor.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak to Ian Bassingthwaighte about non-traditional love stories, his work as a multi-genre artist, and how his experience at a legal aid nonprofit in Egypt informed the writing of Live From Cairo.

I suppose we should start with the essential first book interview question: when did you know you had to write this book? Or how did the idea or impetus occur to you?

I went to Egypt on a grant, so was supposed to be writing — or researching, at least — a novel from day one. I was young and passionate, but less than informed; I hardly had a topic, much less a story. Weeks passed. I spent most of my time drinking beer and otherwise being an insufferable twenty-something. Then, serendipity. I found myself, having no legal background whatsoever, interning at a legal aid nonprofit in Cairo, where I conducted intake interviews for primarily Iraqi and Sudanese refugees. This involved compressing myriad, often sprawling tales of woe into five-page testimonies. “On October 3rd, while returning home from the cafe, Mr. X was kidnapped at gun point; he was shot once in the leg. Other injuries sustained during his capture include…” — followed by a list of tortures so creative and severe that it felt cruel to put them in ink. Like writing them down would prevent the client’s memory from fading.

At some point during those months, I found my story. Or I found the problem around which my story was built: a resettlement system so flawed that it ceased to function at the required scale, leaving most refugees to linger indefinitely in camps, slums, tent cities, or impoverished neighborhoods that disappear into the urban sprawl. Those unable to endure the stasis, the boredom, the lack of resources have just one option: to make perilous journeys of their own accord — across seas, across deserts — with the faint hope that their “illegal” migration might end in some kind of recognizable life, should they not perish en route.

I was unprepared for this kind of sorrow. And must admit I thought briefly about leaving. But that sorrow came to have a purpose in my life. It made me angry. Which made me write. Just a story, at first. But one that resisted every attempted ending until it was 336 pages long.

Your novel delves rather specifically and graphically into the violence enacted against the characters attempting to navigate the resettlement process, Dalia and Omran. I found it aligned interestingly with the prominent theme of desensitization. Given your experience of transcribing these testimonies, did the inclusion of these descriptions feel particularly important to you?

It wasn’t until someone else — in this case, my mother — read the book that I realized there was anything graphic about it. I remember her saying something like, “This torture stuff is … not pleasant.” But it was normal. An inescapable part of my clients’ lives; and, as a result, my life. The psychological impact was swift and unsettling. Even in the comparatively short time I spent at the legal aid project, I could feel myself being hollowed out. “You were hit in the face with a tire iron? Okay. Let me write that down. You were electrocuted with a battery? Okay. Let me write that down.”

I don’t want to inflict this kind of second-hand trauma on the reader, but feel its important to convey torture the way victims seem to remember it. It’s more than just a physical injury. It’s a smell. A voice. Usually a man’s voice. It’s a feeling of shame. Of utter powerlessness. It’s wanting to die, but not being able to. It’s a vivid memory that grows wildly over time. It’s the loss of autonomy. It’s a scar that still hurts even years later. To look away from that reality would be to inflict yet another cruelty. It denies the victim a witness.

At its core, Live from Cairo is a love story, maybe even a cluster of love stories — romantic, familial, platonic, etc. But Dalia and Omran have already been together for quite some time when the novel begins, and we don’t learn their “origin story” for quite a while. They’re invested in each other, and the reader is immediately invested in them as well, such that the book explores the lengths both the couple and other parties will go to in order to reunite or preserve that relationship. I feel as though I can name so many novels and stories either about the inception of a romance — two characters falling in love and then having to beat the odds — or otherwise about an already established relationship’s decline, but not all that many about endurance, if you will. What interested you in this sort of a narrative?

I can see why falling into or out of love is so attractive to storytellers; those spaces are, by their nature, dramatic. Whereas a relationship between its inception and death — the period in which those involved are more or less content to be together — is harder to make interesting. Unless, of course, there is an immense external pressure on the relationship. Some mortal threat. At which point the love story becomes a survival story. A figurative matter of life and death. Or literal, as the case may be.

This is not to say that my primary interest here is craft. Or that I was even thinking about craft when I wrote their marriage. I was more interested in giving Omran and Dalia a quiet, perhaps even boring life. What the reader might recognize as “normal.” Two people in a functional marriage. Who plan to have between one and several kids. Who have a cat. And a history. Who will, under the right circumstance, argue. But not degrade each other. The point is to illustrate one of the many unseen costs of war. Refugees were, at one time, just civilians. People with lives. People with families. The theft of that normalcy just tears me up.

Which brings me to the discrepancy between how rich and privileged countries view resettlement and what resettlement actually is. It is not a favor. It is not a generosity. It is not going out of our way to rescue people. It is a moral obligation. An attempt, in some small way, to return what we — the U.S. having a long history of profiting from the conflict business — were party to stealing in the first place: the normal, boring lives of millions of people who just want the right to work, to love, to move, to marry.

It feels reductive sometimes to say that writing generates empathy, and it’s infuriating to consider that this sort of empathy isn’t always reflexive for people. But art is ultimately a point of access as much as it is a point of expression. In addition to being a writer, you’re also a photographer. Has photography affected the ways in which you approach writing, either in terms of subject matter or craft?

In lieu of giving you an answer, I’m going to give you an example. A few weeks ago, I put together a gallery in which my photos of Egypt were captioned with notes about or lines from my novel. (You can view that gallery here.)  One of those photos (below) shows the Saladin Citadel and, below that, a vast sea of apartment buildings capped with myriad satellite dishes. The lines paired with this image come from the first chapter of the book: Hana, standing on her balcony, looks out at the city. It’s the first time she sees Cairo in daylight. She expects to see signs of protest, conflict, battle. But all she sees is a city that’s surprisingly well-connected to space. The odd sight brings about a strange feeling. One that is actually some comfort to Hana. It indicates that she is somewhere new. Somewhere far away from home. The reader will interpret this as they will, but may wonder: what is she running from?

One of those photos (below) shows the Saladin Citadel and, below that, a vast sea of apartment buildings capped with myriad satellite dishes. The lines paired with this image come from the first chapter of the book: Hana, standing on her balcony, looks out at the city. It’s the first time she sees Cairo in daylight. She expects to see signs of protest, conflict, battle. But all she sees is a city that’s surprisingly well-connected to space. The odd sight brings about a strange feeling. One that is actually some comfort to Hana. It indicates that she is somewhere new. Somewhere far away from home. The reader will interpret this as they will, but may wonder: what is she running from?

Here it’s worth mentioning that the best writing advice I ever received came from a photographer. “See what others don’t. Or don’t want to.” This to reveal some heretofore unseen element. Some brightness. Some darkness. Some truth.

Though the book is not told in the first person, you successfully embody the perspectives of various characters in the close third whose backgrounds, viewpoints and personalities are vastly different. Did you find entering into any of these characters’ perspectives surprisingly easy or unexpectedly challenging?

In a 2012 interview with The Atlantic, Junot Diaz, in reference to men writing from a female perspective, said, “The baseline is, you suck.” Privilege gets in the way, like a layer that’s opaque in only one direction. Such that I can’t see women as clearly as they see me. This dynamic extends beyond gender. To race, for example. To religion, sexual orientation, country of origin, country of residence, class, and so on. Any defining characteristic subject to an imbalance of power. Being straight, white, male, solvent, and American means that seeing clearly requires a lot of intentional work.

For that reason, most of the perspectives in Live from Cairo, for the possible exception of Charlie, were hard for me. I had to shed presumptions I didn’t even know I had. Presumptions that resulted in major character flaws. Why in early drafts did Charlie have a rich interior life while Dalia was no more than the sum of her suffering? A victim. A shadow. It took years of fighting and falling in love with her character to make her real. The same was true for Hana, Aos, and Omran. As Diaz notes, this process requires “consciously working against the gravitational pull of the culture.” A culture that demeans women. That dehumanizes Arabs. That demonizes Muslims. That belittles the poor.

Working against this gravitational pull, insofar as writing a novel is concerned, requires seeking out readers who are on the other side of the opaque layer. It requires trusting them when they say your character is poorly drawn or that your portrayal is misogynistic. It requires silencing that part of yourself that would rush to your own defense. “Change it,” I had to tell myself almost every day for the last seven years. Each time with more fear that I would never finish.

You’ve called up two really great pieces of advice/guidelines here, from your photographer friend to Junot Diaz. Were there other writers, artists or works that informed your process of writing and revising Live from Cairo?

There are four authors whose works appear in Live from Cairo: Naguib Mahfouz and Alaa Al-Aswany, two of Egypt’s most regarded novelists; then Jalal al-Din Rumi and Hafez of Shiraz, two of Persia’s most regarded poets. I wouldn’t say they directly informed my process, except that every revision seemed to include at least one additional quote from or reference to these authors. They came along at the right time in my life and will, if for no other reason, stay with me on account of that. I would also credit Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies for inspiring me to write about immigration in the first place. It took such hold of my imagination. It followed me to Egypt. It reminded me why I was there.

Thank you so much for answering these questions. To wrap up, do you see yourself writing about Egypt after this novel?

I won’t say never, but I feel like there are so many contemporary Egyptian authors who are better equipped to write Egypt’s story as it continues to unfold. I was there at a particular time, doing particular work. That’s not carte blanche to write about Egypt in other contexts. Plus, there’s another novel idea that’s been rolling around in my head for a while now. It’s very different than Live from Cairo. Post-apocalyptic, in fact. Though it is, in a way, still about immigration. Who gets to move. Who gets to live.

Find out more about Bassingthwaighte’s work at igbass.com, or follow him on Twitter @iangbass.