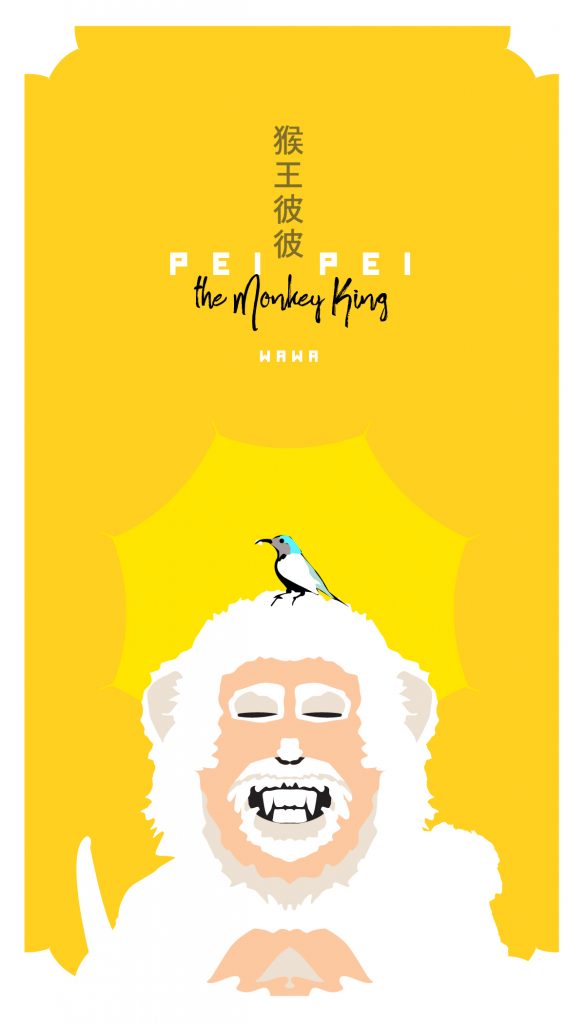

Hong Kong poet Wawa writes from an extraordinary intersection. Her poems in Pei Pei the Monkey King, a book set within a city where enormous shopping malls and historic temples stand one next to the other, where pet birds sing from cages in city parks while Umbrella activists protest for universal suffrage, capture an urgent and tumultuous sense of change in a place hurtling toward its future—specifically, 2047, when Hong Kong will be fully absorbed into mainland China.  And yet, these poems also serve as an astonishing preservation of childhood imagination, delivering raw fables alive with animal immortals and magical forces, in which caterpillars enter our bodies through our navels and flying trees whisk us away on starry evenings.

And yet, these poems also serve as an astonishing preservation of childhood imagination, delivering raw fables alive with animal immortals and magical forces, in which caterpillars enter our bodies through our navels and flying trees whisk us away on starry evenings.

I had the chance to write with Wawa and translator Henry Wei Leung about these poems—published last year in a lithesome volume from Tinfish Press—and the complex terrains they both come from and enter into: from Nietzsche’s horse to political activism to the multiplicities of “Chinese” to what it means to be a “Hong Kong” or, for that matter, “global” poet.

I saw from behind It must have been him

He sat alone on the bluff of a slope

Thundering to the city under the slope

I dared not approach.

Tell me about Pei Pei. Who is he? What is his power? What is his plight? We can certainly see in him the famous monkey king, Sun Wukong, but what about other kings (Hanuman?)? How does he represent or protect Hong Kongers?

Wawa: I hadn’t thought about who Pei Pei was until now. Pei Pei is not Sun Wukong, not any king, and he doesn’t have powers. He actually comes from Nietzsche’s death and the tale around it: the Turin Horse. After all the “Übermensch,” all the “amor fati,” all the “God is dead,” all the Zarathustra leading mankind out of a Godless world, the poor philosopher didn’t become any God. No nirvana, no resurrection, only a total mental collapse after trying to protect a horse from being whipped, with his arms raised, sobbing, until two policemen approached. For two days he lied silent and motionless, and then he uttered his last words, “Mutter, ich bin dumm” (Mother, I am stupid). He remained silent and demented for ten more years before finally dying. Nietzsche, or Zarathustra, did not like men, but he loved mankind. This intense, absurd tragedy, I realize now, is my invisible foundation. The myth of Pei Pei is born here—an image that picks up the devastation between Nietzsche and the world and between me and Hong Kong. The dead part of me still lingers in Hong Kong through Pei Pei.

Catercatpill Catercatpillar

Why won’t you grow up with the little girl?

Could it be you’ll be a butterfly of the sea?

These poems preserve or discover a child’s vision, something you claim even directly in the interview. Tell me about this vision, about fable, and how they work in these poems, especially within the context of political protest.

Wawa: Hong Kong’s children are endangered. Adults don’t give the time and space for them to exist. If I were a place, I’d rather be seen only by children, shooting out all sorts of weird questions every day, than co-exist indifferently and unseen with grownups. Hong Kong is very fast and crowded. Everyone has to see so much and so fast, know so much and so fast, multi-task fast, shuffle everywhere fast. Grown-ups train our kids into fast mini-adults who don’t go to parks, who can’t stop and wonder. In order to see new things and be surprised again, we need to detox, we need to un-know our answers and habits. The emptier the mind is the better, so we can be shocked by a butterfly. But of course, I can’t be a child again and I do know things. So the poems are created out of a paradox of two forces going in opposite directions: this intentional empirical un-knowing, which resembles a kid’s mind; and the unintentional cognitive sediment that I’ve collected and carried with me all along as a political citizen, as a world’s human. In short, I keep un-knowing the world while still knowing it. The poems erupt as an aesthetic exit out of this tension.

Henry: “Protest” is not the right word here, even though my translator’s introduction does frame Hong Kong and the book in terms of the Umbrella protests. But there’s a nuance here that I’ve been hashing out with my poetry students all semester. Protest is reactive and time-sensitive, while poetry aims for the timeless, aims for a form to sustain itself. So the poem as protest is an uninteresting specimen except in documentary cases of extremity. But the poem as witness, or the poem as activism: that’s a different conversation. I mean “activism” in the way that Maria Tymoczko identifies it, as a term emerging after World War II, when dissent was no longer limited by the names of a specific cause—Bolsheviks, Boxers, et al.—but became part of a broader sense of social consciousness in which nobody, especially after the Nuremburg trials, could afford to think any longer that they were not responsible for their society’s atrocious machinations. Perhaps this context can offer us another way to understand the tension between knowings that Wawa describes.

From time to time, flying trees stop by the windows to see the children within. The cages are very small; when I was little I became so big that I could no longer move inside. Then one day I opened the cage, opened my hands, and was picked up by a flying tree, to discover that all the small birds here have grown into bumble-elephants. They jostle out of their cages, then cram into elevators.

What about surrealism? What about the boundaries of thought and language?

Wawa: I grew up in music, so it’s always music that comes first. Then the world is filtered through the music. Then I arrive in a poem, and I start wanting to sing. Then the language starts unfolding images. I have to choose between Chinese and English and it’s my singing instinct that decides which. My conception of surrealism is not very precise. Maybe because I grew up mentally ill, my sense of reality is already very weak.

Henry: I met Wawa while I was in Hong Kong for a research project, originally, to test the Whorf-Sapir hypothesis in literature: essentially that there is no boundary between thought and language, that the limit of your language is the limit of your worldview. Yet here we have a book that tries, in some ways, in two languages, to unlimit a world. Bilingual readers will recognize the inherent shortcomings of the translation: how in Chinese a “flying tree” can grammatically be a name (Flying Tree), an object (a flying tree), a definite object (the flying tree), an object pluralized (the flying trees), a category pluralized (flying trees), and a category idealized (flying tree)—all at once, depending on context, while the English version must limit the material possibilities. This is not even to mention how time operates in a radically different way in each language. All this is the test of a language: not what it can do, but what it must do. This is perhaps a commentary on poetic traditions as well. Consider how Ezra Pound could have so admired his own misunderstanding of the image in the Chinese language, and then appropriated it to introduce more image-things into English-language poetry.

Holy shit! Mr. Satan’s schooling in the school!

One by one I scoop the flowers up

Crawl out on my arms

Both my legs are rubbering!

What about the boundaries of translation? Can you articulate for American readers the set of challenges for the two spheres of translation this project undertakes: first, that of Hong Kong Chinese (Cantonese) to English, and second, that of Hong Kong Chinese (and here also its idioms/dispositions) for mainland Chinese readers.

Henry: The book’s introduction covers a lot of this technical linguistic terrain, and I remember thinking at the time that if the poems were even more intensely Cantonese—as some of Wawa’s more recent work has been—it would be ironic if a Mandarin reader would have to pass through the English translation first in order to understand the tone and context of the Chinese text. (This is taking for granted, of course, my argument in the introduction that the question, “Which Chinese?” has much more profound ramifications than the mere question, “Which dialect?”) But your question raises another oddity: there is almost certainly no mainland Chinese readership for this book. Is an ideological boundary therefore the exact boundary of translation?

Green Balloon singing on the highway

Gently gently hop to the left hop to the right

Hop to the left hop to the right gently gently

Inching from the left lane

Drifting from the right lane

Until a high-speed taxi pops it.

Hong Kong feels so much, in these poems, like its own discrete world. Can you talk about geography and place, and some of the recurring landmarks and themes we see here: Lion Rock, the ferries, the centers of commerce and tourism? What about Hong Kong as Earth?

Wawa: The places in my poems are in Hong Kong without any intention of setting them in Hong Kong. I have no intention to write as a “Hong Kong poet” or make my poems sound indigenously or locally Hong Kong. My relation with the places in the poems is like a kid’s relationship with everything around. Shopping malls, financial districts, ferries, buses; they’re the same in the eyes of a kid because the biggest thing in life is to play and everywhere is a playground. The places in my poems, of course, are representative of Hong Kong; but the kid there is universal. Kids are similar everywhere in the world.

Dong Dong Gramma has forgotten luh

Ah Fook the myna keeps crowing

Revolt! Revolt!

“Dong Dong Gramma and Myna”—I hear so much of the American blues in this poem, and I will use that echo to ask about your broadest influences as a global poet (as noted, you often write in English—this is in fact your first Chinese work)? What else do you read? Listen to? Where might we find some of these influences in the book?

Wawa: “Dong Dong Gramma and Myna” actually comes from a Hong Kong oldie, “Love Without End,” a song from a movie of the same title in the 60s. For years, I was extremely picky about the enunciation of these lines from that song: “don’t know anymore / don’t know anymore.” I wrote short stories in Chinese when I was younger, but yes, this is my first time writing poems in Chinese. It wasn’t planned. I was only hiking on Lion Rock one day and then some kind of sorrow started to gather and then I felt that I needed a song. It’s actually sad to be a “global” poet. It feels homeless to me. I need a lot of music in order to write, like a lot of post-rock/ambient stuff like Hammock and Sigur Rós, Debussy. I also like staring at gestures and images like those in Björk’s music videos. I like to read children’s stories and myths, and the philosophical work of Nietzsche and Taoism. I don’t read a lot because I can’t focus. I can’t read more than five sentences at a time. But I listen to music 24 hours every day.

Henry: The blues runs deep in my linguistic habits, so if you hear it in the poem, it’s the mistake of the translator. A very interesting mistake!

Within ten years

I’ve no less than ten warships full of golden peacocks

And I make my home on the pitch-black sea

Between the globe’s earliest island and latest island.

What about Hong Kong influences? Who else should we be reading from Hong Kong? Where can we go to learn more about Hong Kong’s literary scene?

Wawa: Xixi is good. Cha, too.

I said one need only enter clamor’s depths

Speaking with oneself

To have the quietest conversation.

Finally, what are you working on now?

Wawa: I’m editing a “renga” project which I worked on with my husband while I was away in Vermont last month. We responded to each other’s poems every day during this period of long distance. Me in Chinese, him in English. Next, we’ll translate each other. In Vermont, I liberated impulses that have been repressed for at least a decade: liberating my poems from the page to the realm of the experiential, the spatial, the installation arena, in order to reproduce my experience of poetry. I’m bringing my poems into four art projects now.

My next proper project is a book of prayers/hymns that came to me during my stay in Vermont. They will be prayers for the suffering souls of the people who have lost homes on the land of America, and those who will lose home on the land of Hong Kong. It will take the form of Buddhist sutras, and the way Buddhist scriptures are “read” by chanting. They will be written in Chinese and then Henry will translate them into English. Lines of these prayers will be chiseled on stones collected in the woods here in America and in Hong Kong, then thrown back to where they are found. Hong Kong needs her own prayers and prayer-sayers.

Wawa (also published as Lo Mei Wa) is a Hong Kong poet. She received her degrees in Philosophy in Hong Kong and the Netherlands. She has been a soprano, an indie singer, a lyricist, an art and design magazine editor, a philosophical counseling assistant, and a cowherd in Hong Kong. Some of her work can be found in Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Guernica Daily, The Margins, Hawai’i Review, Apogee Journal, and the anthology Quixotica: Poems East of La Mancha. Her collaborative work with artists has been featured in various art exhibits in Hong Kong and Glasgow. She is the author of Pei Pei the Monkey King (Tinfish Press, 2016). She lives in Honolulu, Hawai’i.

Henry Wei Leung earned his BA from Stanford University and his MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program. He recently dropped out of a PhD program at the University of Hawai’i. He has been the recipient of Kundiman, Soros, and Fulbright Fellowships, among others. He is the translator of Wawa’s Pei Pei the Monkey King (Tinfish, 2016), and the author of a chapbook, Paradise Hunger (Swan Scythe, 2012). His new book, Goddess of Democracy, was selected by Cathy Park Hong for the Omnidawn 1st/2nd Book Contest and is due out in Fall 2017.

Henry Wei Leung earned his BA from Stanford University and his MFA from the Helen Zell Writers’ Program. He recently dropped out of a PhD program at the University of Hawai’i. He has been the recipient of Kundiman, Soros, and Fulbright Fellowships, among others. He is the translator of Wawa’s Pei Pei the Monkey King (Tinfish, 2016), and the author of a chapbook, Paradise Hunger (Swan Scythe, 2012). His new book, Goddess of Democracy, was selected by Cathy Park Hong for the Omnidawn 1st/2nd Book Contest and is due out in Fall 2017.