There’s this particularly troubling meme that has been cropping up on my social media feeds as of late. “In a world full of Kardashians,” it reads, “be Helena Bonham Carter.” I have seen it shared by both one of my former students and one of my former teachers, and the symmetry of that unsettles me. In the accompanying image, the Kardashian sisters are nowhere to be found. (How appropriate, it seems, to render them invisible, to not even invite them to their own denunciation.) Just Helena Bonham Carter is pictured, draped in a cozy sweater and a bohemian skirt, one bra strap exposed, her hair piled on top of her head in a composed messiness. She has a mug in one hand and her other hand is perched on her hip. She stares straight into the camera and — maybe I’m reaching here — even she looks a little skeptical.

There’s this particularly troubling meme that has been cropping up on my social media feeds as of late. “In a world full of Kardashians,” it reads, “be Helena Bonham Carter.” I have seen it shared by both one of my former students and one of my former teachers, and the symmetry of that unsettles me. In the accompanying image, the Kardashian sisters are nowhere to be found. (How appropriate, it seems, to render them invisible, to not even invite them to their own denunciation.) Just Helena Bonham Carter is pictured, draped in a cozy sweater and a bohemian skirt, one bra strap exposed, her hair piled on top of her head in a composed messiness. She has a mug in one hand and her other hand is perched on her hip. She stares straight into the camera and — maybe I’m reaching here — even she looks a little skeptical.

The comparison is ludicrous. It’s a false dichotomy. Helena Bonham Carter is an actress, the Kardashian sisters are models and businesswomen. It’s like saying in a world full of Manning brothers, be Daniel Day Lewis. In a world full of bicycles, be an umbrella.

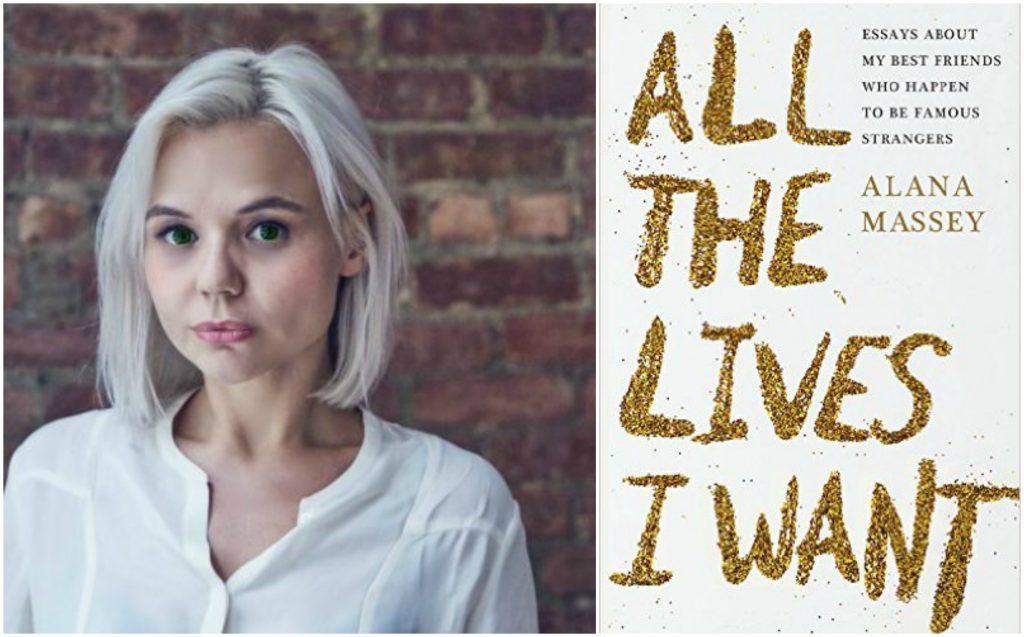

The opening essay of Alana Massey’s debut collection, All The Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to Be Famous Strangers, undoes this notion immediately. In “Being Winona; Freeing Gwyneth: On the Limitations of Our Celebrity ‘Type’,” Massey cautions the reader of the risks of making the female celebrity into a “safe canvas onto which others can project their own desires, including the defiant and childish desire to define oneself as against the things she is alleged to stand for.” Here, she demonstrates that she is not concerned with putting her subjects in competition with each other or to use them as paragons of wrong and right. What follows is a much more sophisticated engagement with the women that people our cultural consciousness, a serious and jocular and tender and sometimes totally crushing discussion of fandom, heartbreak and forgiveness.

It is shocking how refreshing it feels to have women be put in conversation with each other rather than competition, and how the landscape of Massey’s cultural criticism flourishes for it. Here, the stories of Princess Diana and Lisa “Left Eye” Lopes work together to dismantle and reclaim the myth of the crazy ex-girlfriend. Lana del Rey, Fiona Apple, and Dolly Parton encounter, worship, and blaspheme man and God alike. All The Lives I Want manages well to acknowledge of the absurdity of pop culture while still giving its figures the dignity of engagement and criticism.

But perhaps the most poignant connections Massey draws are those she forms between her subjects and herself. Beneath the discussions of Scarlet Johansson’s character in Lost in Translation, manufactured rap beefs, and the disturbing fascination with the Olsen twins’ virginity lie acute and searing observations of the sex industry, and the needless but somehow mandatory emotional labor women put in for mediocre, undeserving men. Here, Massey calls forth her own experiences with sex work, eating disorders and terrible men not so much as confession but as a means of engagement with both her subject and her reader. She becomes the conduit. “I think that ultimately [All The Lives I Want] is not about my experience, I don’t think it’s personal beyond that it happened to me,” Massey told me over the phone. She was, she said, hesitant to call the book confessional, “It’s supposed to be about how I have this inkling that other people feel this way and that I’m okay being the person who says it’s true.”

A friend once told me that people don’t want advice, they want permission. I think that’s what Massey is getting at here. We’re allowed to acknowledge all the disgusting ways society has pigeonholed us and the ways in which we stay in these holes for their relative comfort. To examine the feeling of potent womanhood that at once feels repressive and powerful. The feeling that your body has become public property. “I believe that part of the project is not just that I want you, the reader, to forgive these twenty-five or so women that come up in the book,” Massey remarked near the end of our conversation, “I want you to forgive yourself.”

*

How did you negotiate inserting yourself and your experiences into your criticism?

I feel as if there is such an overemphasis of ego in cultural criticism, in explaining what the stakes are in writing about a piece of pop culture and stating what skin you have in this particular game. I think that I have always resisted the idea of objective cultural criticism in a vacuum. The subject lends itself to drawing connections to yourself — when I look at someone like Britney Spears, it isn’t just at the level of public scrutiny. Maybe I’m overthinking, but there is something to the fact that I’ve been growing up watching how Britney Spears, let’s say, is treated in tandem with how I’m treated. So, it’s at the level of that insidious belief that women are inadequate and one-dimensional. I know I got here by having this experience, and I can’t be the only one. So, I have no problem inserting the personal, though I do try to keep the personal more universal. Not vague, but I try not to get super granular.

I will admit that at first I was a bit surprised to find Sylvia Plath amongst the pop stars and actresses — even Joan Didion feels a bit like a pop culture icon at times. But the more I think about her placement within the titular essay, the more she feels like she belongs. It’s clever, she’s contextualized within the book as the Sylvia Plath. How do you understand her place in the collection?

The book began as something very different. It wasn’t especially pop-focused, it was more of a rereading of the documents about culturally-relevant women. I thought, let’s do some forensics on these histories. Sylvia Plath came up because I hadn’t read her until I was twenty-nine and I knew her as a sort of avatar for a certain kind of girlhood experience that trickles into adulthood.

But I don’t want to say that I’m writing about just Plath the avatar rather than the real person. She’s not someone who has a richly-documented the body of material from her actual life and fame. She was someone whose treatment I got really angry about — a lot of these are in part motivated by anger — in that people dismissed Sylvia Plath or her work because it’s about her. They don’t recognize the sort of creative lack of imagination that could provoke someone to think her writing isn’t worthwhile because it’s personal. I mean, why is anyone particularly interesting? I always say — I’m not much but I’m all I think about.

So if you’re doing it in a way that is impactful to young women, you’ve done a great service. It’s not fair that we sometimes just consider her to be the girl haunting the Internet.

The girl haunting the Internet! It does feel that way sometimes.

I don’t want her to just be the ghost that girls love.

So how do you respond to people who bristle at Sylvia Plath’s placement in this book?

People have said she and Joan Didion don’t belong here because they’re higher brow. If those people don’t think Sylvia Plath and Lil’ Kim are in the same tier of female poets having a particularly feminine experience of negotiating their value in the world, I think that’s a really impoverished view of what art is. I think the people who appreciate Sylvia Plath and the ones who appreciate Lil’ Kim have the same rich interior lives. I don’t think we should separate these things out. Ultimately, it’s about who we attach to and not who we are assigned, who lingers after the fact, who lingers with you.

So who do you hope your book reaches?

That’s a hard one. What I’ve found interesting in reading the reactions to this book so far is that the people who engage with this book are so across-the-board aesthetically. I’ve had many people tell me, “well, obviously, the Britney one is the best one” or “the Amber Rose one is leaps and bounds ahead of the others.” But I think I want this. The process I hope by which people engage with this book is that they come for the Britney, stay for Anjelica Houston and Dolly Parton. I want them to recognize the threads that go through these lives.

I always have this hope that people will come to it and say, “oh, I’m not crazy, oh, that’s why that bothered me.” I hate the word unpacking, because it sounds very grad school seminar. But I hope they can maybe see the reason that this movie bothered them or this book bothered them or this series of headlines in 1999 bothered them may have been this. I hope they can think, “oh, here’s what actually happened.” Our memories are frequently distorted by a dominant narrative.

So you hope to disrupt the narrative?

I want this to be a way of forgiving these women and a way of forgiving ourselves. I shed a lot of tears about a lot of things. “Oh my god, the poor very wealthy!”

But these are important people to acknowledge. It’s important to recognize their full humanity more actively. My goal is for readers to see a thing that happened to them or a way they experienced the same myth that they are inadequate and that they are living a different version of their own life.

I went to divinity school, so I’m very forgiveness-oriented. Everything needs to have a good solid moral core — you walk away healed.

*

All The Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to Be Famous Strangers is out now from Grand Central Publishing. It can be purchased here.