“Larry in Love,” by Jennifer Moses, appeared in the Fall 2013 issue of MQR.

*

Larry moved into Alvin’s old room. Or at least that’s what they told him. “Alvin used to live here! We all just loved Alvin. And now you gots his room.” Like it was a good luck charm, moving into the institutional room in a Baton Rouge hospice where the last resident fairy had died. Its one window looked out onto a scrubby field. Its walls were the color of oatmeal. There was a television propped in the corner. His neighbors played music so loudly he could hear it even in his drugged sleep. Worst of all, he had to share a bathroom, which he wouldn’t have minded so much if the fellow he shared it with, Martin, weren’t such a pig.

Larry wasn’t interested in Alvin—what he was interested in was getting Martin to stop peeing on the floor and throwing his stuff everywhere—but the staff couldn’t shut up about him: “Actually, you remind me of him, a little,” Miss Lilly said one day, blinking to hide her discomfiture. She was the chief administrator, one of those pale blondes with skin so white it looked like you could peel it off, and a face that always looked stricken with confusion, topped by the world’s worst hairdo: a Farrah Fawcett round-the-face arrangement of softly falling waves, thicker on top than on bottom, but hello, hadn’t anyone informed the woman the hairstyle was over before it even began? A part of him wanted to tell her she could do better—a cute short bob, for example. But she had one of those faces that confused him, with small eyes behind glinting glasses, and a vulnerable neck leading to whatever was underneath her clothing, itself a nightmare vision from the depths of J. C. Penney.

“Do I?” he said.

“What I mean is, oh Larry. You don’t have to be so miserable here. There are people to help you. And things to do, if you want to. Alvin lived here six years, and, like you, he’d been a professional man, educated, independent.”

“You mean he was white. A white homo.”

“I didn’t say that. But yes, if you want to put it that way—but what I was trying to say is, he managed to find a way to be happy here, despite his background, his education and so forth.”

“Well, that’s nice.”

“He cooked, is what he did,” Miss Lilly continued, blushing slightly around her hairline, clearly unwilling to step more deeply into the gloom of his lair—the space where, once upon a time, the great Saint Alvin, White Boy Flamer, had lived, dispensing pearls of wisdom and nuggets of love to the ignoramuses with whom he was surrounded.

“He was sort of a mother hen,” Miss Lilly said.

“Do you think you could do anything to get Martin to stop leaving his piss all over the floor and toilet?”

“He’d been in the catering business, before he got sick. He loved food. He’d cook every chance he got, and really, we all just loved him.”

“Because I don’t want to be ugly, but I am goddamn getting goddamned sick of going into the john and there’s Martin’s piss on the floor.”

“Well now. I’ll talk to him.”

“Please.”

~

Martin was a compact, mid-sized man with very small black eyes, skin that looked rough to the touch, hunched shoulders, and close-cropped frizzled hair. His entire body gave off misery, as if he’d been dipped into acid one too many times. He smelled like sour milk. Even his room, which was bare except for the bed linens and furnishings it came with, smelled rancid. Larry could never get over it, the sheer, raw, evil odor of the man, and couldn’t imagine what terrible luck had befallen him, because even the worst addicts and junkies and whores, once they washed up and got dental, managed to look presentable.

“Could you manage to not piss all over the goddamned floor?” Larry said one morning at breakfast as he wheeled himself toward the only empty table. He wouldn’t have said it, either, except on his way to brush his teeth, he’d slipped in the puddle, and it was nothing short of a miracle he hadn’t broken something. Even so, a bruise was rising on his wrist, where he’d caught himself on the way down.

Martin, mid-bite, just looked up at him, his eyes slits of white under heavy eyelids. He looked like he was going to reply, but instead continued shoving his forkful of scrambled eggs into his mouth.

“What your problem, man?” he said. “Man got to make water, he got to make water.”

“That may well be so, but why the goddamn do you have to make water all over the goddamned floor?”

Which was when Annie, who had been taking the breakfast trays out, stepped in. Hands on her hips, she said: “We have rules here, Larry. One of them is we don’t use that kind of language.”

“Yeah,” Martin said.

“So I can’t say goddamn but that animal can piss all over the floor? Don’t you have any rules against that?”

“Why don’t you just settle yoself down now, Mr. Larry, and have yoself some nice breakfast? We talk about it later.”

“Fuck that,” Larry said, and, even though he knew he should eat something—it threw his blood pressure off even more when he didn’t—he wheeled himself back to his room.

~

A day or two later his shirts started disappearing. And it wasn’t as if anyone else in the place had any use for them: certainly not in August, or in the large, extra-long sizes he wore. His shirts were all the same type—heavy, long-sleeved, plaid, flannel button-downs—and the reason was he was always cold. Cold to the point of freezing. Didn’t matter what time of year it was; didn’t matter how high he put the heater up during winter. He couldn’t keep warm. He was like an old lady shivering under her cardigans on the hottest day of summer. He looked like an old lady, too, with what was left of his hair like a dandelion gone to seed, his hunched shoulders and emaciated arms and legs. His penis hadn’t had any interest in anything other than urination for so long he couldn’t even remember the last time he’d had a hard-on, waking or sleeping, but he had no trouble remembering the act of love itself, along with the one man he’d once truly loved, and the others, who, for better and for worse, he’d enjoyed fucking.

Which was another thing: though the rules for residency were strict, and everyone knew them, a new girl, Carmen, moved into the empty room right next to Larry’s and quickly set up shop as a fucking machine. Everyone knew it, and not a goddamned person other than himself had the temerity to complain about it. Of course, most of the other residents were so out of it, so eaten alive by cryptococcosis and CMV retinitis and penicilliosis and God knows what else they wouldn’t notice if an eighteen-wheeler drove onto their beds. Veronica: now, there was a pathetic sight, a massive black woman who talked to herself all day long, infected by her ex-husband, who left her with HIV and two kids to raise. Mr. Richard, Jesus fucking Christ, if he wasn’t a sorry mess, blubbering and blabbering about all his drowned pussy cats and his mother’s knickknacks, boo-hoo, everything washed away in the hurricane. Loretta, who couldn’t remember her brother had died. Still: where the fuck was the night nurse? Because all night, every night, Carmen entertained, and the next day, she’d tell the caregivers she didn’t feel well, she needed to sleep, and could they maybe bring her a cold drink or a cup of tea? He went ahead and told her to quit it but she just gave him one of those looks that suggested his existence was in fact imaginary.

But one night when the noise was driving him stark raving bonkers he hauled himself out of bed and wheeled himself down two corridors to the nursing station, where the night nurse, Linda, was napping. He banged on the door until she woke up and told her he could no longer fucking put up with the fucking: it had to stop now, and he’d call the cops if he had to. She looked at him as if he were an imbecile and said: “I don’t hear nothing.” He wheeled himself back to his room, banged on the wall, and didn’t call the cops.

The woman wasn’t even good looking, and she sure as hell wasn’t young. Big on top and narrow on the bottom, she was built like a swimmer, with oddly endearing hands and feet, as delicate as a dancer’s. Larry suspected she was partly blind—either that or an utter idiot—because she never seemed to recognize anyone at all, including the men she’d been with the night before, all two of them, as the others, including himself, were either wheelchair-bound, incontinent, or unhinged.

“They’re pigs, I tell you,” he told Miss Lilly. “Nothing but pigs. Do you understand? Runting and grunting all night long.”

“I’ll talk to Carmen.”

“You’ll talk to her? She’s turning tricks, I tell you. Nightly. Every goddamned night. And she’s so loud I can’t sleep.”

“Linda hasn’t said anything.”

“Linda is a lazy slut.”

“Let me handle this, would you, Larry?”

“The way you’re handling Martin and his pissing?”

“We’re all just trying to do the best we can.”

“Would it kill you to move me into another room?”

“There are no other rooms, Larry. You know that. We’ve been through that before. And anyway, you have a really good room, right in the corner, and looking out onto the field. Alvin always said it was the quietest room in the entire building.”

“Fuck me,” Larry said.

~

The woman stayed but the fucking stopped, or at least he thought it did: he was so sick, so zonked out on painkillers and blood thinners and heart medication he couldn’t tell. Which was just another of the million ironies that now made up his life. Though he was positive, it was his ticker that was killing him—hereditary heart disease. His HIV, barely visible, was merely the excuse he’d needed to be accepted for full-time residential status.

Every now and again someone would knock and open the door a crack and ask him if he felt like company and he’d tell them not today, no, not today, darling. They knocked again. No, no, go away. Hello. Who knocked? Was it Bunny? Ah, Bunny—his first love, a sweet Mexican who worked mowing lawns in the neighborhood in New Orleans where he’d grown up. Larry was older than Bunny but Bunny was already working full time doing lawn care and couldn’t believe Larry had an entire room to himself, even after Larry had explained he had four sisters who all had to share rooms but because he was the only boy he got his own room, and anyway, it wasn’t really a bedroom at all, but a kind of annex off the playroom his parents had walled off when he was born. The neighborhood wasn’t anything fancy, either: the same three- and four-bedroom one-story brick house with a carport or, if your father was doing well, a detached garage, every single one of them packed with a big Catholic family who sent their kids to either Saint Aloysius or Mercy. And anyway, Bunny was his first, a skinny strong boy with beautiful eyes and hair as thick as carpeting, and of course they’d had to sneak it, managing it quickly, and as often as possible, usually on Sundays when the rest of Larry’s family was at church. Only one day the rest of the family wasn’t at church: only the girls, along with their mother, were. Larry’s father was sleeping one off in the big master bedroom at the other end of the house, the room Larry and his sisters called the Room of Gloom, shadowed, moist, and off limits, filled with oversized walnut furniture and draped in various shades of dark greens and moss browns. That was the day Larry’s father saw something he wasn’t sure he saw, and began to suspect his only son—the tall, strapping, handsome boy who surely was slated for better things than what Larry’s father himself had gotten—liked boys. To make sure it would never happen again, he punched him, hard, in the face.

“Is that you, Bunny?”

“Larry? Are you awake? Do you feel well enough to have a visitor?”

And to think after all that—after he had sidestepped the issue for years, dating girls and even playing football before it was obvious to everyone from the postman to his own pet birds that he was headed down the slippery path to full-fledged faggothood, after his mother’s tears, and his father’s threats, and the trips to the priest, and the trips to the therapist, and then, thank God, his own flight to LSU, and his mother’s subsequent cancer and death, and then each of his sister’s marriages and divorces and marriages and children and boob jobs and face lifts and new cars and trips to the dry-out farm, during which he himself had stayed above the fray, moving first to Los Angeles and then to Cape Cod and finally to Florida, the whole time staying financially independent, not wanting to be a burden to anyone, and now, because he didn’t want to burden his family, he’s here, at a group home for impoverished patients in goddamned backwater Baton Rouge, instead of somewhere else where they’d have to either pay or look after him themselves—and to think even now not one of his sisters had bothered to so much as call him on the phone, and the one sister who had gotten in touch with him had done so by mail, sending him a birthday card that read: “At Our Age, Let’s Forgive and Forget,” and under that, her own uptight control-freak sorry-ass scrawl: “Maybe it’s time you can tell me you’re sorry.” Cunt.

“Bunny?”

“No, Mr. Larry. It’s me. Suzette.”

He opened his eyes. She was sitting in the shadows opposite the bed.

“Who?”

“Suzette. I volunteer here.”

Then he remembered: Suzette. She took him out driving sometimes. She wore her hair in a too-tight braid.

“You want me to go away?”

“Have you seen Bunny?”

“Who’s Bunny?”

Some of the other residents didn’t like her—they said she was stuck-up—but he didn’t mind Suzette. At least she wasn’t stupid. Nor did she seem to give a rat’s ass about Jesus. She just seemed to him to be—well, he wasn’t sure.

“Larry?”

“What?”

“Who’s Bunny? You keep asking if Bunny is here.”

He was fully awake now, and, as far as he could tell, neither nauseated nor in pain. Mainly he was dopey, drowsy, but that was fine with him. He also had to use the bathroom, but the need wasn’t urgent.

“My first boyfriend,” he said.

“Tell me about him.”

“He was gorgeous.” He closed his eyes again. “He had the most beautiful, rounded arms.”

“When was the last time you saw him?”

“Oh honey, if I could tell you that—” He drifted off again, then woke with a small jolt.

“I was all of seventeen,” he said. “In Catholic New Orleans. You can only imagine.”

“I can’t, actually.”

“We were both so young. We didn’t even talk. Didn’t have to. But there was no ugliness to it, either. It was just all so, well, natural. He was a force of nature. We both were.”

“Young love,” Suzette said.

It was funny, too, because in truth he hadn’t given Bunny much thought at all, not all these years, not even when he moved back to Louisiana so he could get his benefits, so he could be closer to his sisters, even though all four of them turned out to be nothing but judgmental selfish cunts. Couldn’t even be bothered to phone him, not even on Christmas, or his birthday, or the day he’d moved in, or the day he got out of the hospital for the seventh or eighth time, this time after a coronary bypass.

“How about you?” he said. “Any steamy lovers from your past?”

Astonishingly, she froze.

“What’d I say?” he said.

“I’d really rather not talk about it.”

“Well,” he said. “Don’t get your titties all in a twist.”

~

It never ceased to amaze him when grown women, women with husbands and children, acted like they were vestal virgins. His own sisters pulled that one on him all the time, or at least they had when they were still actually treating him like a human being, before he’d had to sell his house and business in Cape Cod and move in with friends. His oldest sister, Barb, had lectured him about his language when he’d dared to suggest her pants were so tight you could see her pubes. As if she didn’t have such a thing. But that was when they still allowed him in their homes, back when he still made an effort to keep up relations with the relations. They hadn’t minded him so much when he was the sibling who’d moved north—you know, the one who was always so different—the one who’d made a nice little living for himself with his upscale wine store. On occasion they even trotted him out: the brother who knows everything there is to know about Zinfandel. But that was years ago, when he still looked like a million bucks, and when Southern women of a certain age and class were beginning to realize having a gay friend or two gave them a certain frisson of stylish daring-do.

And then Miss Lilly, who really ought to have known a thing or two by now, went all virginal on him when, in the course of a normal conversation, he’d said: “Once you’re a bottom you’re always a bottom,” and then she went all pink on him before she finally said: “I guess I always assumed y’all took turns,” and he answered, “Oh honey, what planet do you live on?”

But with Bunny—well, both of them were each other’s first lovers. They’d been so entranced, neither one of them had stopped to think about roles, or routines, or even, for that matter, closing the curtains. Not that Larry hadn’t dabbled around before, sneaking kisses behind the library, or feeling some boy’s crotch in the bathroom, his hand on denim while his entire being exploded with excitement.

~

He felt better. It happened that way—two or three or four days, sometimes a full week, he’d be plagued by sheer pain, sometimes accompanied by fever, and then he’d be okay again. He’d lost weight though: he could tell as soon as he sat up. His bladder was full.

But no sooner had he wheeled himself into the bathroom, he saw it. This time the beast hadn’t just sprinkled the floor, but had, apparently, sprayed the walls as well. And the stink! Did the man ever bother to shower or use deodorant? He was in no shape to deal with this.

In the hall, he noticed the all-night entertainer’s room was empty—not a sign of her. Actually, the room was better than empty: there was a small, electric candle burning on the dresser, which could only mean one thing: Carmen had died, praise the Lord. Turning back into the hall, he almost ran into Annie, who was carrying a load of fresh sheets towards Veronica’s room. “Feeling better, now?” she said in her usual broadly bovine way, like she’s mooing with pleasure from the feel of sun on her back. “Y’all sure are looking better, that’s for sure!”

“Did she die?” he said, nodding towards Carmen’s room.

“She passed, yes indeed. Gone to the arms of Jesus.”

The question was: where the fuck was Miss Lilly when you needed her? Because he’d be damned if he was going to put up with Martin’s piss-poor pissing habits one more day. She wasn’t in her office; she wasn’t in the nurse’s station; she wasn’t in the kitchen; and she wasn’t in the laundry. Nor was she outside.

“If you’s looking for Miss Lilly, she ain’t here,” is what the cleaning woman finally told him.

“Where is she?”

“Vacation. Back next week.”

“Vacation? What day is it?”

“It Monday.”

That’s when it happened. The door to the smoking lounge opened, and in walked Martin. As usual, he moved slowly, his head down like a bull’s, his skin, dark and rough, as dark as a bull’s, too. Even from across the room Larry could smell his stink, of unwashed privates and unwashed pits and decaying gums and endless cigarettes. But what really got his goat was that Martin was wearing one of Larry’s shirts. It fell off his shoulders, but he’d taken care of the too-long sleeves by cutting them off just below the arm pits.

“Well, for Christ’s sake, if it isn’t Mr. Charming,” Larry said as Martin shuffled wordlessly past him. “And he’s wearing my shirt, too.”

“Ain’t,” Martin said.

“Jesus Christ, you pathetic lying lump of mold. How many more of my clothes have you stolen while I was too sick to notice?”

“Who you calling liar?”

“You, stupid. Because you are. You’re also a thief.”

“Yeah, well you—you a pervert.”

Really—it was all so funny, particularly now that a little crowd had gathered, Annie with a stern expression on her wide face, and Mr. Richard looking sweet in his own souped-up wheelchair, and, from around the other corner, someone new whom he’d never seen before, a white girl who had the same shuffly, down-and-out look as all the others.

He laughed. He laughed and laughed, and only stopped laughing when another nurse, this one named Dianne, approached him and wheeled him back to his room.

“You got to cut all this business out,” she said.

“But the man stole from me. Don’t you understand that?”

“You got proof?”

“I’ll get it. Let’s just look in his room. I’ll bet you my pecker my shirts are in there, somewhere.”

“Never you mind with that. We don’t go snooping like that, not around here.”

“Jesus fucking Christ on the Cross.”

“And don’t go disrespecting me, neither.”

She left. He sat there fuming. He wheeled himself into Martin’s room and found his shirts—what was left of them, anyway, after Martin had butchered them—balled up in the corner. He took every single one of them, rolled back into the nurses’ station, and, throwing them on Dianne’s desk, said: “Exhibit A. And please, if you will, note the odor.”

~

That night, he had a dream. He dreamed he was lying in Bunny’s arms, and Bunny was lying in his arms. It was so vivid he swore he could feel Bunny’s breath on his neck. Then he heard something and woke. In the darkness there was a presence by the bed. He knew it wasn’t Bunny—he wasn’t that far gone—but he also knew it was someone, because the presence had a distinct, moist, unpleasant odor.

“Well one thing I know for sure is that you sure as hell aren’t the ghost of Saint Alvin,” he said.

“You gonna get me kicked out of here?”

“What?”

“I ain’t got no clothes is the thing.”

“They have an entire closet full of donated clothes here. All you had to do was ask.”

“I ain’t knowing nothing ’bout that.”

“Well, it’s true.”

“Shit.”

“Can you leave now?”

“You going to get me thrown out this place?”

“What?”

“They talking about throwing me out. I heard them nurses on the phone, yesterday, talking about it. Talking how when Miss Lilly get back from vacation my ass gon be thrown on out of here. Sent to some state nursing home.”

“Maybe you shouldn’t steal my shirts and piss all over the wall.”

“I got me a problem,” Martin said. “Ain’t you never heard of problems?”

“Me? No, never. I live in the garden of fucking Eden.”

“Where that at?” Martin said.

“The Garden of Eden? The Bible? Adam and Eve?”

“Oh,” Martin said. “Now I with you.”

“Well, thank God for that.”

The man actually squeezed his hand.

“Oh, go away, can’t you?”

Martin didn’t move, but when, a week or so later, Annie came into Larry’s room to inform him Martin had died, Larry didn’t feel much of anything one way or another. “It was peaceful,” she said. “He passed in his sleep.”

“We should all be so lucky,” Larry said.

*

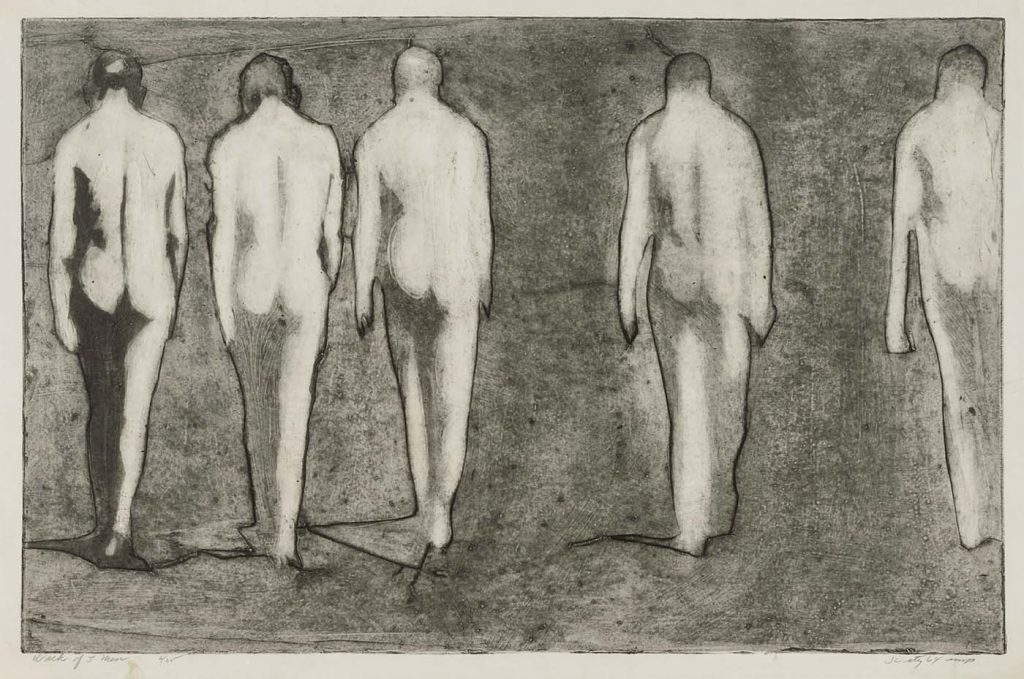

Image: Steg, J.L. “Walk of Five Men.” 1964. Intaglio engraving. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.