“A Meeting in Antibes,” by Karen M. Radell, appeared in the Spring 1999 issue of MQR.

*

The moment I stepped from the elevator I saw him. He was taller than the door to his apartment, which stood open behind him, and his hair, pure white and extremely fine, seemed to float around his head like a nimbus. It was the effect of the late afternoon sun coming from his balcony at an angle and striking him momentarily. There were only a few yards between us and as I approached him, a little awed, for he seemed unreal and not at all like the old photo on the dust jackets of his books, Graham Greene stepped forward and shook my hand.

“Welcome. I am pleased to meet you.”

“I am very pleased to be here,” I said with a genuine thrill, followed by a pang of dismay as I realized my voice had broken like a schoolgirl’s on the word pleased. I had the realization that standing in the same room with Graham Greene I would probably never be more than that—an anxious schoolgirl—though in truth I was writing a doctoral thesis on Greene and Ford Madox Ford. I noticed, in an unscholarly way, that his eyes were a startling shade of blue.

He ushered me into a moderately sized, airy living room lined with bookshelves on one side, a room that opened onto a large balcony overlooking the harbor of Antibes. Rays of late afternoon sun touched everything. A large oil painting, which I correctly took to be the work of a Haitian artist, dominated the wall that faced the balcony. In one corner stood a small trolley with various bottles, glasses, a bowl of limes, and a bucket of ice. When Greene gestured toward it, I felt much less of an intruder.

“Now that you are here, we can have a drink,” he said.

“I think I need one,” I blurted out. “I’ve been very nervous all day about coming over here.”

Greene apologized for having been tied up most of the day (he had originally suggested I come by around ten in the morning); I apologized for having been so nervous; the ice was being broken, slowly. While he mixed the drinks I thought that it had not, after all, been a mistake to come here, that he wasn’t going to let me make a fool of myself. Still, I was glad I had stayed up late the night before in my room at the Royale, listening to the waves and writing down all my questions. I had just spent several hours wandering the picturesque streets of Antibes, too anxious to eat anything, wondering what had possessed me to try to interview Graham Greene. True, his last letter had said, “I will be glad [emphasis mine] to see you on the 26th or 27th of January…” but standing on a parapet overlooking the sea it had occurred to me that such a phrase could signify nothing more than good manners. Taking the drink from Greene’s hand, I was glad I had persisted.

We sat down then and he began to ask me about my thesis and what it was I liked about Ford. He was curious and pleased at my interest in Ford’s work. He said he had met him only once, very briefly, when he, Greene, was still a young writer, and that Ford had been very kind to him. I began to relax and to settle into my task. I was writing everything down, his answers to my questions as well as general comments. I asked him if he minded my doing this and he said no.

Just as it seemed we had started in earnest, his phone in the kitchen began to ring. It kept ringing. It rang at least three or four times in the next ten minutes. He spoke to his callers in English, so it was impossible not to eavesdrop.

“No, they haven’t done anything yet.”

“They’d like to shoot me, I know.”

“No, I’m all right. They’d like to kill me but I’m too well-known.”

“No, no. I’m fine. They don’t dare do anything.”

After all these interruptions, Greene sat down again on the sofa and said he felt he should explain what was going on. The “they” he referred to were the local mafia, sometimes called the Nice or Corsican Mafia, who, as he informed me, controlled not only all the gambling on the Côte d’Azur but also the police and the courts. Greene had just crossed them publicly in a case involving the divorced daughter of a woman he had known for many years and who, as he put it, had once been his mistress. The divorced gangster husband of the woman’s daughter had abducted their oldest child by force, assaulting the maternal grandfather in the process; then the Mafia-controlled courts in Nice had actually granted this gangster permission to keep the kidnapped child, even though the original divorce agreement had assigned custody of the two children to their mother. Greene, normally shunning publicity (and interviews, a fact I was acutely conscious of), had decided to make his outrage very public in order to try to shame the system and to help the child’s mother fight this injustice. He had called the London Times to make a statement, he said, and they had sent two reporters to talk to him that day. He had been with them that morning, because he wanted his position in all of this to be known in England.

The story had already appeared in the French papers because Greene had even tried, in disgust, to return his Legion of Honor medal. The ex-son-in-law complained to the newspapers that Greene had only interfered because his ex-wife’s mother was the famous author’s mistress.  Greene informed me that his answer to this was “Monsieur D—– flatters me. After all, I am seventy-nine years old.” He then smiled, rather pleased with his own wit. He said that unfortunately the French government had returned his medal to him with a letter stating that only death or disgrace can nullify France’s highest honor. It was a fascinating story, being told by one of the best story-tellers in the world. I felt privileged to hear it firsthand. The spell Greene had cast over me was broken, however, by the loud, buzzing sound of the doorbell. Silence. A heavy hand pushed the doorbell again. I expected Greene to get up and answer the door but he didn’t. He sat quietly as if lost in his own thoughts, then looked at me.

Greene informed me that his answer to this was “Monsieur D—– flatters me. After all, I am seventy-nine years old.” He then smiled, rather pleased with his own wit. He said that unfortunately the French government had returned his medal to him with a letter stating that only death or disgrace can nullify France’s highest honor. It was a fascinating story, being told by one of the best story-tellers in the world. I felt privileged to hear it firsthand. The spell Greene had cast over me was broken, however, by the loud, buzzing sound of the doorbell. Silence. A heavy hand pushed the doorbell again. I expected Greene to get up and answer the door but he didn’t. He sat quietly as if lost in his own thoughts, then looked at me.

“I am not expecting anyone else. You are the only person I am expecting this afternoon.” Again, the bell sounded. Greene made no move but looked at me again. With sudden clarity, I understood his reluctance to answer the door: in European apartment buildings, one cannot enter the building itself without first speaking through an intercom to the apartment dweller and then having this same person electronically open the door from above. No one had called Greene on the intercom and now someone was at the door of his apartment. I wondered if I should get up and answer the door for him—he so clearly did not wish to himself. Time seemed to pass very slowly. I did not get up.

There was one last buzz, then Greene pulled himself reluctantly up off the sofa. As I watched him cross the living room, the part of my mind still working in slow motion pictured the door opening, the gunmen entering and shooting Greene (professionals, with silencers), then noticing me and shooting me too, with some surprise but with no regret. I thought of the headlines the next day: STRANGE WOMAN MURDERED WITH FAMOUS AUTHOR IN RIVIERA APARTMENT…. I supposed the police would find my notes. The English Department at Kent State would be angry that I had wasted the four hundred dollars they had contributed to the trip.

Without turning around in my chair, I heard Greene speaking French to someone at the door, someone who responded in a cheerful tone. My life had been spared. When Greene took his place again on the sofa, he explained that it had been the concierge about some repairs. We both laughed with nervous relief and Greene and I were suddenly aware that we had been wrestling with exactly the same fear. We didn’t have to name it.

“At my age, though, one wouldn’t mind dying,” he said, finally. I had no reply for this so I just looked at him. I was too ashamed to tell him I had contemplated going over the balcony.

“I suppose, when one is young, of course, one would mind dying?”

“Yes, I would mind very much,” I answered, with a smile.

Nothing could have broken the ice faster or, I felt, with more certainty. Greene’s Mafia story was more than just a story now; I had even become a small part of it. We continued our discussion for at least another hour and a half—questions and answers—about the expected: his work, Conrad, James, Ford, journalists, Catholicism, the Pope; and about the unexpected: his trip to Northern Ireland, graduate school, movies.

I had my notebook out the entire time. I said I hoped he did not mind my writing down everything; he said he did not expect me to do otherwise. He asked me to tell him exactly what the topic of my thesis was and I told him, a little hesitantly, not sure of his reaction, that I intended to compare his work with Ford’s and discuss both of them as “spiritual heirs” of Henry James.

“What do you mean by spiritual?” he asked.

“I would define spiritual as not being confined to religious matters but rather to be taken in the broader sense of morality and the question of evil in the world.”

“In that case, I don’t object to the term spiritual heirs.” My relief was great, but when we began to discuss The Good Soldier and The Heart of the Matter, we also began to disagree. I was naturally reluctant to cross him in the matter of his own work, but he was so amiable and polite that I actually felt very much at ease when I declared that for most readers Scobie is a hero—for in spite of all his sins he is still the most attractive character in the novel. Greene nodded and lifted his hands, palms up.

“One gets rusty. But it’s odd that people are so attracted to his goodness. Readers aren’t often attracted to the good or the virtuous, or rather, it’s so difficult to make the good characters interesting. They tend to be minor characters.”

According to Greene, one “bad effect” of The Heart of the Matter is that he started hearing from priests, asking for help or advice (as Father Rank does with Scobie). He said it was still going on and he wasn’t happy about it.

“It gets to be too much. After all, I’m supposed to go to them, they aren’t supposed to come to me.”

When I said that I considered this novel one of his best, he merely shrugged and replied that he considered it one of his “chief failures.” He said that Scobie makes too big a thing out of damning himself, that overall, Scobie’s Catholicism is “too exaggerated.”

“The Heart of the Matter is like a Protestant novel. It’s too Protestant; it’s like Catholicism seen from a Protestant’s point of view.”

He disagreed with me again when I said that I felt there was a great emotional and moral decay at the center of both The Good Soldier and The Heart of the Matter—eating at the lives of the characters.

“I m afraid I don’t see this in my novel.” I changed the topic to Captain Ashburnham in The Good Soldier. I said I couldn’t understand why so much of the criticism of Ford’s novel talked about Ashburnham in such exalted terms. I found it hard to respect a man who behaves like an ass most of the time.

“I mean, look at his taste in women … he thinks he’s in love with that courtesan, la Dolciquita,” I said, making a face. I ventured something close to a smirk. And, to my relief, Greene nodded slowly in agreement.

“Well, yes,” he drawled, stretching the two words. “I never met an English gentleman like Captain Ashburnham. The characterization of Ashburnham verges on the unreal at times.” In general, though, Greene was full of praise for Ford and his work. When I asked him what he thought of Ford’s technique with regard to the use of time in The Good Soldier, Greene’s comment was:

“It is questionable, to me, whether Ford borrowed from Conrad or whether Conrad learned from Ford. I have my doubts.” Greene was quiet for a moment before he went on to talk about his own “Ford novel” (his exact words). “The Confidential Agent reads like it was ghosted by Ford.” I had no reply for this as it was, to me, a comparison out of the blue. But when I returned to school, I read the novel again with this in mind and discovered that Greene was right in one respect at least. The Confidential Agent certainly has the atmosphere, the moral climate, if you will, of a Ford novel, but it was several years before I could pinpoint the thematic coincidence between this story of Greene’s and Ford’s The Good Soldier.

I asked about the influence of Conrad on A Burnt-Out Case, but with something of a disclaimer. I told him one of my professors (the department chair) had suggested that A Burnt-Out Case owes quite a bit to Conrad’s Victory, not Heart of Darkness, as some have argued, with the point of similarity that the hero is not able to escape the world—the world comes to Querry after all.

“Would you say this was true?” I asked.

“There are no elements of Heart of Darkness in A Burnt-Out Case. I made the mistake of saying that I took Heart of Darkness with me to read when I went down the Congo. That’s where critics picked up this notion. There is no connection with Victory either. The two protagonists were trying to escape the world for completely different reasons.”

When I asked Greene if there were any contemporary novelists he liked to read, he could name only three: Brian Moore, John Le Carré, and R. K. Narayan. In recent years, I had become a fan of John Fowles. I threw his name out, telling Greene how much I had enjoyed The French Lieutenant’s Woman and Daniel Martin, but Greene shook his head, saying: “I tried to read The French Lieutenant’s Woman, but I couldn’t because I found it so boring. I don’t know what else to say.”

Many of the stones Greene dropped into my deep well, filled half with ignorance, half with longing, did not find the bottom and reverberate until many years later. Looking over my notes after some ten years, I found I had recorded many of his pithy remarks verbatim:

“Lord Jim is a silly book. It reads like a story in Boy’s Own.”

“James is the Master although he did go through a boring period. Wings of the Dove used to be my favorite, but now it’s The Golden Bowl. And I have rediscovered The Ambassadors.”

“For Whom the Bell Tolls is rubbish. The girl in the story would never fall in love with a foreigner. She’d fall in love with a Spaniard. It’s so silly.”

“I met Ernest Hemingway once, in Havana. He found out we were filming Our Man in Havana and came on the set. We greeted each other with mutual distaste.” (Here a look on his face as though he had eaten something bitter.) “We did not shake hands. I’ve always felt there was something unnatural about his macho obsession—it’s not a natural cultural disease for an Anglo-Saxon like it is for Latins.”

“F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote one book (The Great Gatsby) that outshines anything Hemingway wrote.”

“I introduced Evelyn Waugh to Ford and I have regretted it. Waugh wrote a bad war trilogy—not one of his better efforts—and I’m afraid he was inspired by Ford.”

“I have a great respect for Joyce but I can no longer read Ulysses. I get bored by it. The Dead and Portrait of an Artist are my favorites.”

“I like Jean Rhys. The Wide Sargasso Sea is a better book than Jane Eyre.”

“I knew Violet Hunt when she was an old lady—believe me, she was a real witch.”

“Ford suffered from fragments of his lost Catholicism, which crops up in his novels.”

“I do not approve of Edmund Wilson’s complicated criticism of Portrait of a Lady. He tries to complicate what James is doing, which is simple and straightforward.”

“I prefer Brian Moore to Norman Mailer. Mailer is more interested in publicizing himself than in writing. I didn’t like The Naked and the Dead—it’s soft porn. But I did like The Armies of the Night. It might be the best thing he’s done.”

“I knew Diem and Ho Chi Minh. Diem was a little crazy.” (Greene pauses to make a face with mad, bulging eyes.) “Ho Chi Minh was a very elegant man.”

“I have mixed feelings about the present Pope (John Paul II). He’s very liberal on political issues but so conservative on social issues. But I do agree with him on maintaining the celibacy of the priesthood. I couldn’t do it myself, but it’s one of the things I admire about priests. They have to have something, some sacrifice to set them apart from ordinary men.”

“I don’t believe there is any such thing as a bad Catholic or a lapsed Catholic. These are meaningless terms.”

“A few years ago, the English government asked me, quite off the record, to visit Northern Ireland and to submit a report on my impressions of the Catholic parts of Belfast. I suppose they asked me because I’m a Catholic and I’ve done intelligence work before. I was given a driver and an unmarked car; no one knew I was there.” (Greene shakes his head at the memory.) “It was a frightening experience. My driver kept refusing to go to the end of the streets. He was trembling. He pointed out there wasn’t enough room to turn the car around. We’d be trapped, he said. I was more frightened in those streets than I was during the war, when the bombs were falling every night on London. I’m afraid I didn’t have much of a report to submit.”

“I prefer Trollope to Dickens.”

The interview ended when he had to get ready to meet some people for dinner. I felt he had been quite generous and was prepared to thank him for his time and to say good-bye when he suggested I come back in the morning. I was so taken aback that I said something like “I think I could be free in the morning,” as though I had come to France for any other purpose but to talk to him!

In the morning I returned, happily, with the books I had forgotten to ask him to sign the day before. Greene signed them graciously, inscribing one with the date of my visit. He then apologized for having been so preoccupied yesterday that he had forgotten to ask me if I would be free for lunch today; I accepted his invitation with what I hoped gave at least the appearance of equanimity. He excused himself, went to the phone and made a short call. I heard him tell someone in French that today there would be three at his table instead of the usual two. Then we talked about things at random. I never even took my notepad out of my briefcase.

Greene started pulling books off the shelves, asking if I had read them. He also showed me a document once circulated by the late Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier which declared Greene to be, among other things, a drug addict, a Negrophobe, and an enemy of Haiti.

“I don’t know what he means by Negrophobe, actually, but I felt it was an honor to be declared an official enemy of Duvalier. It gave me some idea of what those people felt who discovered their names on Nixon’s list of enemies. I was proud.” This was Duvalier’s response to Greene’s 1965 novel, The Comedians. Greene also told me, with delight, that his friends in the diplomatic service had shown him letters Duvalier had written to other heads of government asking them to deny Greene a visa to their country.

“Did that ever happen? Were you ever denied a visa?”

“No, I wasn’t. But the one country that gave me trouble was yours. Not when Kennedy was president, of course. Then I was welcome. But afterwards, the State Department made things difficult for me.”

“Difficult in what way?”

“Oh, well, they would only issue me a visa for a specific number of days. And even then I had to give the name of my hotel and the names of people I would be visiting. It was very tedious and I always had the feeling I was being watched.” Greene paused at this point, then laughed.

“But I turned the tables on them when I entered the country on a false Panamanian passport and was a guest at the White House for the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty. I was ostensibly a member of the Panamanian delegation. You know, I was good friends with Omar Torrijos; I’m writing a book about him.”

I then told him The Comedians was one of my favorites; he replied he much preferred The Honorary Consul. I believe his exact words were: “I’m rather fond of The Honorary Consul.” This was the strongest term I heard him use for any of his work.

Greene also showed me reports and memos about himself that he had received from the C.I.A. under the Freedom of Information Act. Everything but the subject titles is heavily blacked out. There is nothing to read.

“So much for freedom of information,” he exclaimed.

We were joined shortly by Greene’s friend, the mother of the young woman he had done battle for against the corrupt Nice courts, and we all had a drink before lunch. She drove the three of us and her English-Italian spaniel to the Auberge Provence, where Greene lunched every day and where the owner respected his privacy. An old Frenchman, a mussel seller with a stall just outside the restaurant, pulled a tattered paperback copy of The Quiet American (in French) out of his apron and asked Greene to sign it. Greene asked him what he would like him to write. A grin cracked his old, weather-beaten face as the man answered simply: “pour lui.” Just after we were seated, Greene turned to his companion and remarked:

“I feel bad because I see that man every day but I never buy anything from him.”

“But you don’t eat mussels. You don’t like them,” she reminded him.

Inside, the waiters were lined up to greet us as we came through the door.

“Bonjour, Monsieur Greene!”

“Enchanté, madame,” to me, as each one shook my hand. I felt the dizziness of instant celebrity as all eyes in the place turned toward us with respect. We were shown to a private table near the back window, close to the dessert display, and as we passed the long line of delicious-looking pastries and tortes, Greene turned to me with a knowing look and said:

“They do a wonderful tart here.” (And indeed we did spend some time circling this island of baked delights, after we had consumed the main course, speculating on the attributes of each before finally choosing a simple berry tart.)

Lunch itself is another story. We were, after all, in France and the French never hurry a meal. But it is a story that must wait. When I received an early morning phone call on Wednesday, April 3, 1991, from my best friend (and graduate school roommate) with the news of Greene’s death, it was that first meeting I recalled immediately. Oddly enough, I remembered how he told me he would never kill a spider in any of his houses, even if one had spun its web on the furniture, and how I had lied and said I didn’t kill spiders either, to impress him. I remembered telling him the story of Charlotte’s Web and later sending him a copy of the book, as he had never read it.

I remembered clearly the whiteness of his hair, the color of his eyes, the teal sweater he wore, the sun on the polished floor of his living room, the small, manual typewriter, on which he typed all his own correspondence (my own letters too, I assumed), parked at the end of the table. I remembered his generosity—how he had even laughed at one of my jokes about academia. (I told him I was going to publish an essay titled “The Significance of the Pye-Dog in Modern Literature” in which I demonstrated the insignificance of novels like To the Lighthouse, Portrait of a Lady, and Lord Jim because they failed to include a pye/pariah dog, the symbol of moral and physical decay in Western civilization. Greene laughed quite heartily, so I knew it was not mere courtesy.)

I know he was very old (eighty-six) when he died and had lived a full and successful life. Still, I was very sad when I got the news. A door closed for me with Greene’s death, a door that had opened when I first read The Heart of the Matter, at age fifteen, encouraged by my oldest sister. (Scobie the Just!) Greene himself once wrote that it is the books of our childhood and adolescence that shape our lives most powerfully, most irrevocably, not those of our later years. My life was certainly changed, irrevocably, by reading The Heart of the Matter more than thirty years ago, and I feel deeply the absence of Graham Greene from the literary scene.

*

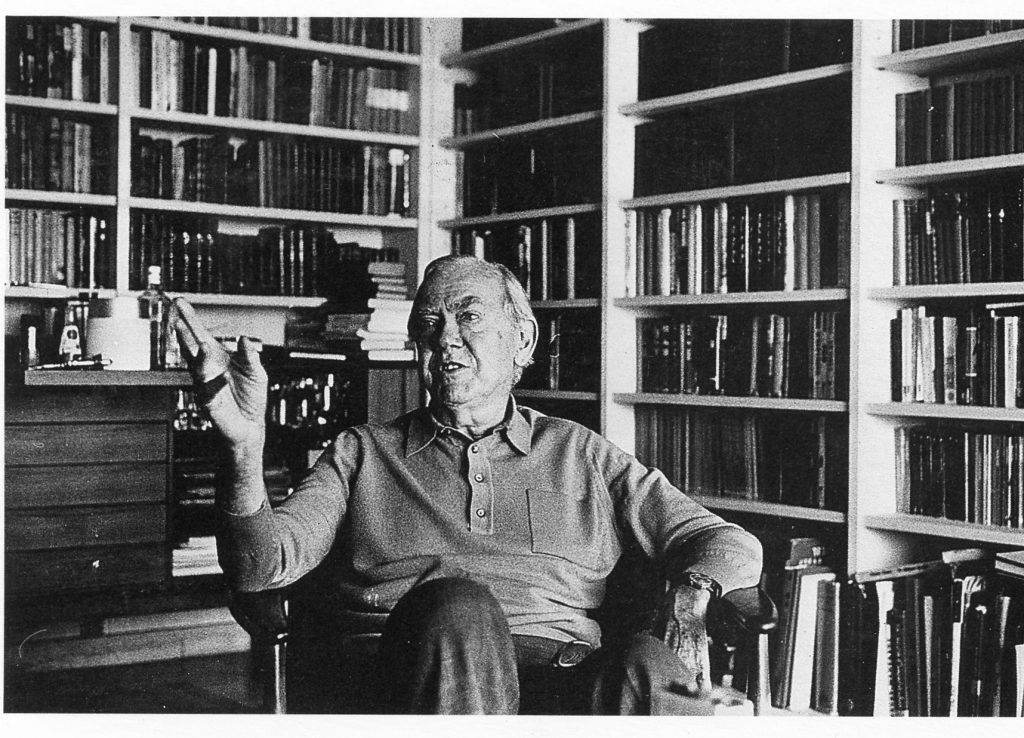

Image: Graham Greene.