Iran’s major TV show on cinema, Seven, is unlike any other country’s program on movies. Instead of promoting the Iranian cinema, Seven is designed to undermine it. Behrouz Afkhami, a veteran filmmaker, took over Seven in 2015. He has made important movies in the past, such as Shokran (“Hemlock,” 2000) and Govkuni (“The River’s End,” 2004). He also recently made Azar, Shahdokht, Parviz and Others (2014), based on a story by his wife, Marjan Shirmohammadi. His incarnation of Seven — while updating décor and style — is seeking to improve its ratings with controversy. It puts the critics’ egos first and advances reactionary political views. The reviews are not there to inform, but to attack.

Seven’s veteran film critic, Massoud Farassati, was educated in Italy and France, and made his name editing film journals and writing books, including works on Iranian war movies. Early in 1988, Farassati wrote a positive review of Abbas Kiarostami’s film Where Is the Friend’s Home? in Soroush Weekly, though he later disowned it, describing his review as “a very bad critique.”

In the intervening years, Farassati had made his career by chastising international film festivals and directors like Kiarostami and Dariush Mehrjui, whom he cast as the Iranian intellectuals who make films for the festivals. To Farassati, Kiarostami did a great disservice to Iranian cinema by showing the path to the world-renowned festivals. Even Farassati’s elegy for Kiarostami was a jab and a boast to Farassati’s ego. His remarks, titled “His Life and Nothing More,” plays with the name of Kiarostami’s 1992 film Life and Nothing More… to imply that Kiarostami’s life but not his work was worthwhile. Yet Farassati has spent much time in his criticisms censuring not just the works but also Kiarostami himself. He also praised Kiarostami for “welcoming criticism,” by stating that Kiarostami considered his criticism very valuable.

One of Farassati’s major targets has been Ashgar Farhadi. He argues that A Separation is a bad film, not only in cinematography and mise-en-scène but also in character development and narrative. He believes Iranians should not be happy and proud that the film won the Oscar. Instead, he argues that all of the West’s awards are politicized, meaning the film didn’t get its awards because of artistic merit.  Farhadi’s film was almost unanimously loved and appreciated by critics and viewers across the world, but for Farassati, the Iranian directors acknowledged by the West are selling out by catering to Western tastes and prejudices. This perspective defines Farassati’s criticism.

Farhadi’s film was almost unanimously loved and appreciated by critics and viewers across the world, but for Farassati, the Iranian directors acknowledged by the West are selling out by catering to Western tastes and prejudices. This perspective defines Farassati’s criticism.

In another episode of Seven, the critics argue that given films of equal merit, the Cannes festival will favor a film that deals with LGBT issues. Everyone’s judgment is at some level influenced by different personal, political, and ethical perspectives, but it’s also Farassati’s judgment — and his own bias toward Iranian sacred defense films — that has perverted his vision of cinema. Farassati also argues that these films tend to be dark in their subject matter and thus provide a bad image of Iran for the West. They reinforce negative beliefs about Iran, which in certain ways can be true. But of course he also knows that many major award-winning films from all over the world have been critical of their own societies and governments. This is what artists do.

In a recent program, Farassati used the website Metacritic to prove that Salesman (2016), Farhadi’s Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Language Film, was “pre-bad” (a term he has made-up), pointing out that it had the lowest ranking in a list of Farahadi’s movies. Technically, this wasn’t true; The Beautiful City was ranked lower, and with its U.S.-release and added reviews, Salesman is now ranked at eighty-four percent. But more importantly, if Farassati believes in the validity of other established critics, then he should accept that A Separation — with a ninety-five percent ranking — is a major film. Instead, he conveniently uses the information when it’s to his advantage. For example, in a roundtable, he tried to justify his view of Hitchcock by pointing out that Vertigo was voted number one on Sight and Sound’s “Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time.” If Farassati truly believes in such rankings, maybe he should reconsider his view of Kiarostami’s Close Up, which is ranked at number forty-two.

In a recent program, Farassati used the website Metacritic to prove that Salesman (2016), Farhadi’s Oscar nominee for Best Foreign Language Film, was “pre-bad” (a term he has made-up), pointing out that it had the lowest ranking in a list of Farahadi’s movies. Technically, this wasn’t true; The Beautiful City was ranked lower, and with its U.S.-release and added reviews, Salesman is now ranked at eighty-four percent. But more importantly, if Farassati believes in the validity of other established critics, then he should accept that A Separation — with a ninety-five percent ranking — is a major film. Instead, he conveniently uses the information when it’s to his advantage. For example, in a roundtable, he tried to justify his view of Hitchcock by pointing out that Vertigo was voted number one on Sight and Sound’s “Top 50 Greatest Films of All Time.” If Farassati truly believes in such rankings, maybe he should reconsider his view of Kiarostami’s Close Up, which is ranked at number forty-two.

Farassati likes to promote the most revered Western filmmakers, like John Ford and Alfred Hitchcock, and he focuses on the value of their films, which is strange coming from a person who seems to champion a nativist, anti-West cinema for Iran. But that is just one of his contradictions. Ultimately, his criticism of Iranian cinema is not grounded in the films themselves. Just as he changed his view on Kiarosatmi’s early film, his view of Iranian cinema is personally and politically motivated, and his condemnation is not just limited to those who win awards in the festivals. Farassati is under the misguided notion that criticism means censure. He also attacks films by conservative filmmakers, such as Masoud Dehnamaki, and films funded by the government, such as Majid Majidi’s Muhammad: The Messenger of God. In fact, while he acts like he is defending cinema and Iran, he is rebuking the whole of Iranian cinema.

Farassati talks of professionalism, but calling films “garbage” is unprofessional — and predictable. While watching Seven, you know what he will say before he says it. He will begin with some snide remark or by bluntly stating “this is a bad film”; then he’ll bad-mouth a director’s personality or politics and put down the film with clever and mean-spirited comments. Don’t expect an in-depth critique from Seven. As Farassti recalled, Kiarostami once told him that he respected his opinion but his tone was a problem. Now, all that remains of the critic is tone. Maybe critiquing what others are afraid to voice is an important service. Kiarostami did have many detractors in Iran. Maybe in the past Farassati provided some needed perspective, even valuable critique, but he has turned into a caricature of himself. There is even a satirical Facebook page under his name that pokes fun at his writing. No wonder one of his latest books is titled Lezzat Naghd (“Pleasure of Criticism”). He takes no pleasure in the cinema itself. He no longer enjoys or expects to learn something from the movies. What matters is Farassati, his opinion, and the pleasure he derives from slander and the controversies he creates.

Why is such a program the main cinema show on Iranian TV? I would venture to guess that it may have something to do with the divide between Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB) and the movie industry, which is run by a different government organization. IRIB seems to disdain Iranian movies. Filmmakers often complain about not being given slots for their trailers.

Iranian TV is losing viewers who are turning to social media and satellite channels from outside Iran. There is also a home entertainment option under the watch of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, which allows greater freedom of expression. Filmmakers can make their series and distribute the shows weekly as DVDs through shops. An example of such a series is the recent Shahrzad that is far more popular than any series on TV.

Fortunately, Iranian films are doing fine. Box-office revenues were up last year, and Salesman became Iran’s highest-grossing film of all time. Seven is not the only place for those who have an interest in Iranian cinema. Movies are discussed on dedicated websites and in various social media groups. There are also a number of film journals such as Film Magazine, Cinema and Literature, and the monthly publication for the Arts and Experience Cinema, which is a new branch of Iranian cinema focusing on arthouse films and films that won’t get permission for wider public screenings.

*

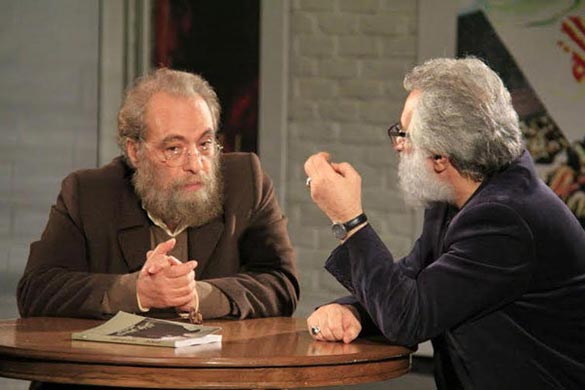

Lead image: Set of Seven, with Massoud Farassati (left) and Behrouz Afkhami (right).