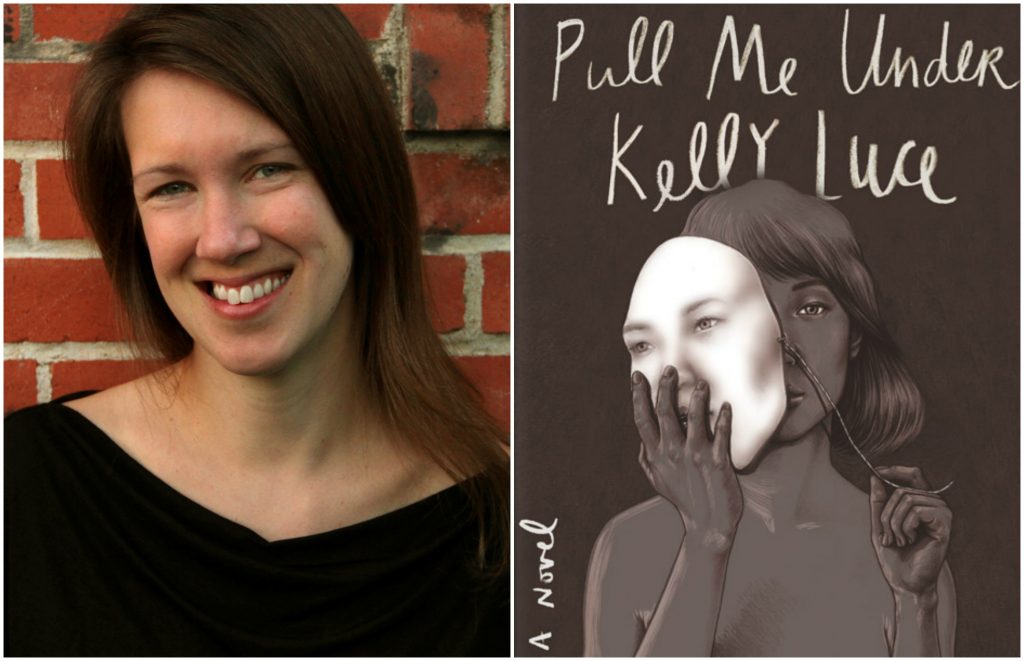

At the beginning of Kelly Luce’s novel Pull Me Under, twelve-year-old Chizuru Akitani fatally stabs her bully, Tomoya Yu, with a letter opener from her teacher’s desk. Retained for the entirety of her adolescence in a juvenile detention center and disowned by her father, Chizuru sets about the difficult work of reinventing herself: she picks up running and loses the weight that attracted Tomoya Yu’s ridicule, she attempts to grapple with events of the day she snapped.

Granted the opportunity to leave Japan to attend college in Colorado, Chizuru relinquishes her citizenship and leaves the event that has defined her personhood for the majority of her life, far across an ocean. In the intervening years, Chizuru changes her name to Rio, becomes a nurse and starts a family unaware of her past. Her life becomes jigsaw puzzles and playdates, her greatest concern whether or not her family will relocate to a tacky suburban community called Tuscany Terrace. That is, until her father, Living National Treasure violinist Hiro Akitani, passes away and Rio returns to Japan for the first time in twenty years.

At turns searing and sincere, Luce explores the implications of identity and the weight of secrecy. Pull Me Under explores and dismantles the trope of “woman with a dark secret resists suburbia and its trappings” that usually manifests in unfortunate, infantilizing “Girl” thrillers — Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc. — books that represent their female protagonists less as dark, complicated labyrinths, and more like guns with the safety off: impulsive, immature, desperate with bitterly predictable inner lives.

Through her sparse, precise prose, Luce fortunately spares us, presenting instead a realistic, powerful rendering of trauma and womanhood. Rio’s darkness — characterized by Luce as a “black organ” — lends beautifully to both the empathy and the tension of the novel. Its suspense found me white-knuckling my way through the last seventy or so pages of the book.

Recently, I had the opportunity to speak with Luce about Pull Me Under, the phenomenon of kireru, writers who [don’t] run, and Vatican astronomers.

*

How was this book born? Did you conceive of Rio as a character first, or were you more interested about writing about a character in her particular circumstances?

When I living in Japan, I learned about the phenomenon of kireru, which means “to snap.” The concept of snapping and committing violence under pressure isn’t foreign to us, but the people who were snapping — namely, young children, including girls — surprised me. I was teaching junior high at this time, and I wondered whether any of my students, cheery or well-behaved on the surface, were capable of this. So the book was born from a question: what would have to happen in a child’s life for her to do this? And as I started to answer that question, Chizuru (Rio) was born.

What’s interesting about Rio — you know, besides the whole stabbing her classmate thing — is that she spends the entire novel as a liminal figure no matter which space she’s in. It’s in part due to her background, being half-Japanese, but extends into her American experience in subtler ways: her resistance to the pull of suburbia, for instance. When moving past her childhood and the incident, what was your process of imagining and forming Rio into an adult, removed from the incident by distance and time?

I wrote the scenes of her as a child first, for the most part, and those scenes are where I looked for clues as to how she would be as an adult. There are certain characteristics about a person that don’t change, and they manifest pretty early. I wanted to figure out those true-self traits first, before I began to imagine how her childhood experiences and trauma affected her personality and way of being in the world. Not because our experiences don’t affect us, but I hate when books try to explain every a character’s every action with a one-to-one correlation between said action and past trauma. Not everything we do has a direct precursor or even reasonable explanation.

I knew Rio had always been strong-willed and compulsive, a bit like her father, which both helped her and held her back. Her will to keep running and get in shape turns into a lifelong hobby/obsession with trail running, for example, but that same willpower is the tool she uses to keep her family in the dark about her past, to create and sustain a new narrative and identity for herself in America after leaving Japan. But then there are the things she can’t control in this new narrative, namely, the people in it that she loves — her husband and her daughter. Imagining her relationships with them are what I think guided me most in creating her adult self.

Yes! I so appreciated that the threads of her trauma were not so obvious or direct. It’s interesting that you gave Rio her obsession with running — The Atlantic had a whole article about authors who run last year, where they attempted to find some kind of a correlation. Do you run?

No, I hate running. I mean, I don’t mind doing it if I’m playing a game or chasing something — namely, a frisbee (I play Ultimate) but I get super bored just jogging aimlessly. My mind rebels. Distance running is also shitty for your knees, and I want to keep mine as long as possible.

The people I know who are hardcore runners are all masters of discipline, at least compared to me. Maybe they’re also the type of writers that write every day, on a schedule — which I do not. I think Rio is like that, though. She has to be disciplined in order to keep her life together, keep her secret safe.

You said you worked on this novel on and off for eight years (something I cannot help but notice, as I transcribe this interview, might be its own distance sport), was there anything you read that informed your work on it?

I didn’t really try to curate my reading, though, or be precious about my reading diet as I wrote my own book. A few books I loved that may or may not have influenced the novel (though I suppose everything we love influences us) are Suzanna Jones’ The Earthquake Bird, which is just a perfect literary and psychological mystery set in Japan with a gorgeous voice and killer love story. And my friend Andy Couturier’s A Different Kind of Luxury, a beautiful accounting of the ways people in Japan’s countryside are living fulfilling, sustainable lives. Kawabata’s Palm-of-the-Hand Stories were never far from my side. I also listen/listened to a lot of violin concertos and Japanese music — artists like Pizzicato Five, Kishi Bashi, Angela Aki (who is from Tokushima, where the novel is set), Kaguyahime, Cornelius, and Takako Minekawa.

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to me. If I can ask, what are you working on now?

I’m working on my next novel. It’s still early in the process, but it involves female homelessness, prenatal memory, the so-called conflict between science and faith, and a Franciscan brother who is an astronomer at the Vatican. (Yes, the Vatican has astronomers, and quite an amazing observatory!)

*

Pull Me Under is out this month from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Find out more about Luce’s work at kellyluce.com, or follow her on Twitter @lucekel.