“Milt and Moose,” short fiction by Eileen Pollack, appeared in the Winter 1999 issue of MQR.

*

“Moose, Moose, they won’t let me go out like a gentleman.” The dentist held out his hands, which trembled in the sharp autumn air. He was tall, silver haired, with a neck curved from years of bending over his patients. He looked like one of his instruments—the curved mirror, or the explorer, with its gently hooked tip. “It’s nothing serious,” he told his friend Moose. “It’s not Parkinson’s.” The dentist, whose name was Milt, brought his key toward the lock on his Impala, which was parked in front of his own split-level ranch house, directly across from his friend Moose’s split-level ranch. Milt jabbed the key toward the lock, which thank God it went into. “My hands are in a patient’s mouth, it’s like they’re too busy to shake. But people see a needle coming, a drill. . . .”

Moose chopped the air with his own hands, thick and steady as spades. “Ahh, you think people care you’re getting older? They call. They make appointments.”

“That’s the trouble! They won’t let me go out, now, while I’m still . . . respected.” Milt looked up at the maple at the edge of his lawn, purple-red-yellow-orange against the bright bright blue of the morning sky, the leaves bursting with . . . vivacity, Milt thought. Why did people think autumn was a sad time? He’d been a dentist for forty-one years and today was his last day, he was selling the building, the practice, this house, he and Gretta were walking away and starting over. He felt he might burst into a glory of colored leaves himself. The maple was taller than his house. When he looked upward at the leaves, his heart swelled, as his heart still swelled to see his wife at the foot of their bed, undressing for sleep. He’d planted the tree on a Sunday afternoon in May of ’49. The next morning he’d gone down to the office, and a windstorm blew up. When he drove home for lunch — in those days before the children, he still drove home to see his wife for lunch — Gretta was out in the battering wind, trying to wrap her body around the young tree to keep it from uprooting, the rain wetting her green housedress so it clung thinly to her back, and her hair clung to the fabric. He wanted to take Gretta right there, on the lawn — Let the tree blow to hell! — but he’d gotten her inside first, where she pulled the wet dress up and over her head, uncovering the dark moist hollows beneath her arms, and he’d gone to her, nearly dying from gratitude. Her brassiere was wet in his hands as he unhooked it, her nipples cold and damp to his mouth, and she’d run her hands through his own damp hair as he was doing this, on either side of his neck, and this made him so eager he wouldn’t let her get away to take her usual precautions and their son Joel was conceived.

“You ought to be honored,” Moose was saying. “Look at me. I give the dairy a year, at the outside. Home delivery? It’s not exactly as if I’m providing a product people can’t get elsewhere.”

Milt hadn’t given his friend credit for such self-awareness. Gretta often said it would be easier to pick up milk at the supermarket, when she bought everything else. First you had to remember to leave the note. Then the delivery man clattered up your porch at five in the morning. You forgot to bring it in, the milk and cottage cheese sat there spoiling all day.

“Well, I can’t stand here gabbing, I’m dying on my feet.” Moose rubbed his shoulders thoughtfully. Even at sixty-nine he was built like a gallon milk-carton. That’s how long they’d known each other, sixty-nine years. Their fathers owned dairy farms on the same road, and every morning Milt and Moose hiked down to school together—skied, sometimes, in winter. Summers they drove the milk wagon to the Dairytime warehouse. They’d gone away to the war the same week and come back the same month and built houses across the street from each other. Milt knew every twitch of the other man’s habits—how Moose got up in the cold dark and drove down to the warehouse to organize the deliveries, then drove home for a second breakfast at 8:30, just when Milt himself was heading out to his car. They’d bullshit by the curb—the weather, the kids, that putz Reagan—until Moose started to rub his shoulders and found an excuse to go in. Milt and Moose never spoke of this, but Milt knew that Moose’s wife Cynthia would still be in her nightgown, she’d gotten the kids off to school and gone back to lie down, and this was the time she and Moose made love.

She’d been a looker, that Cynthie. Petite, with a waist you could put one hand around—one of Moose’s hands, at any rate. A sharp dresser—her folks owned the hardware store, they could afford to keep her in those nice sweaters Milt remembered from tenth grade. He would have asked her out himself, but Moose got up the nerve first, and Cynthie didn’t say no. Moose was a handsome guy then, with that build on him, and Milt so thin he was embarrassed to look down at his own legs in P.E.

He glanced across the street now, past the unkempt shrubbery. Cynthie wasn’t in their bed. No one was in their bed. What did Moose do when he woke from his nap and no Cynthie? The grief of it all, a man trying to rub his own back, to pleasure his own body! Milt slid into the Impala and slammed the door on this thought—his friend Moose with his hand in his pants, cleaning up the mess after. How long had it been since he, Milt Rothstein, had laid a hand on himself? In the service, sure. In dent school, once or twice, after a rough exam. Not since he’d married Gretta. But who knew what a man might do, alone, he couldn’t sleep, he had needs?

Jesus, what was all this sex stuff? Sure, Milt had pleasurable thoughts sometimes, especially if an attractive woman was in the chair. But with Gretta, he didn’t have to think about it all day. Sex was only, well, a language, unimportant in itself, unless you had something to say and someone to say it to. He glanced back at his own house, and when he didn’t see a light—no one in the bedroom, no one passing back and forth in the kitchen—his heart klopped.

No, no, it was all right. He remembered now. He’d awakened to find Gretta up and dressed, leaning over him. “I have an appointment,” she said. “A check-up. You know, darling, I go every year. It’s what they recommend.” She had fiddled with an earring. “I could wait until we move, but it might take a while to find someone down there. And who knows what kind of doctors they have, preying on older people. Nincompoops who couldn’t make a success of it up North.” He’d let this go as truth, returned her kiss and rolled over, but now it seemed she’d gone on a bit longer than she needed, and Gretta never went on. She never fussed with her jewelry.

“So don’t forget,” Moose yawned. “There’s a Rotary meeting tonight. I shouldn’t tell you this, but the boys are planning a little surprise.”

Just what he needed—jokes that weren’t jokes, the buffoonery of old men.

“And the award!” Moose said, laughing. “Don’t forget, you’re getting that award!”

Worse than buffoonery, a lie. Most Wednesday evenings, when it came time to walk to the Homestead Restaurant, Milt thought: Who needs it, a bunch of hick businessmen who prefer that putz Reagan to Carter—who was, Milt had always thought, even before it was the popular opinion, a good man. Better to be in his own home eating Gretta’s mandarin chicken, or maybe a nice blintz and sour cream, than tearing away at the fatty prime rib in the Homestead’s back room. They’d have kicked him out long ago, but the recording secretary was one of Milt’s patients, so, every week, no matter if Milt was there or not, a check went next to his name, and Andy Atkins sent the attendance records to the state chapter, and here Milt was, retiring, and the state chapter decided to honor him for forty years’ perfect attendance. A certificate, a plaque—for what! For eating dinner with his wife.

Moose started up the walk to his own wifeless house, then turned back toward his friend. “Meant to warn you . . . Sonny found out this is your last day. Boy, he’s in bad shape, sitting on your stoop, bellowing like a behayma. ‘Oh, how could Doc do it to me, who’s going to take care of me?’ He was yelling this, top of his lungs, five o’clock this morning.”

Milt shook the Impala’s steering wheel, the way he used to shake Joel by the shoulders before the kid straightened out. “Haven’t I done enough? I don’t deserve a little peace?”

“I’m only telling you, it shouldn’t be a shock when he’s sitting there like one of those, you know, stone things with the ugly mugs, scaring away your nine o’clock appointment.”

Why was Milt so irritated at his friend for saying this? It was as if Moose were using this other man, this cripple, to say what Moose couldn’t say himself—Don’t go,you’re deserting me, you have no right to leave. Before Milt knew what he’d done he’d thrown the Impala into gear and was accelerating away from the curb without so much as a wave or nod, See you at six for Rotary, nothing. His urgency, his fear that someone would throw a net over his car and trap him, pursued him to the corner. He might not have stopped at the stop sign, but who should be waiting beside it but Carolyn Miller, holding up her palm, and Milt was too much a gentleman to floor the gas and spit gravel to get away from her.

Carolyn wore a pink tennis outfit at exactly the right length for a woman in her sixties who still had nice legs, and she spoke in that sweet voice she’d used all those years ago, before Milt gave her his dental-school ring and she assumed he would follow it up with a diamond, which he didn’t, and she flushed his ring down the john.

She leaned in through the window. “Milt, I know this is presumptuous of me, but the twins are coming for Thanksgiving.”

Milt’s foot twitched on the gas pedal.

“They just pleaded and pleaded. ‘Ma, we know Dr. Rothstein’s retiring, but maybe he could see us one last time?'”

Carolyn held out her hands as if one twin were in each. The girls were in their late thirties, married to twin brothers in Oneonta, and they still drove down to Milt for their dental work, whether because they couldn’t bear to go to someone new or because their mother encouraged them. Even in their teens, Carolyn had brought them to appointments, as if to say, See? For all I wouldn’t let you touch me, Milt Rothstein, I am not a frigid woman. Why should I have slept with a man who wouldn’t promise he would marry me? But Milt hadn’t done much more with Gretta before their marriage than he’d done with Carolyn. He’d just known from the way Gretta kissed him that first night, on the stoop of her flat in the Village, the way Gretta moved her lips against his, the way she curved her hand around his neck, she didn’t regard sex as, what would you call it, a trade—for a husband, a child, a nice house. With that kiss, Gretta set blooming in his head the knowledge of what their married life would be. He’d never even pictured having intercourse with Carolyn Tomaschevsky, or any of the other girls from home. Except, oh, when he saw them in their gym suits, he wondered what their bare breasts might look like—large or small, round or tipped. He’d grown up with them, they were like his sisters. But more, he sensed none of them would do for their husbands what Gretta would do for him. What she in fact did do, though he never asked this or expected it. And she’d done it with such . . . sweetness, there was no other word for it, such . . . enjoyment, he could only moan like a boy and do for her what she’d done for him.

He saw Carolyn staring at his lap, and Milt grew furious that she would think he was responding to her—that short skirt, that insincere voice.

“Oh, Milt.” She adjusted the visor of her tennis cap and looked up at the sun. “It’s all going to fall apart now,” as if he’d pulled a brick from a dam and started a flood that would wash down the hill all these pleasant homes.

“What fall apart? There’s a time for everything. The kids are grown.” By which he meant he wasn’t about to keep his practice going until he dropped dead beside the chair just so Stephanie and Lydia Miller would never have to pay ninety bucks per filling to someone who had jilted their mother and still felt guilty about it. “Call Art Spivak, he can fix them up over the holiday.”

“Oh, Art Spivak,” she said. “I know all about Art Spivak,” which most of them did. Ben and Adele’s boy. A nice kid. All right, too nice. A nebbish, Milt admitted it. Who else was going to take over a practice in a nowhere town like this? Okay, so Art Spivak wasn’t Mr. Personality. Milt had seen some of the kid’s work—nice conservative dentistry. Artie Spivak wasn’t going to ruin anyone’s mouth, he’d be the first one to send the tough cases to a specialist. And a grateful kid, must have thanked Milt a thousand times for all the breaks—putting in that good word to the admissions board at N.Y.U., handing over his practice for beans, and not just the office and the equipment, but the patients’ records, the letter saying Milt hoped everyone would show Dr. Spivak the same courtesy they’d shown Milt.

“If the girls don’t want to see Art Spivak, there’s nothing I can say,” and he drove off with relief, as if he’d escaped whatever beast he’d been dreading.

Sonny Kuppelstein was not, as Moose predicted, making a gargoyle of himself on the steps to Milt’s office. There was only Milt’s brother, Marv, an optometrist who shared the building with Milt. Marv was bending laboriously to pick up the Times; he might have been a hippopotamus on his hind legs, stooping to pick up a newspaper with its hoof, or whatever hippos had.

“You know, Miltie,” Marv grunted and snagged the paper, “you really sold me down the river. That candyass Spivak, he came snooping around here yesterday. ‘Oh, hi, Dr. Rothstein, nice to see you,’ and he shakes my hand in that way, I have to wipe my palm on my trousers. Next thing, he’s asking, ‘So, what does your brother charge you rent?’ And when I tell him my brother doesn’t charge me rent, only utilities—what does he think, a brother collects rent from a brother?—this candyass Spivak says, ‘Gee, Dr. Rothstein, I don’t think I can keep up the mortgage myself, I hope you don’t mind, but I’m going to have to ask you to kick in your share.’ Three hundred a month! Plus utilities. And the plowing service in the winter, and a quarter of the property tax on top!”

“Damn it, Marv, you can’t expect the kid to carry the building himself. I gave you the chance. You could have bought the building for pocket change, and you’d be charging him rent.”

Marv slapped Milt’s forearm with the rolled newspaper. “You could have kept it in your name until I closed up shop.”

“I’m moving to North Carolina! I should have to worry the furnace here goes on the fritz some freezing night in February?”

“So, who told you to move? Not even Miami! Not a Jew on that island, I’ll bet.”

Yeah, and if it had been Miami, Marv already would have tagged along and bought the condo next door, the way he’d tagged along to the Army, then to N.Y.U., though thank God he had no taste for dentistry—saliva and bloody gauze didn’t appeal to him. An older brother, tagging after the younger. It made Milt’s skin itch.

Well, there was a limit. Wasn’t there a limit? Milt wanted to be rid of it all—the building, the house, the worries about taxes and malpractice. He was disencumbering himself of the entanglements of his life, Milt thought, though it wasn’t a word he’d ever used,disencumbering, as if retirement had its own vocabulary. When he said that word, disencumbering, he saw a man struggling out of his suspenders and unbuttoning his pants, though Milt had never worn suspenders and no longer knew any man who did.

“You’ll be singing a different tune this winter,” he told Marv, “when you’re shoveling out from under a blizzard, and Gretta and I are strolling on the beach.”

“Beach, beach, don’t talk to me about no beaches. You bite a sandwich, a piece of fruit, what do you get except grit on your tongue?” Marv extended his own fleshy tongue and fingered it for an elusive grain. “And the filth! The bloody needles, those plastic whatyacallits, those women’s things. And hot, hot. All that sun, you’ve got to worry you’ll get a cancer. Tell me, Johnny Weissmuller, when was the last time you took a swim?”

The last time? It couldn’t have been Atlantic City, a godawful honkytonk of a place even in the fifties. No, the last time was, oh, ’65, ’66. That pervert Al Marshiniac down at the Inn, he tells all the men, Listen, nobody much uses the pool here. For a few bucks you can have yourselves a membership, bring the wives up after work, relax. And Milt thought, Sure, why not, it was worth fifty bucks just to see Gretta in a suit. And maybe it was the sight of her in that simple blue one-piece, the long soft beauty of her legs, arms, and neck, the hair wound and pinned up, maybe that was what put it in Milt’s head to wonder where that weasel Marshiniac went after he’d greeted them in the lobby, the six or seven couples who came up every Tuesday after dinner. Milt followed his question to the men’s room, the last stall, and there was that little bastard with his eye pressed to a hole above the tank. And when Milt pulled Marshiniac away and put his own eye to the hole, who was he looking at but his own wife, stepping out of her suit, twisting so he could see the dimpling of her shoulder, the white curve of one breast, the rich heaviness of her buttocks. For a moment he felt an ecstatic gratitude, as if he’d looked through a telescope at some dazzling ringed planet and it seemed heartbreakingly beyond a man’s grasp, and yet, if he reached out, he could touch this planet, bring it home. Then Marshiniac whimpered behind him and Milt turned and slugged the guy so hard his head dented the opposite partition, the first and only time Milt Rothstein, veteran of some of the worst fighting in the Pacific theater of operations, ever used his fists on another human being. And that had been the last time he’d seen Gretta in a suit, it was as if swimming had entirely dropped out of their language.

“You want to lie on some beach with a bunch of strangers, okay. I still say you could have kept the building.” Marv mim icked Art Spivak’s milquetoasty voice. “‘I don’t mean to inconvenience you, Dr. Rothstein, but I could never rest, knowing all those newspapers are down there, they could go up by themselves, spontaneous combustion, let alone from a spark.’ Candy ass kid, afraid of a stack of paper.”

Milt wanted to snatch the Times from his brother’s hand and smack him on the head. Draykopf! Of course the papers were a fire hazard. Marv had copies of the Times dating back to Pearl Harbor. When Milt’s cellar filled up, about the time of Korea, Marv begged Joe Potter, the podiatrist next door, to let him use his cellar. Near the start of Vietnam, he’d slipped Eva Gorman a fifty to take over the cellar of her beauty shop, and so on down the street, through that Panama fiasco, and that Gulf thing. What did Marv think, after he retired he was going to sit around and read all the articles he hadn’t read the first go-round, he’d become a big-shot military strategist and consult for the Pentagon? Or maybe he’d get the chance to live his life over, all the current events he’d missed, 1940 to the present? Except that Artie Spivak was right, the entire system of paper-filled basements would go up in flames first, like one of those coal-mining towns in Pennsylvania, the houses collapsing into sinkholes, the town smoldering for years.

“Marv, Artie Spivak has every right in the world to ask you to clear out that crap.” Milt tried to insinuate himself past his brother’s bulk into the foyer they shared. “I can’t stand here gabbing all day, I’ve got to straighten up for my nine o’clock.”

“You don’t think I have my own appointment to straighten up for?”

Hah! Milt laughed to himself. You shtunk, you haven’t done one thing to straighten up that office in forty years. That fish tank, everything dead in there except the hermit crab Milt’s grandson Lyman brought home from camp in Maine, the water in the tank so black the poor creature would outgrow its shell and go looking for another and not find it.

“Good morning, Dr. Rothstein.” A pleasant girl in her early thirties walked up the steps. “And hello to you, too, Dr. Rothstein.” She giggled at her joke. Plump, a sweet face . . . What was her name, Something Woods? She wore a pair of Marv’s owly tortoiseshells, the kind of frames even Milt knew had gone out of fashion in the seventies. What’s the matter, Milt asked his brother once, you never heard ofselection? And that ugly zhlub of a brother of his picked his nose and flicked away Milt’s suggestion with whatever treasure he’d excavated, it was just about the only thing Marv didn’t save. Selection? Forget selection. The patients sit there forever. “How do you like this one, Dr. Rothstein? What about these?” Glasses is glasses! They’re for how you see, not how you look. Marv offered only three choices—the big tortoiseshells for the women (Gretta hated her pair, she only wore them because how would it seem, she didn’t go to her brother-in-law for glasses), and black wire aviator frames for the men (Milt, Moose, and Marv each wore a pair), and those sparkly frames with points for the kids—blue for boys, pink for girls. If you stood by the traffic light long enough you’d see nearly everyone in town go past in those tortoiseshells, or those black aviators, or those blue or pink sparklers. Marv didn’t have his own kids—whether it was his fault or Flo’s, Milt never found the tact to ask—but here was an entire population whose appearance Marv had influenced as surely as if he’d shtupped every woman who sat in his chair—which he nearly did, the way he climbed in their laps with that instrument of his, peering in their eyes. Oh Marv, Marv, with your dusty newspapers and your farshtunkeneh fish tank! You’re my older brother, I tried my hardest to look out for you, but for Almighty sake, it’s supposed to be the other way around!

“Dr. Rothstein? Could we go in now? I have to bring some cupcakes to my son’s class at ten o’clock.”

“Have a little patience,” Marv cautioned her. “This is my brother’s last day, a man doesn’t rush such a moment.” He turned to Milt. “You tell that pisher Spivak I don’t pay more than utilities, and the newspapers stay. Then you can go enjoy your retirement.”

Milt’s receptionist Olivia Golden was packing into a cardboard box the orange-juice can covered with yellowed macaroni shells her son Hunkie had glued for her in elementary school, the golden hammer Hunkie had been awarded for his talents in shop, a stack of back issues of McCalls, a bag of butterscotch candies. She plucked a tissue from a holder decorated with a wool jacket she’d crocheted herself, swabbed her eyes, blew her nose, then tossed the tissue in the wastebasket. Sure Milt felt bad, but was it his fault Artie Spivak preferred to work with a trained hygienist instead of a receptionist who could barely keep the billing and insurance procedures straight? Two-handed dentistry was dead, dead. The kid already had hired a girl who could clean teeth in the back chair while he himself, Artie, did the tough work out front. Wasn’t that why Milt had installed the second chair all those years ago? He just, to tell the truth, hadn’t gotten around to hiring a girl. He liked his privacy, and he was too . . . sensitive to work so close to a strange woman. Artie Spivak was a single man, no reason he couldn’t hire a hygienist. Was Olivia a slave, a concubine, she should be passed along, master to master? Milt did what he could to soften things—salary and insurance through the end of the yearhe tried to pull a string to get her a place as an admissions clerk at the hospital. Was it his fault they were laying people off?

“Oh Doctor.” Olivia plucked the last tissue, and it upset Milt, seeing that last tissue pop up and not another to take its place. That, plus Milt felt responsible for anyone crying in his office, as if he should have foreseen the trouble and taken the proper prophylactic measures, or, neglecting that, should accomplish whatever restorative actions were required.

“Olivia, get a hold on yourself. Nothing is so terrible. No one is sick.” He told himself to stop right there, but next thing he was telling Olivia how he’d decided three months’ salary wasn’t enough, after all her years of service, he was doubling it to six.

“Oh, thank you, Doctor!” she said, even before he finished, in a way that made Milt see what a pigeon he was, she’d had this show planned. He wouldn’t have put it past her, the way she’d used up that last tissue just at the right moment.

“Doctor, I should tell you, there’s one more thing. . . .”

Which he wasn’t about to give her, lay it on thick as she might.

“Sonny Kuppelstein was here this morning. Doctor, you say he’s a harmless man, but this morning, you might have said otherwise. I don’t know what he was shouting, but I wouldn’t let him in, and he finally ran off.” She unwrapped one of the butterscotches and palmed it in her mouth in the manner of a woman swallowing a tranquilizer. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he comes back.”

Was this what the cramping of his intestines was about, the dread of Sonny Kuppelstein throwing a scene? “Please,” he told his receptionist, “don’t let him in if I’m working on a patient.”

Tearfully, she nodded, though both of them knew how ineffectual she was in holding back Sonny Kuppelstein if he wanted to come in.

In the privacy of his inner office Milt unbuttoned his shirt and hung it on the hook behind the darkroom door, then slipped into the white vinyl jacket that previously had hung on that hook, snapping it along the shoulder. He flipped open the sterilizer and used tongs to lift the instruments from the steam, wishing he hadn’t thrown these into the bargain. Did a musician give away his violin just because he stopped giving concerts? Then Milt thought, Where was the comparison? A violinist could play for his own enjoyment, at home, but what would a dentist do, work on his own mouth, or his wife’s?

“Miss Sink is here,” Olivia said from the doorway, and she handed him the large index card on which was noted the dental biography of Geneva Sink, one of Milt’s first and oldest patients. When he opened his practice, he’d been so grateful for Geneva Sink’s trust he’d charged her half the going fee. He still charged her half price, but whenever Olivia handed her a bill, Geneva Sink stood there calculating and recalculating, as if Milt had gotten the addition wrong. She’d been his math teacher in high school, and he had the painful memory of standing before a chalked equation for half an hour, and when that didn’t improve his computational skills, having his forehead smacked against the board.

“I suppose you think I’m going to offer you good wishes.” She stood beside his chair, straight as a rubber-tipped pointer. Her hands didn’t shake. “I am 93 years old and the probability is high that I will not live more than a few years. One would think that one’s dentist would have the courtesy to wait until his oldest patient died before he retired.” She stood waiting for an answer, as if life were a math problem Milt was too dull to comprehend.

“Geneva,” he said, though he’d never called her anything but Miss Sink—”speaking as one adult to another, I’ve never given you cause for complaint.”

“Now Milton. Speaking as one adult to another, I thought you would be able to tell a compliment from a complaint. I certainly didn’t hear anyone begging me to stay at my post when I stepped down from teaching.” She sat sideways on his chair, then drew up her legs to the footrest. “Why don’t you take care of everything that might need taking care of, and I won’t have to trouble Arthur Spivak, who, though he has a better head for mathematics than you do, could barely, I am convinced, even now, tie his shoe.” She crossed her bony arms, closed her eyes and opened her mouth in a tense grin, as if she wanted Milt to spare extra work not only for Artie Spivak, but also the undertaker.

And so Milt clipped a bib across her age-flattened chest and went about his business—the excavator, the drill, the amalgam and mercury, pack, shape, all done, only a few sharp breaths from Geneva Sink to remind him this was a living woman he worked on. She was ninety-three years old, she would die soon and take with her all her knowledge of mathematics, as Milt himself would die and take with him all the learning and intuition and dexterity acquired in four decades as a dentist. That was a man’s life. He devised his own secret technique for fabricating an anterior crown, taught himself the best way to remove an impacted lower wisdom tooth, then he went to his grave and whoever took his place started over. Artie Spivak could buy Milt’s instruments and his record cards. But he couldn’t buy what was in Milt’s brain, or in his hands. Just as well. The human mouth was only so complex. If Artie were able to inherit Milt’s knowledge, he would have nowhere to progress to.

Milt plucked the last wad of gauze from Geneva Sink’s cheek, which collapsed in a hollow way that frightened even Milt. “That ought to do it,” he said loudly, and clapped his hands, so she startled awake. He saw she couldn’t rise and offered her his arm.

“My advice to you, Milton Rothstein, is keep your mind active.”

He thought she was going to assign him extra math problems to do during his retirement, and he was going to tell her in sharp terms that he had no intention of doing them, but he heard in the waiting room the rustling of a commotion. The hairs on his neck pricked up.

“No, the doctor is with a patient. You can’t go in there.”

Geneva Sink, as if she too feared this visitor, untied her purse and handed Milt a check for the sum she’d earlier determined ought to cover whatever work he might do. She walked as quickly as she could past Olivia Golden and the dark shape she was wrestling.

“Ver vet zikh farnem mit mir! Blayb!” The man bellowed like a bull granted half-human speech. Milt understood what he said—Who will care for me! Stay!—only because he’d grown up with this bull.

“Loz op dos meydl!” Milt ordered. Leave the girl alone! And Sonny did as he was told—he charged Milt instead, grasped him around the shoulders and lay his shaggy head on Milt’s smock. The odors of urine, sardines, and Vitalis nearly gagged Milt. He thought the heavy body would pull him to the floor. “Genug!” he cried, Enough!, and he meant not only enough of Sonny’s carrying on, but enough of Milt repaying a debt he’d never owed. Were they related? No, they weren’t. Well, all right, there was some sort of shirt-tail connection between Milt’s grandfather and Sonny’s, back in Galicia. But mostly it was an accident of proximity—Sonny’s father’s farm up the road from Milt’s and Moose’s, those few days they’d all walked down the hill together to school. Before Sonny got his first seizures, Milt and Sonny resembled each other so much the second-grade teacher, Mrs. Mulhaus, asked in a puzzled way if the boys were brothers, as if Jews used this suffix, this “—stein,” to show they were secretly related. Then Sonny had that first horrible fit, thrashing in the row between his desk and Milt’s. The pencil Mrs. Mulhaus jammed between Sonny’s teeth snapped, and that was the last anyone at school saw of Sonny Kuppelstein. His mother was ashamed—she’d been bad-mouthing Sonny’s father for years, a stupid farmer shoveling cow shit, this was his fault too. The few times Milt went over there on an errand, he found Sonny in the barn, which was where Sonny went to have his fits—fifteen, sometimes twenty in one day—in the manure-sodden hay among the cows. Year by year Sonny grew more twisted, more distorted, so Milt thought of Sonny as some ill-fated shadow of himself; all the bad luck Milt should have gotten in the normal course of life was visited on Sonny. He’d been a handsome boy, but who could tell that now? If Hollywood wanted to make a Yiddish version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame, well, here was their star.

And then, modern miracle, a drug is invented that stops Sonny’s seizures. This isn’t progress, the hunchback leaves his barn and goes out in daylight? Too bad he can’t read, can’t make his own living—the mother should roast in Hell, to ruin a child’s life from her own shame. And the husband, giving in to her, though at least Mr. K. made sure Sonny should get a little check each month from the sale of the farm, on top of the disability, enough to pay Milt for the dental work he managed to do for Sonny. Because even miracles have side effects—the Dilantin swelled Sonny’s gums so bad the teeth dropped out, and the poor son of a bitch couldn’t sit still long enough to get fitted for dentures, Milt had to work on Sonny’s mouth practically running around the office, so the dentures never did sit right, they slipped out and cracked every few months.

Oh, Daddy, they have a name for people like you, his daughter Wendy told him. It’s a disease, thinking you have to take care of everyone. As if his daughter were the authority on taking care of people! She moved every six months—West Coast, East Coast, Ohio, Alabama, she thought it was a big sacrifice she had to take off a few days from the newspaper when Gretta had that lump removed. A lump in the breast, now that was a disease. It was not a disease you should take care of people. Okay, so maybe there was a little bargaining involved—I help him, You help me. But that made it a disease?

“Ikh vel nisht geyn!”

Sonny was still hanging on to Milt, pawing him, fat tears struggling along the crazy valleys and patchy stubble of Sonny’s cheeks, and all this so revolted Milt he found the strength to push Sonny off. That was the trouble with helping a person like Sonny. You reached a point where, it was only the truth, you wished him dead.

Sonny slumped against the wall and let his monstrous bulk slide to the floor. He sank his big face in his palms. “Ikh vel nisht geyn!”

“So stay!” Milt told him. “Only don’t make so much fuss!”

Sonny did as he was told, sobbed and rocked softly in the corner through all six of Milt’s morning appointments, none of whom seemed to notice, they were too busy chiding Milt: How could he desert them? How could they trust another man in their mouths? Milt grew angrier and angrier, his hands shaking so badly he dropped a scaler on the dirty floor, and when he picked it up it was all he could do to keep from jabbing it through Sonny Kuppelstein’s heart.

And then, mercifully, it was lunchtime, and he hadn’t stabbed anyone or even raised his voice. He thought of the bowl of tomato soup and the cheese sandwich and the glass of cold pineapple juice waiting on the kitchen table at home, imagined Gretta telling him about her ride to Roscoe that morning, how the doctor said it was nothing, she should only get another check-up next year. After lunch, Milt would lie down for a little nap, and Gretta would lie next to him, she’d be tired from her trip.

But when he called home to tell Gretta he was on the way, no answer. He let the phone ring, refiguring how long it would take Gretta to drive to Roscoe, be examined, maybe stop at the trout farm to pick up a little something for dinner. Maybe she’d turned off at the Beaverkill River to sketch the covered bridge?

This idea comforted him, for a moment. Then he grew so dizzy with the effort of thinking it up that he staggered like a knifed gangster back through his office, past Sonny Kuppelstein—a mound of moaning laundry—and slumped into the spare dental chair in the back room. He must have dropped off to sleep, because Milt dreamed something—he was working on himself, both patient and dentist, yelling at himself: You’re a shame to the profession!, until he jerked awake, hungry, still woozy, Olivia calling from the door to announce his one-thirty.

How could he go back to work? It was as if he’d been laboring with someone in his sleep, a man as large as Sonny—who, thank God, was gone now from his corner, though the shadowy threat of him was still there, like the X-ray shadows of those poor blasted Japanese, though at the time Milt was damn glad Truman dropped those bombs so Milt and Moose and the other G.I.s didn’t have to invade the islands.

He splashed his face, ran his wet fingers through his hair, and then he was all right, he worked the entire afternoon without anger. This is the last patient you’ll ever work on, he lectured himself, but he couldn’t convince himself to care. Only when he was settling the gridded tray of instruments back inside the steamy sterilizer, soaping his hands, unsnapping his smock, only then did he panic. Without these rituals, these ablutions, what would give his days structure? A mistake! All of it, a mistake! He’d thought he was cutting himself free of the net that entangled him, and it was the safety net he’d gotten rid of.

“Doctor?” Olivia looked in. “Oh, I’m sorry!” because she’d never seen him like this, in his undershirt. Olivia tried to wipe away her tears, but couldn’t, because she was still carrying that box. “Doctor, you’ve been very good to me, and to Hunkie, and if there’s anything I can ever. . . .”

Do for him? She, Olivia Golden, whose whole professional life could be contained in one cardboard box?

Olivia stepped forward to hug him, but the box was in her arms, which was just as well, Milt being in his undershirt. “Oh, Doctor, I hate to leave this way, so quick, but I can’t hold this box much longer. Good-bye, Doctor! Good-bye!”

When she was gone, Milt buttoned his shirt, went out to the bare desk and rummaged through the drawers. All he found was his appointment book. Pens. A few stamps. He opened the book to see who was coming in the next day, and the empty page startled him.

“Milt? Milt, you in there?”

His friend Moose stood by the coat rack, this man Milt had known for sixty-nine years and was now moving away from.

“Milt? You ready?”

Milt felt himself stumble forward from the shadows. He wrapped his arms around his friend. Moose stiffened. Then he returned Milt’s embrace.

“You goddamn son of a bitch,” Moose said, “it’s about time.”

“Moose, Moose, I never stopped to think . . . Why don’t you come with us? Give away the business. Do you need the aggravation? All those widows down there, a healthy guy like you. . . .”

“Ahh, widows, just what I need.” He pushed Milt back. “I’ll drive down for a visit. If it’s as good as you say, maybe I’ll unload the dairy, get what I can for the house. . . .”

But Milt knew his friend would never move. It was like some war movie, the guy whose hitch was up making plans to meet his buddy in New York, after the big battle, and the buddy never shows up.

They walked through Milt’s foyer, and Marv was suddenly following them, as if he’d been waiting, peeking out the door.

“You talk to that candyass kid yet? About the rent, and the papers?”

Milt didn’t bother with a reply. Marv asked for these impossible things only because he didn’t know how else to talk to his brother, the way some people never prayed to God except to ask for favors. Something else was on Milt’s mind. Had he unplugged everything? Locked the office door? Well, so what if he hadn’t. The thief would be stealing from Artie Spivak. Still, it was as if someone were following them. Milt looked back, expecting to see Sonny Kuppelstein lurching along the sidewalk, but Sonny wasn’t there.

Oh, who wanted to sit in that smoky restaurant eating fatty meat with a bunch of old farts? Let them give their award to the man who’d attended all those meetings in his place. Milt would be home with Gretta, who surely must be back from her appointment by now.

Fool, he thought suddenly. Fool! He stopped, there, in front of the post office. She’d been home all afternoon, only not answering.

Moose and Marv kept walking.

“I’ll see you later!” Milt cried out, and he started running up the hill, he didn’t even stop for his car, up and up through air the same butterscotch gold as those candies, past the maples with their quivering leaves. Lucky. Too lucky. Got away from the farm, made it through all that fighting, through dent school—thank the G.I. Bill for that. Then Gretta—you didn’t deserve her. A daughter, and a son, both married, with good jobs. He passed the boarding house, the light from Sonny’s window blue from the TV, and Milt saw in his imagination Yakob Kuppelstein, Sonny’s father, a big sloppy man, though a kind-hearted one, lowering his suspenders and unbuttoning his pants and walking glumly into the bedroom he shared with that yachne, Sonny’s mother, and Milt wondered if he had in fact ever seen Sonny’s father unbuttoning himself this way. Some boyhood glimpse? But how could Milt have known that Sonny’s mother would be waiting in that bed, yellow slip pulled grotesquely above her thighs, scolding her husband as if he’d already failed to please her? And why should Milt think of this now, for God’s sake?

Gasping, he hurried past the maple on his own lawn, the spot where Wendy’s cat, decades earlier, scratched the trunk, the claw marks now two feet long and as widely spread as if a sabertooth had raged there, and Milt felt as if that same sabertooth might be crouching behind his own front door.

Not a light inside, though Gretta’s keys were on the metal-and-glass table, beside a glossy pamphlet such as a doctor might give you to explain a diagnosis. Gretta herself was in the living room, staring out the back window, not the kitchen window in front, as she usually did; it was as if she’d chosen to look backward, at the past. She wore a dark dress, so the only luminous thing in the room was her neck. Long hair, he thought, no hair, and he slammed his fist on the glass tabletop, so Gretta screamed and jerked her head around, her face anguished and passionate, the face no one but Milt had ever seen. The silence was hissing at him already, and he muttered back, indistinctly, so maybe Gretta thought he was cursing her, “You son of a bitch! Couldn’t You have waited a little longer! All these good years, and now this?”

*

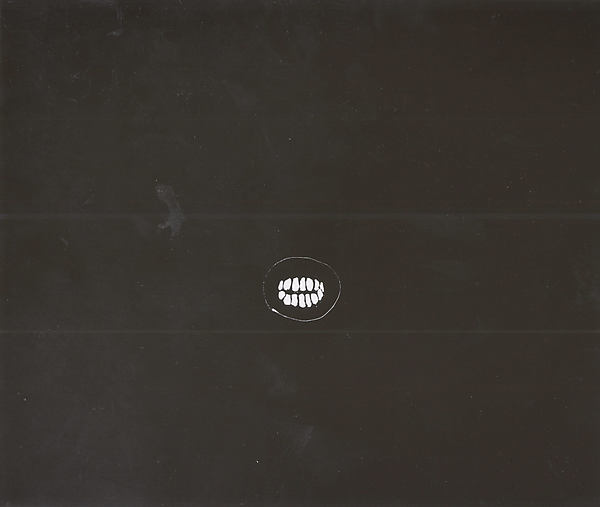

Image: Dine, Jim. “Teeth.” 1961. Gouache on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.