Nonfiction from Natalie Bakopoulos excerpted from our Summer 2016 issue.

*

…when I am another, my acts

are more mine when they are the acts

of others, in order to be I must be another,

leave myself, search for myself

in the others, the others that don’t exist

if I don’t exist, the others that give me

total existence, I am not, there is no I, we are always us.

from “Sunstone” by Octavio Paz

translated by Eliot Weinberger

On close inspection, all literature is probably a version of the apocalypse that seems to me rooted … on the fragile border … where identities (subject/object, etc.) do not exist or only barely so — double, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject.

from “Powers of Horror” by Julia Kristeva

1. Boundaries of knowledge

In the opening of Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child, the fourth book of the Italian writer’s Neapolitan novels, the narrator, Elena Greco, notes: “Now that I’m close to the most painful part of our story, I want to seek on the page a balance between her and me that in life I couldn’t find even between myself and me.” “Her” here refers to Lila Cerullo, as Elena calls her, and these four novels, arguably one large masterpiece, chronicle the lives of and friendship between these two women set against the backdrop of Italy’s charged sociopolitics. Elena’s desire for balance here is representative of the intricate balance and boundary between the self and the other that exists in these novels. Their friendship becomes a continual process of blurring what is imagined and what is real to achieve a sort of truth, a mutual constitution of self and other.

The friendship is both tender and antagonistic, deeply intimate and full of spite, and Elena reflects on the difficulty of telling her own story without Lila in it. There is Lila’s story and there is Elena’s story, but Elena realizes the two are inextricable. The “very nature of our relationship,” Elena notes, “dictates that I can reach [Lila] only by passing through myself.” Lila, however, is adamant that her own story is not interesting, but Elena cannot admit that she is right, nor can she admit that “as the years pass, the less [she knows] of Lila.” And, perhaps, the less she knows of herself.

Rachel Donadio, in her New York Review of Books review of Ferrante’s novels (published before The Story of a Lost Child was released in English) eloquently argues that these books are about knowledge: “What kind of knowledge does it take to get by in this world? How do we attain that knowledge? How does our knowledge change us and wound us and empower us … ? What things do we want to know and what would we prefer to leave unknown?”

It’s a smart, astute observation, to which I would add that these novels feel less about knowledge as a goal and more about its flux, how knowledge not only changes us but how we might have a role in creating that knowledge. New knowledge creates new possibilities, after all, fulfilling certain needs that were limited by its previous lack. This lack of knowledge, and of power, can work as a catalyst, and writing is a way to claim both: “I loved Lila,” Elena notes. “I wanted her to last. But I wanted it to be I who made her last.”

There are boundaries to knowledge, of course. Elena struggles with the fact that “as the years pass, the less [she knows] of Lila.” Knowledge isn’t always absolute, and truth, these novels suggest, isn’t either. The books are about being perpetually in between, about hovering near the borders, about becoming. The story of the complicated friendship explores the idea of boundaries and balance: of narration, of knowledge, of the body, and of the self. A friend is, as Aristotle would say, one’s other self.

So when Lila goes missing, at the age of sixty-six, Elena takes it as a personal affront and a personal loss. “It’s been at least three decades since [Lila] told me that she wanted to disappear without leaving a trace, and I’m the only one who knows what she means.” Her whereabouts — the novel’s great unknown, drives the novels forward, but the best suspense comes from what we know, not what we don’t. And we know Elena’s need to write it all down is hardly simply an act of memory or preservation. It’s one of spite, a continuation of a constant battle, and balance, between them; it is also one of desire. Elena muses:

How easy it is to tell the story of myself without Lila: time quiets down and the important facts slide along the thread of the years like suitcases on a conveyor belt at an airport: you pick them up, you put them on the page, and it’s done.

What she means is: without Lila, there isn’t much of a story, or much of herself.

And if in order to know Lila she must more aggressively pass through herself, the boundaries between these two women are blurred and porous. As Montaigne has said of friends: “souls are mingled and confounded in so universal a blending that they efface the seam which joins them together so that it cannot be found.”

…

To continue reading “We Are Always Us: The Boundaries of Elena Ferrante,” purchase MQR 55:3 (Summer 2016) for $7, or consider taking out a one-year subscription for just $25.

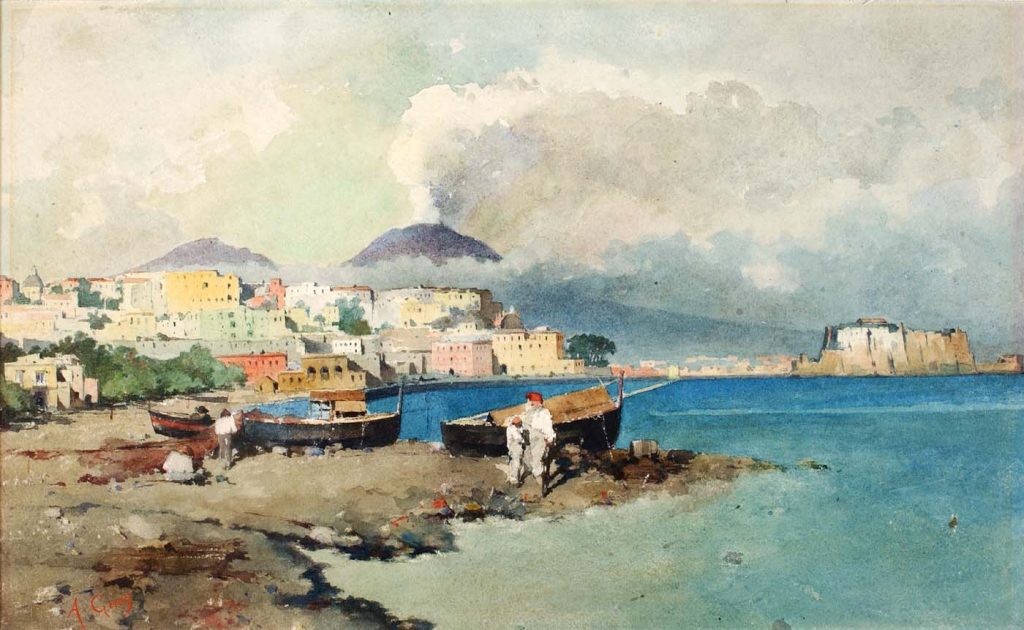

Image: Gurri, A. “Naples and Vesuvius.” 1930. Watercolor. The Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.