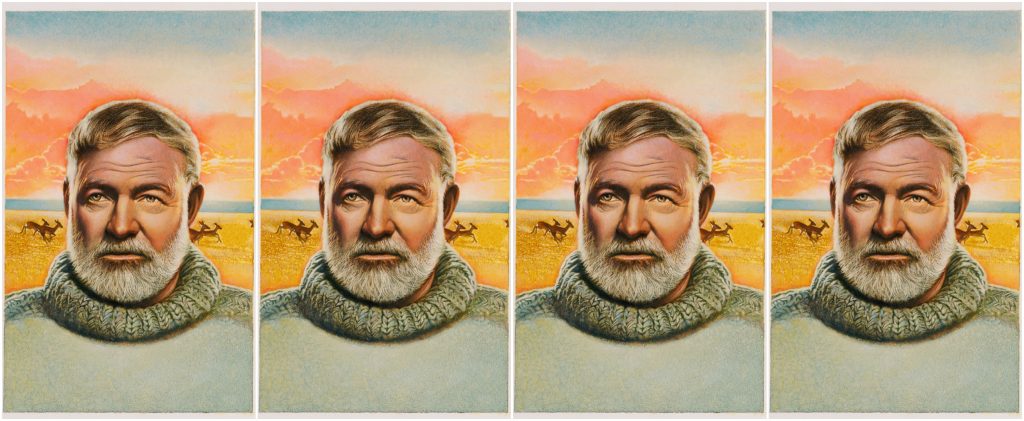

“Hemingway’s Humor,” nonfiction by Jeffrey Meyers, appeared in the Spring 2004 issue of MQR.

*

Hemingway’s fame rests on his tragic romances of love and death; his evocative stories crafted in spare prose; his vivid war reporting and travel books. He was not a comic writer, and when he tried to be funny he could be heavy-handed, as in his parody The Torrents of Spring, or embarrassingly arch, as in the tedious conversations with the Old Lady in the otherwise fascinating Death in the Afternoon. Yet his most underrated quality was his lively sense of humor. In his personal life he was hard on himself and on others; in letters he could be savagely funny and satiric, contemptuous and malicious, even nasty. He liked elaborate, excessive insults and coined some colorful phrases. In his writing his wit could be charming and tender, mordant and cynical, his humor sly and clever. In the most serious contexts, flashes of amusement relieve the tension of the drama or cast realistic light on a romantic situation.

John Dos Passos once remarked that “Hem was the only man I ever knew who really hated his mother.” She was the focus of his youthful resentment as well as his bitter humor about women. In 1918, in New York and about to work for the Red Cross in Italy, the teen-aged Hemingway rebelled against her puritanism and propriety. As a practical joke, he announced his “engagement” to the film star Mae Marsh, whom he’d never met. His parents failed to get the joke, and his father wrote to complain that it “had taken five nights sleep from your mother . . . who was broken hearted.” Finally, Hemingway had to explain that it was all pure fantasy. While living in decadent Paris after the war, matured by his experience, married and embarked on his career, he adopted a more sophisticated tone. Using one of Grace Hemingway’s favorite clichés, he told his father that she had an overdeveloped sense of sin: “I remember Mother saying once that she would rather see me in my grave than something — I forget what — smoking cigarettes perhaps.”

Later on he blamed his mother for his father’s suicide, and portrayed Ed as a castrated weakling, dominated by the monstrous Grace. In what was surely a ludicrous exaggeration, he told his fourth wife, Mary, that Grace “never forgave me for not getting killed in World War One, so she could be a Gold Star Mother.” On another occasion, opposing a conventional with a contemptuous response, he dramatically exclaimed: “Jesus, is it Mother’s Day? Then I’ll have to send the old bitch a wire.”

Despite his crude talk in speech and letters, Hemingway was sensitive and vulnerable. He had a corresponding impulse to retaliate for slights, to hit out against family, wives, friends and literary rivals. This defensive urge provoked his comic and grotesque put-downs. Enraged at his older sister, Marcelline, for criticizing his divorce from his first wife, Hadley, he compared his sister to a coffin and called her “a bitch complete with handles.” His younger brother, Leicester, who feebly imitated Hemingway and tried to cash in on his reputation, portrayed him as the swaggering Rando Granham in his autobiographical novel The Sound of the Trumpet. Hemingway called it “a chickenshit abortion filled with the worst crap I have ever read. The few good parts were like ripe plums in vomit.”

Hemingway was deeply romantic about women. His serial loves and marriages were essential to his emotional life and inspired his work. But when these relationships disintegrated he adopted an aggressive posture and shot off witty remarks or retaliatory barbs. When living with his second wife, Pauline, in Key West in the 1930s, he had a mistress, Jane Mason, in Havana. Beautiful but emotionally unstable, Jane jumped out of a window in her house and broke her back. Hemingway, detaching himself from the disaster, portrayed himself as the indifferent male and called her “the girl who fell for him literally.” When he finally asked Pauline for a divorce, she vindictively said: “Ernest, if you divorce me I’ll take everything you’ve got,” and he replied: “Pauline, if you let me have a divorce, you can have everything I’ve got.” He felt it would be worth everything he had to get rid of her — though much of what he had, his house and boat (and African safari), had been paid for by her generous rich uncle Gus. But the facts were less important than getting back at his wife and making himself the victim.

His third wife Martha, his most engaging victim and the only woman who left him, admitted that Hemingway could always make her laugh, even when she wanted to murder him. Martha had a mania for cleanliness and called Hemingway (none too fondly) “The Pig.” He complained to Aaron Hotchner that “her father was a doctor, so she made our house look as much like a hospital as possible.” As their marriage began to disintegrate, right after it began, he became increasingly critical. Using a racing metaphor for that thoroughbred, he remarked that she “had but three gaits” — two fast, one slow — “running away, over-work, and sleep.” He claimed that Martha, who’d attended Bryn Mawr and rivaled him as a foreign correspondent, “had made more money writing about atrocities than any woman since Harriet Beecher Stowe.” When she took off to report the Russo-Finnish War in 1940, Hemingway, in a joke tinged with self-pity, portrayed himself in tropical Cuba as a tribesman who needed female warmth in his teepee: “What old Indian likes to lose his squaw with a hard winter coming on?” Fearing Martha’s independence would lead to infidelity, he also insisted: “I need my wife in bed and not in the most widely circulated magazines.”

After their divorce Hemingway, suggesting that most upper-class women had sexual difficulties, told Bernard Berenson that Martha “was not built for bed but few nice people are.” Her narrow vagina made her sexually unresponsive, but after she had a vaginoplasty, an operation to widen her parts, their sex life improved. It was like entering a cathedral, he exclaimed, “like coming into Penn Station.” After their marriage collapsed, Hemingway called one of his cats Mooky, a nickname she hated, and told his publisher Charles Scribner: “Have a new house-maid named Martha and certainly is a pleasure to give her orders.”

Ever the romantic, Hemingway overflowed with sentimental endearments while courting his fourth wife, Mary, whom he met in wartime London. But after they were married he soon began to resent her, and when she had an accident he was more annoyed than sympathetic. As with Martha, he compared Mary to a horse and reported that she had broken “her near hind leg.” When she became jealous of the young Italian Adriana Ivancich (the model for Renata in Across the River and into the Trees), he blamed Mary for his own dangerous flirtation, compared her to the sadistic Spanish Inquisitor-General and told her: “You have the face of a Torquemada.”

Proud and touchy, Hemingway had a hair-trigger temper and got even angrier as he got older. As early as 1922, as a young foreign correspondent, he was enraged when the International News Service questioned his travel expenses and sent them a terse telegram in cablese: “SUGGEST YOU UPSTICK BOOKS ASSWARDS.” All Hemingway’s friends agreed that he could be fierce when crossed. His driver, Toby Bruce, said: “he could be as mean as a striped-ass ape”; the photographer Robert Capa stated: “Papa can be more severe than God on a rough day when the whole human race is misbehaving”; and General Buck Lanham insisted: “when Hemingway was nasty he qualified as The King of All Nasties.”

Hemingway used letters to let off steam, retaliate against enemies, and express what couldn’t be printed. He used his cruel wit to pay off old grudges, elaborating his abuse and enjoying his own nastiness. In a letter of 1948, unhappy about the Belgians’role in the war and the crude postwar Belgian tourists, he described their distinctive repulsiveness in terms of offensive odors: “Been trying to think of what a Belgian smells like. . . . It is a blend of traitorous King, toe-jam, un-washed navels, old bicycle saddles, (sweated), paving stones. . . with a touch of leek soup and cooking parsnips.” Hemingway had always felt that writing was a rather unmanly profession and cultivated a compensatory tough persona. If writers were suspect, critics were much worse. He hated the critics, who turned against him in the early 1930s, as much as the Belgians, and referred to them in letters as “the eunuchs of art” and “the lice who crawl on literature.”

Aware of and perhaps even embarrassed by his role as a rich and successful author who needed dependents to sustain his way of life, Hemingway made many mordant wisecracks about parasites and followers. Punning on the title of Richard Llewellyn’s Welsh coal-mining novel, he remarked of a new manservant: “how green was my valet.” He defined the roles of the hard-drinking, down-home Toby Bruce as “secretary, treasurer, chauffeur, valet, and procurer.” His unfortunately named German translator “may have made errors but was always Horschitz.” Though unaware that his lawyer Alfred Rice was swindling him by taking a 30% (instead of the usual 10%) commission, Hemingway stressed his incompetence by grotesquely calling him “the reserve outfielder on my paraplegic baseball team.” In Cuba, when the Basque priest Father Andrés — who drank, cursed, and refused to behave like a priest — arrived at the Finca smelling like a billy goat, Hemingway would order the maid to launder his habit and remove his sweaty “odor of sanctity.”

Even friends did not escape censure. Though Hemingway admired Gary Cooper’s portrayal of Robert Jordan in For Whom the Bell Tolls and valued him as a sporting companion, he felt the rich but tight-fisted Cooper loved money more than most people loved God. He was critical about Cooper’s late conversion to Catholicism to please his wife (perhaps because he’d done the same thing when he married Pauline), and told a friend that Cooper now had both money and God.

Literary rivals came in for the same colorful rejection as wives. In a bilious letter of 1951 to Charles Scribner, Hemingway blasted the firm’s leading editor and authors. Max Perkins had “an idiot wife,” Thomas Wolfe was “a glandular giant with the brains and guts of three mice,” Scott Fitzgerald was “a dishonest and easily frightened angel.” The following year, when he saw the stage version of The Great Gatsby in New York, he said “he paid to get in and would gladly have paid to get out.”

His intense rivalry with Fitzgerald began with their first meeting in Paris in April 1925, when Fitzgerald had just published The Great Gatsby and Hemingway was still unknown. Fitzgerald introduced him to Perkins and to Scribners, which became his lifelong publishers. But helping Hemingway was always dangerous. As early as July 1925 he wrote to Fitzgerald, mildly mocking his intellectual limitations (though he’d been to Princeton and Hemingway had not gone to college), his snobbery, his alcoholism, and his unwarranted devotion to the destructive Zelda. He gave a brilliant satiric sketch of Fitzgerald’s self-indulgent life, so different from his own: “I wonder what your idea of heaven would be — A beautiful vacuum filled with wealthy monogamists, all powerful and members of the best families, all drinking themselves to death.”

Hemingway sometimes attacked other writers as a way of staking out his own territory. He felt his early experience in battle enabled him to distinguish between authentic and phony writing about war and death. Combining a business metaphor with military slang in a letter to the critic Malcolm Cowley, Hemingway attacked Archibald MacLeish for the unjust appropriation of public grief, for whoring at Fortune magazine, and for exploiting his brother’s death in leaden poetry: “Does Archie still write anything except Patriotic? I read some awfully lifeless lines to a Dead Soldier by him. . . . I thought good old Allen Tate could write the lifeless-est lines to Dead Soldiers ever read but Archie is going good. His brother Kenny was killed in the last war flying and I always felt Archie felt that sort of gave him a controlling interest in all deads.”

Hemingway, boasting in childhood that he was “‘fraid of nothing,” always took great risks. But fearful that he might die violently, he superstitiously joked about death. After the Great War he wrote that my “living grandfather, not the dead one, he’s dead, toted me to luncheon.” In Paris he said of the editor Ernest Walsh, stricken by tuberculosis and marked for an early death, “now that he is dying is getting to be a pretty nice guy.” Charles Fenton, author of an intrusive book on Hemingway’s literary apprenticeship, “set a bad example to other biographers by jumping to his death from a hotel window.” Making a witty remark out of the obvious, Hemingway was fond of observing: “Men are dying this year who have never died before.” When Tennessee Williams, who’d known Pauline in Key West, asked about her death, Hemingway rudely crushed him with: “She died like everyone else . . . and after that she was dead.” Recovering from the war in 1918, he claimed that being wounded and surviving was “the next best thing to getting killed and reading your own obituaries.” Thirty-six years later, after his second African plane crash, he did read his obituaries and maintained: “I could never have written them nearly as well myself.”

II

In the 1920s Hemingway displayed his wit in a range of literary work. He wrote verse parodies and his burlesque novel The Torrents of Spring. He blended reportage and mocking satire in the vignettes of In Our Time, wrote sophisticated, romantic, and cynical comic dialogue in The Sun Also Rises and black comedy in “The Killers.” Even his serious stories of love and death are streaked with wit. Humor lightened the tragic element in his minor works: Death in the Afternoon, Green Hills of Africa, To Have and Have Not and Across the River and into the Trees. He particularly mocked his favorite targets: Martha Gellhorn in a play and a story, and Scott Fitzgerald in A Moveable Feast.

Hemingway’s parody of Pound’s “Hugh Selwyn Mauberley” (“The age demanded an image / Of its accelerated grimace”) in “The Age Demanded,” written a few years after the Great War, expressed the prevailing anti-war sentiment of the time in a rudely obscene rejection of his parents’ prewar values:

The age demanded that we dance

and jammed us into iron pants.

And in the end the age was handed

the sort of shit that it demanded.

In a swipe against his religious upbringing he parodied the famous Twenty-third Psalm, “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not / want him for long,” in his mocking, pretentiously titled “Neothomist Poem.” Similarly, in the deliberately provocative story “Today is Friday,” he described two Roman soldiers casually commenting on the crucifixion as if Christ were a prizefighter in a boxing match:

“He was pretty good in there today.”

“Why didn’t he come down off the cross?”

“He didn’t want to come down off the cross. That’s not his play.”

In another early poem, “The Earnest Liberal’s Lament,” he punned on his own much-disliked first name and cynically mocked attempts to change the world:

I know monks masturbate at night,

That pet cats screw,

That some girls bite,

And yet

What can I do

To set things right?

In The Torrents of Spring Hemingway jeered at Sherwood Anderson’s fashionable but often absurd racial and sexual primitivism and set his story in northern Michigan. The Indian Red Dog, trying to identify Yogi Johnson’s origins, comically abbreviates the Indian names: “‘Your tribe. What are you—Sac and Fox? Jibway? Cree, I imagine.’ ‘Oh,’ said Yogi. ‘My parents came from Sweden.’ ” Parodying his own fondness for the word “commence” as well as Anderson’s style, Hemingway solemnly noted that “spring had not yet come, and the men who had commenced their orgies were halted by the chill in the air.”

In the Red Cross and as a journalist the young Hemingway had witnessed war in Italy, Greece, and Turkey. He knew the suffering of common soldiers and refugees, and always took a dim view of politicians and generals. Reporting the Genoa Economic Conference for the Toronto Star in 1922, he wrote that the Soviet Foreign Minister Georgi Chicherin was obsessed by his gaudy uniform, his deputy Maxim Litvinov had a ham-like face, and the German Chancellor Karl Wirth looked like the tuba player in a Bavarian band. Interviewing Mussolini just after he seized power that year, Hemingway immediately saw through the Duce’s theatrical mask and wrote: “there is something wrong, even histrionically, with a man who wears white spats with a black shirt.” He called him “the biggest bluff in Europe,” and concluded “you will see the weakness in his mouth which forces him to scowl the famous Mussolini scowl.”

In In Our Time Hemingway found a way to combine objective and imaginative writing, to express the range of powerful feelings he’d experienced in war. “L’Envoi,” the last vignette, balances brutal descriptions of the Greco-Turkish War with a satirical portrait of King George II of Greece. He used indirect speech, a playfully ironic tone, and the language of nursery rhyme: “The king was working in the garden. . . . This is the queen, he said. She was clipping a rose bush. . . . Plastiras is a very good man I believe, he said, but frightfully difficult. I think he did right though shooting those chaps. . . . Of course the great thing in this sort of affair is not to be shot oneself!. . . Like all Greeks he wanted to go to America.” The queen, clipping a rose bush like any suburban housewife, is utterly conventional; the king, under house arrest, rather petulantly complains of his restriction to the grounds of the palace. He cynically believes in the importance of survival, but has only four months left to rule. He would soon be deposed by General Nicholas Plastiras, who’d executed six ministers after the revolution of 1922 but whom King George calls “a very good man.” Despite his taste for whiskey and soda and for British diction (“frightfully,” “chaps”), the insecure and unhappy king is democratically reduced to the level of the immigrant peasant who dreams of opening a diner in America.

Hemingway’s return to Oak Park after his war wound became an important theme in his stories, and he used humorous irony to reveal the contrast between the cynical young man and his conventional family. In “The Last Good Country” he indirectly alluded to his mother’s dislike of his writing when the young Nick Adams responds with mock-solemnity to his sister’s objection:

“But St. Nicholas is our favorite magazine.”

“I know,” said Nick. “But I’m too morbid for it already. And I’m not even grown-up.”

In “Soldier’s Home” the mother exerts pressure on her traumatized son to start work, which he doesn’t want to do, and uses the language of religion, which he’s rejected. Numbed and embittered, Krebs unintentionally wounds his mother. She resorts to emotional blackmail and creates a scene that makes her stifling maternal love more difficult to bear than her hostility: “‘Don’t you love your mother, dear boy?’. . . ‘I don’t love anybody,’ Krebs said. . . . ‘I’m your mother,’ she said, ‘I held you next to my heart when you were a tiny baby.’ Krebs felt sick and vaguely nauseated.” The contrast between her demands and his response is painfully ludicrous.

Witty dialogue established both the cynical views of the expatriate characters and the disillusioned tone of The Sun Also Rises. Speaking of an exhausted hack-writer based on the once-renowned Joseph Hergesheimer, a character maintains: “He’s through now. . . . He’s written about all the things he knows, and now he’s on all the things he doesn’t know.” When Bill Gorton asks the once affluent Campbell, “how did you go bankrupt?,” Mike replies: “Two ways. . . . Gradually and then suddenly.”

Jake Barnes, alluding to a prostitute’s mind rather than her body (which his war wound prevents him from using), remarks: “It was a long time since I had dined with a poule, and I had forgotten how dull it could be.” By contrast, the woman he loves, Brett Ashley, a reckless English aristocrat down on her luck, is exciting but unreliable. When she fails to show up for a rendezvous at an elegant hotel, Jake stoically if sentimentally consoles himself. He observes that Brett is never there when he needs her, though he’s always there for her, “so I sat down and wrote some letters. They were not very good letters but I hoped their being on Crillon stationery would help them.” Hemingway often translated Spanish into English literally, and reproduced the formality of Spanish in comical English. At the end of the novel Jake answers Brett’s desperate summons to the Hotel Montana in Madrid. The manager insists that “the personages of this establishment were rigidly selectioned.” But Jake sceptically responds: “I was happy to hear it. Nevertheless I would welcome the upbringal of my bags.”

Brett, a breathtakingly outrageous woman, provides much of the novel’s wit. Though she loves Jake, she has affairs with the alcoholic Mike Campbell, the Princetonian Robert Cohn, and the bullfighter Pedro Romero. Referring to a louche hotel that rented rooms by the hour for sex, Brett crassly tells Jake that they asked her and Mike “if we wanted a room for the afternoon only. Seemed frightfully pleased we were going to stay all night.” In this voyeuristic novel (with a hero who cannot have sex), the characters look lustfully at each other. When Jake sees the Jewish Cohn staring longingly at the seductive Brett, he mock-heroically compares him to Moses after forty years in the wilderness: “He looked a great deal as his compatriot must have looked when he saw the promised land.” Admiring Romero in his sparkling, tight-fitting traje de luces, Brett suggests her interest in seeing him naked as well as dressed: “how I would love to see him get into those clothes. He must use a shoe horn.”

Death, an ever-present theme in Hemingway, could be the occasion of black comedy. The murderers in “The Killers” — who wear natty clothes, use mock-polite diction, and incongruously appear in a small-town diner — are compared to a cocky vaudeville team. One of them “wore a derby hat and a black overcoat buttoned across the chest. His face was small and white and he had tight lips. He wore a silk muffler and gloves.” His coat is as tight as his lips because he’s trying to hide a shotgun underneath it. Awaiting the arrival of their fatally resigned victim, the hitmen entertain themselves by intimidating the men in the diner with laconic insults that require immediate assent.

“You’re a pretty bright boy, aren’t you?”

“Sure,” said George.

“Well, you’re not,” said the other little man. “Is he, Al?”

“He’s dumb,” said Al. . . .

Both men ate with their gloves on.

Hemingway based “The Killers” on the comical-sinister gangsters of Al Capone’s Chicago. The sharp cinematic scenes and the wisecracking dialogue, contrasting the banality of the characters with the violent conclusion, influenced the portrayal of underworld characters in the films of Bogart, Cagney, and Edward G. Robinson.

Though the focus of Death in the Afternoon is the balletic ritual of death in the bullfight, Hemingway leavened the subject with amusing passages that place the corrida in the context of Spanish culture. Speaking of Madrid (where both inhabitants and visitors often dine at midnight and always stay up late) but remembering his days as a war reporter in the early 1920s, he noted: “in no other town that I have ever lived in, except Constantinople during the period of the Allied occupation, is there less going to bed for sleeping purposes.” He liked to joke, half-seriously, about the debilitating exactions of women, and said that retired matadors sometimes came back to fight “because the intensity of their domestic relations has relaxed.”

Hemingway made strenuous efforts to break from his Victorian past, but always retained an element of Midwestern puritanism. His glossary provided definitions that revealed his amused fascination with sexual commerce. He broadly explained puta as “whore, harlot, jade, broad, chippy, tart or prostitute,” adding of hijo de puta (son of a whore): “In Spanish they insult most fully when speaking or wishing ill of the parents rather than of the person directly.” Homosexuality, which repelled as it fascinated, was always an absurd sort of joke to him. Referring to the flourishes of a style inappropriate to the strict rules of the corrida, he defined maricF3n(a derisive word for homosexual) as “a sort of exterior decorator of bullfighting.” Speaking of Jean Cocteau’s lover Raymond Radiguet in the text, the narrator punningly explains: “He was a young French writer who knew how to make his career not only with his pen but with his pencil if you follow me.” He then quotes Cocteau’s ironic comment on Radiguet: “Bebé est vicieuse — il aime les femmes.” Hemingway used the feminine form of the word for “vicious” (instead of vicieux) to suggest that Cocteau was speaking as if his lover were a woman.

Hemingway also used the glossary to describe, with comic exaggeration, one of the dangers of foreign travel, which he called “heel rape”: “ambulatory venders will come up to you while you are seated in the café, [and] cut the heel off your shoe with a sort of instant-acting leather-cutting pincers they carry, in order to force you to put on a rubber heel.” Hinting at a milder form of crucifixion, he suggested an absurd solution to the problem. The best thing to do when you see one of them approaching “is to take off your shoes and put them inside your shirt. If he then attempts to attach rubber heels to your bare feet, send for the American or British Consul.” Speaking of pickpockets in his gloss on maleante (corrupter), Hemingway remarked that “in their own walk of life these gentry combine the same qualities that Montés listed as indispensable to a bullfighter — lightness, valor, and a perfect knowledge of their profession.”

In a letter to Gertrude Stein, who first told him about the bullfights in Spain, Hemingway delighted in the grisly aftermath of the corrida, and liked to imagine how the experience would shock the folks back home. The triumphant matador, awarded an ear, had honored Hemingway’s wife with his bloody trophy: “Hadley got the ear given to her and wrapped it up in a handkerchief which, thank God, was Don Stewart’s. I tell her she ought to throw it away or cut it up into pieces and send them in letters to her friends in St. Louis but she won’t let it go and it is doing very nicely.” (Stein later told Hemingway: “anyone who’s married three girls from St. Louis hasn’t learned much.”) Describing the horrid ear as if it were a newborn infant, he added, with “thank God,” just the right touch to this delightful vignette.

Hemingway saw both humor and anguish in sex, a subject which provoked a great many wisecracks and witticisms. Nick Adams has a series of sexual intimations and experiences. In “Fathers and Sons,” his father challenges the young Nick for using an improper word:

“The little bugger,” Nick said.

“Do you know what a bugger is?” his father asked him.

“We call anything a bugger,” Nick said.

“A bugger is a man who has intercourse with animals.”

“Why?” Nick said.

“I don’t know,” his father said. “But it is a heinous crime.”

Though he objects to Nick’s use of the word, the father provides a deliberately incomplete definition of “bugger.” He avoids discussing sodomy between humans and talks instead of the far less common bestiality, which he doesn’t understand. To disguise his meaning he uses the word “heinous,” which Nick doesn’t understand. His intervention exposes his own prudery and leaves Nick confused. This funny and sad conversation shows how fathers want both to hide and to explain the truth about sex, and how sons have to pick up as much of the puzzle as they can.

Nick’s sexual initiation continues when his Indian friend Billy asks him if he wants to go another round with his sister Trudy. (Like her real life model Prudy Boulton, she “did first what no one has ever done better”):

“You want Trudy again?”

“You want to?”

“Un Huh.”

“Come on.”

“No, here.”

“But Billy—”

“I no mind Billy. He my brother.”

When Nick asks Trudy the same question that Billy asked him, she apparently assents with an inarticulate “Un Huh.” Though Billy drops out of the conversation during their next exchange, he remains a formidable presence. Nick doesn’t understand Indian sexual customs or Billy’s attempt at male bonding. But he realizes through her casual non sequitur (“He my brother”) that she doesn’t mind doing it again while Billy’s watching. (In “Summer People” an older Nick Adams jokes about the sexual promiscuity of the lower classes when he asks: “Why weren’t there any virgins in state universities?”)

“Fathers and Sons” connects Nick’s sexual experience with memories of his father’s death. In his description of how the cosmetic mortician reconstructed his father’s gun-shattered face, Hemingway wittily contrasted the undertaker’s complacency with his dubious repairs: “The undertaker had been both proud and smugly pleased. But it was not the undertaker that had given him that last face. The undertaker had only made certain dashingly executed repairs of doubtful artistic merit. The face had been making itself and being made [by his father’s sad life] for a long time.” Hemingway found a wry irony indispensable when writing about the most agonizing experiences of his life.

In the Foreword to Green Hills of Africa, about hunting big game on his first safari, Hemingway joked about the essential requirement of popular books: “Anyone not finding sufficient love interest is at liberty, while reading it, to insert whatever love interest he or she may have at the time.” His work in fact is full of “love interest” and he wrote about all the women he loved. He idealized the women in A Farewell to Arms and Across the River and into the Trees, but his wives were usually satiric targets. The perfect tone and petulant repetition of “Cat in the Rain” captured the character of the childish American wife, based on Hadley — spoiled, demanding, and irrational: “‘Anyway, I want a cat,’ she said. ‘I want a cat. I want a cat now. If I can’t have long hair or any fun, I can have a cat.'” (Hemingway’s ear for dialogue was especially accurate in this story. In a letter of May 1915, Katherine Mansfield said something very similar: “Why haven’t I got a Chinese nurse with green trousers and two babies who rush at me and clasp my knees — I’m not a girl — I’m a woman. I want things. Shall I ever have them?”) In his African book Hemingway gently punctured the vanity and fantasies of his petite, small-boned wife Pauline. She “disliked intensely being compared to a little terrier. If she must be like any dog, and she did not wish to be, she would prefer a wolfhound, something lean, racy, long-legged and ornamental.”

To Have and Have Not, set in Havana and partly based on his affair with Jane Mason, describes a voyeuristic intrusion and a farcical coitus interruptus. Tommy Bradley opens the door of the bedroom and observes his wife Helène and the writer Richard Gordon making love in his house. As the distracted Gordon sees Bradley and squirms with discomfort, Helène exclaims: “Don’t stop. . . . Please don’t stop. . . . Don’t mind him. Don’t mind anything. Don’t you see you can’t stop now? . . . That’s only Tommy. . . . He knows all about these things. Don’t mind him. Come on, darling. Please do.” Gordon is unable to continue but Helène assumes they can carry on as if nothing has happened. She angrily asks: “My God, don’t you know anything? Haven’t you any regard for a woman?” Attacking the predatory, sexually demanding woman after both Tommy and Richard have tactfully withdrawn, Hemingway emphasizes the habitual offender’s crass dismissal of her husband: “That’s only Tommy. . . . He knows all about these things.”

Martha Gellhorn was a frequent target of Hemingway’s cruel wit. While they were still married he satirized her as Dorothy Bridges in his play, The Fifth Column. The hero Philip Rawlings wants to marry Dorothy but disapproves of her luxurious tastes, and his friend warns her: “Don’t be a bored Vassar bitch.” Infatuated with her but aware of her flaws, Rawlings calls her “lazy and spoiled, and rather stupid, and enormously on the make.” Apparently clairvoyant about their troubled future, Hemingway has Rawlings explain: “I’m afraid that’s the whole trouble. I want to make an absolutely colossal mistake.” In his postwar story “It Was Very Cold in England,” the Hemingway character has an acerbic exchange with an unnamed woman based on Martha. As they stir up their old rivalry as war correspondents, he hints at her infidelity. Then, using a sexual pun and describing their tempestuous marriage in terms of war, he compares her to a dud mine that fails to detonate when properly rammed: “You remind me of the old, badly laid mines . . . that wash up years afterwards along the coast after the big fall and winter storms.”

For Whom the Bell Tolls marked a return to the idealistic love of A Farewell to Arms. The young Maria, who’s been raped by the Fascists, retains her innocence and Robert Jordan treats her like a virgin. The first time they kiss and make love, in a lyrical interlude between her violation and his death, she asks, in a famous and charming line: “Where do the noses go? I always wondered where the noses would go” (the use of “would” is masterly). In contrast to Maria, Hemingway created the earthy, sharp-tongued Pilar, the quintessential Spaniard, the gypsy and past mistress of bullfighters, the sexual expert and dominant female. Giving a new spin to regional fruit, she maintains: “The melon of Castile is for self abuse. The melon of Valencia for eating.” And she quickly demolishes her boastful, alcoholic, and finally submissive husband Pablo:

“In those days I was very barbarous.”

“And now you are drunk,” Pilar said.

“Yes,” Pablo said. “With your permission.”

“I liked you better when you were barbarous.”

Hemingway described Colonel Cantwell’s romance with the young Italian girl in Across the River and into the Trees in an arch and often irritating tone, but balanced the love affair with the hero’s bitter gibes and reflections on war. A Milanese war profiteer “accused his young wife . . . of having deprived him of his judgment through her extraordinary sexual demands.” In a grisly pun on “impression,” Cantwell’s driver (who pronounces “vehicles” with a long “i”) warns him: “Sir, there is a dead GI in the middle of the road up ahead, and every time any vehicle goes through they have to run over him, and I’m afraid it is making a bad impression on the troops.” In another grotesque incident Cantwell, combining the rational with the absurd in a solemn ritual, uses geometry to blot out the effects of his youthful battle trauma on the Italian front. Squatting on the bank of a river, he “relieved himself in the exact place where he had determined, by triangulation, that he had been badly wounded thirty years before.”

Quoting a popular line from The Merchant of Venice, Cantwell asks: “what’s the news from the Rialto now?” The waiter at his favorite bar, alluding to the backbiting gossip in Venice, replies: “You will get it all at Harry’s except the part you figure in.” Hemingway, quite good at backbiting, particularly disliked the overly cautious Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. In the novel Cantwell asks for “Two very dry Martinis . . . Montgomerys. Fifteen to one.” This punning order alludes not only to the extreme proportion of gin to vermouth in the martini (also the name of a rifle) and to Monty’s campaigns in the dry North African desert, but also to the commander’s need for overwhelming superiority before he would risk confrontation with the enemy.

In his later works Hemingway does not always achieve the fine balance of light humor and tragic defeat that stamps his greatest work. Instead, he aggressively used his fiction to retaliate against rivals and enemies. In Across the River he unleashed his most devastating vitriol on Sinclair Lewis who, like Faulkner and Hemingway, was an alcoholic and, after winning the Nobel Prize in 1930, had gone into a sharp decline. His attack on Lewis — so unsympathetic, extreme, and unnerving — has an element of repulsive wit. Readers who recognized Lewis as the unnamed American spotted by Cantwell at a nearby table in Harry’s Bar, would probably have known that Lewis suffered from skin cancer that had to be burned off every few months by cobalt treatments and that his raw red skin had horrible pock marks coated with pus. Emphasizing his physical revulsion, as he did with Ford Madox Ford and Wyndham Lewis in A Moveable Feast, Hemingway described Sinclair Lewis’s ferret features, ghastly craters “and black hair that seemed to have no connection with the human race. The man looked as though he had been scalped and then the hair replaced. . . . He looks like a caricature of an American who has been run one half way through a meat chopper and then been boiled, slightly, in oil.”

Hemingway’s attacks on Fitzgerald, though not quite as nasty, had a devastating effect on Scott’s character and reputation. In Torrents of Spring he good-naturedly alluded to Fitzgerald’s irritating habit of dropping in unannounced in Paris and getting self-destructively drunk: “Fitzgerald came to our home one afternoon, and after remaining for quite a while suddenly sat down in the fireplace and would not (or was it could not, reader?) get up and let the fire burn something else.”

By 1936 Fitzgerald, like Sinclair Lewis, had become for Hemingway a frightening example of a writer who’d betrayed his talent and been destroyed by popular success. The hostile reference to Fitzgerald in the Esquire version of “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” originated with the Irish writer Mary Colum, who’d put down Hemingway with a witty remark. He avenged himself by appropriating her comment and by victimizing Fitzgerald, who’d just revealed his disastrous personal life in “The Crack-Up” and was particularly vulnerable: “he remembered poor Scott Fitzgerald and his romantic awe of [the rich] and how he started a story once that began, ‘The very rich are different from you and me.’ And how some one had said to Scott, Yes, they have more money.” That same year, stressing Fitzgerald’s permanent immaturity, Hemingway told Max Perkins that “it was a terrible thing for him to love youth so much that he jumped straight from youth to senility without going through manhood.”A decade after Fitzgerald’s premature death, he told Scott’s future biographer that, derailed by Zelda, he’d suffered a sharp decline: “He had a very steep trajectory and was almost like a guided missile with no one guiding him.”

Despite Hemingway’s almost affectionate account of their ludicrous, rain-soaked trip from Lyon back to Paris in a small Renault whose top Zelda had willfully removed, his man-of-the-world indictment in A Moveable Feast was even more crushing. Long before they set out for Lyon, Hemingway rather cryptically noted that Fitzgerald’s “delicate long-lipped Irish mouth . . . worried you until you knew him and then it worried you more” — when you realized the weakness it revealed. Fitzgerald drank Mâcon wine from the bottle while they were traveling in the car and “it was exciting to him as though he were slumming or as a girl might be excited by going swimming for the first time without a bathing suit.”

The comical high point of the trip occurs in their hotel room in Lyon. Fitzgerald, with a low fever, lies on his bed looking “like a little dead crusader.” Hemingway, his attendant and nursemaid, says with deadpan humor: “I was getting tired of the literary life.” Charging Hemingway with callous indifference, Fitzgerald exclaims: “You can sit there and read that dirty French rag of a paper and it doesn’t mean a thing to you that I am dying.” He insists that his temperature be taken and Hemingway, having acquired a large thermometer designed to test bathwater, shakes it down professionally and warns him: “You’re lucky it’s not a rectal thermometer.” Hemingway portrayed Fitzgerald as naEFve and gauche, sexually and psychologically inexperienced, troublesome and irritating, hypochondriac and insecure, dependent upon and dominated by Zelda, a complacent and self-confessed cuckold. His emphasis on the weak, feminine side of Scott’s character subtly yet cruelly confirms Zelda’s accusations of his sexual inadequacy.

In this book Hemingway portrays all the characters, comically but venomously, as he saw them after they had quarreled. Ford Madox Ford was not “the heavy, wheezing ignoble . . . up-ended hogshead” until their battle over the Transatlantic Review in 1924. Gertrude Stein was not a disgusting lesbian until after she’d demeaned him in her Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas in 1933. Wyndham Lewis did not have the eyes of an unsuccessful rapist until he attacked Hemingway in “The Dumb Ox” in 1934. Fitzgerald was not an alcoholic failure until “The Crack-Up” articles appeared in 1936. Dos Passos was not a sycophantic and destructive toady until their fight about Spanish politics in 1937. Pauline was not a predatory bitch until he left her in 1939, and Martha was not a crass careerist until their marriage fell apart. Throughout his career Hemingway’s satiric humor was his weapon against the demons of sex and death. Anger inspired his wit and drove him to elaborately comic metaphors. A Moveable Feast, his posthumous time bomb, gave him the last word.