August, the deep end of summer. The wind heaves languorously in the heavy-canopied trees, the air defiantly material, the sun a giant fact in the sky. Where I live, this is a time of music wafting from open windows in every direction and the heavy smell of asphalt sinking into itself. It’s a time of cheap beer and slow speech, of nights that seem like the cool residue of days that have evaporated themselves into darkness. Usually by now I’m about beached out, beginning to think about the fall and how it will be arranged. Almost always, I am finalizing manuscripts.

For me, August is go time. I’m sitting on six or so months of poems I’ve been dutifully attending to — what represent my ambitions and quandaries of the year — and as I start to feel them ring with a sense of resonant completeness, a terrible anxiety sets in: I must do something with these. The decision to publish is definitely a personal one, and I would never suggest that writing has an end in it, but publishing is certainly a key pathway toward audience, and it’s also a way that your work can become a part of something larger. For those unaccustomed to putting themselves out there and submitting to the slush pile, as we so fondly call it, the task can be daunting and even emotionally fraught. But there are perfectly good ways to go about it that will keep you organized, give you great chances at success, and, most important — and I will argue this until the snows pile against the house — can actually help you improve your writing and how you think about it.

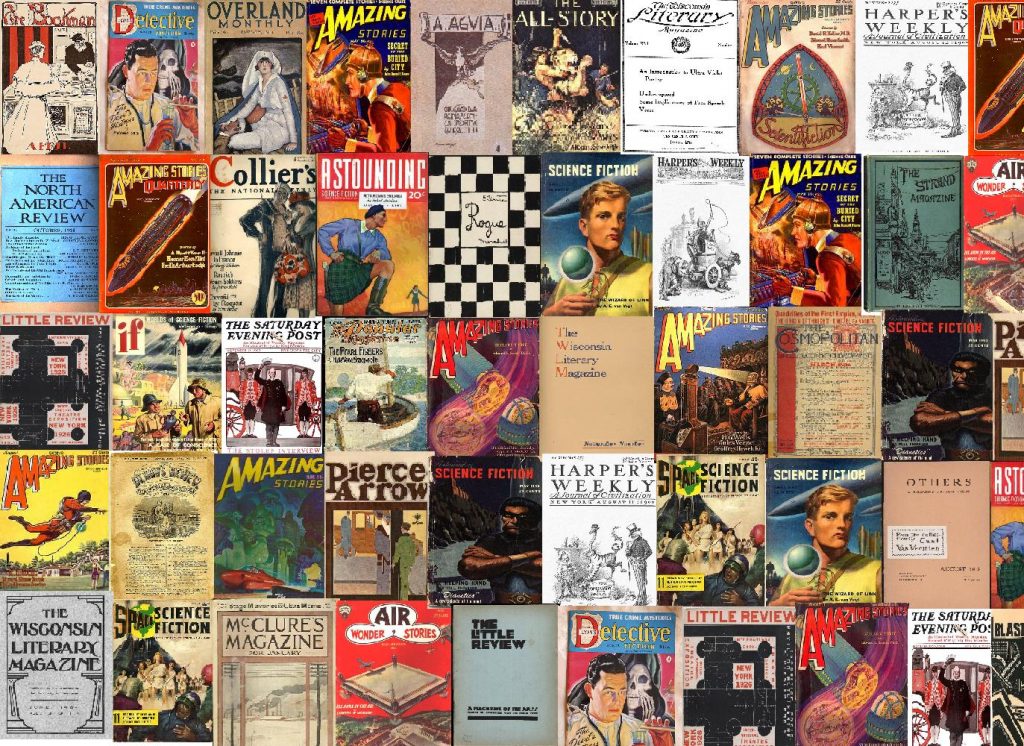

A lot has changed in the last decade. I wistfully remember trips to Office Depot, feeding dollar bills into the copy machine and writing out my address until my hand cramped just so I could ensure that I had enough Self Addressed Stamped Envelopes that would in all but the fewest cases be mailed back to me months later — the quarter fold creases still strong in them — with barely a 3×5 slip of paper that told me to move on. These days we have submission managers, and they sure have made things a lot easier. (It’s worth mentioning here that with submission managers often come a reading fee, a substitute for postage costs that checks unbridled submissions but also, some have contested, stinks of a pay-to-play scheme. I’m not touching that argument, though you certainly can.) But the question remains of where to submit, how to find and choose the best venues. Chances are you will have a handful of magazines that you already admire, and in most cases you should work your way toward trying to be a part of them. But chances are, also, that you will need to broaden your understanding of the vast landscape of magazine publishing. A lot of what follows will be common sense for those who have been doing this for a while. But for those who haven’t, here’s a little bit about how I go about it.

So first, the resources:

- NewPages: for a slightly more digestible overview, this is a great resource. They also have a directory, but theirs is run a little more like an ongoing trade publication — they regularly review current issues and announce calls for submissions. It’s a great way to stay current on magazines’ actual activity and not just their metadata.

- CLMP (Community of Literary Magazines and Presses): this is the principle trade organization of literary magazine publishing. They run one of the main submission managers (the other one is Submittable), but they do tremendously more than that, and perhaps sometime you can find yourself in one of their workshops or other events. What you should absolutely use them for, however, is their directory. It is a massive resource, with information — ranging from typical submission periods to ad rates to average page count — on hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of publications. Drop your specialty glasses over your eyes and have at it.

- And if you really want to stay current: well every year there is this little gathering called AWP, and within its grandest architectural spaces (unless we are talking about the Chicago Hilton) it hosts one of the world’s largest pop-up bookshops, aka The Bookfair. Walk around this behemoth. You might find some deals! You might get some buttons! You will definitely get separated from whomever you went in there with. But even if you can’t be there in person — or really, in addition to being there in person — you should peruse the exhibitor list. Here it is for the 2017 meeting in DC. I try to submit to magazines that have at least some presence — even a puny table (actually, especially a puny table) — at AWP: it indicates commitment and visibility, not to mention real people you could probably go talk to (more on being a nuisance in a bit).

- Less formally, but worth noting: is any old acknowledgments page. Did you really dig that short story collection? Somewhere in the front or back of it is probably a page that details where some of those stories first appeared. Maybe that collection was published in 1972, but who knows, a lot of magazines have been around since then and might still seek the same kind of work (just check one of this above lists to be doubly sure (or google them, ahem).

- Finally: ask your friends!

OK, so we have the great compilation, the official record. What do we do now? Here begins a section best titled The Ethics/Aesthetics of Submitting Your Creative Literary Work. You know that last bullet-list just felt so … right; let’s do it again:

- Submission window: this can be different for any magazine, but as a general rule submissions are open in the beginning of fall (roughly September and October) and the middle of spring (March and April). There are always outliers, and you’ll just have to plan ahead and stay organized. If you want to avoid those reading fees, many magazines who charge them will have Open Reading Periods, a limited time of free submissions.

- What to submit: the work. Probably a very simple cover letter with your contact info, short (SHORT) bio, and a list of the titles of what you are submitting (if it’s multiple pieces). Tell them if you are submitting simultaneously to other journals (pretty much the norm now, but some magazines want exclusive look—check first). Thank them for their time (most often it is unpaid). Don’t explain the work. Don’t explain your general philosophy toward life. Keep it short and professional. No comic sans. Or maybe comic sans.

- Quantity: this really depends, and it’s certainly different for poets and prose writers (and some other poets). I write pretty typical one-to-two page poems, and I tend to organize them in conventional manuscripts comprised of 3-5 poems (magazines will usually tell you how much work they will look at it). Typically during a submission period I’ll have about 4 or 5 of these manuscripts. I then send each manuscript of 3-5 poems to a maximum of 7 magazines — more often it is less than that. Your mileage may vary of course depending on your output, but one thing I’ll say is that I think submitting the same manuscript to more than 10 magazines not only creates headaches but is basically bad behavior (right, don’t be a nuisance).

- But where the hell should I send my poem/story/lyric essay?: Most magazines will have a paragraph or two describing the kind of work they look for. Usually I find these descriptions to be generous to the point of obscurity, but at the end of these paragraphs they will often suggest that you buy a back issue, check out the work online, generally familiarize yourself. This means you have to read, and who wants to do that? But listen to me: do it. Why wouldn’t you? Why would you send your work to a magazine that publishes nothing but stuff you hate? Read until you find what you like (and then keep reading that magazine, as a subscriber, a fan). For me, it gets even more articulated than that. Sometimes I write more narrative and accessible poems — I have a sense of magazines that look for this kind of work. Sometimes I write mathematically sonic work — I know where that should go. Sometimes I like to scream in my poems — there are magazines that relish in that, too. It’s an art, not a science, but you can find, understand, and work with these aesthetics.

This means a lot of reading, and of the purpose-driven kind, but this is one of the best things you can do for yourself. Some could certainly argue that reading with one’s own work in mind is a corrupt form of reading, but I totally disagree. The more I seek out magazines to publish my babies, the more I understand and thrill in what other people are doing — the more I have a sense for the scenes and which ones I find affinity with. It absolutely affects my work — I write to trend, and I write against it. I pick pieces from this and that, and I hear my voice as a social assembly, myself as an artistic agent in a particular moment in poetic history. Sound grand? It’s really part of the everyday, the incremental way we collectively shape poetry’s direction. And you can be a part of it, too, with an internet connection, a little time, and an earnestness of mind that your work does indeed have a home out there.

Image via everywritersresource.com.