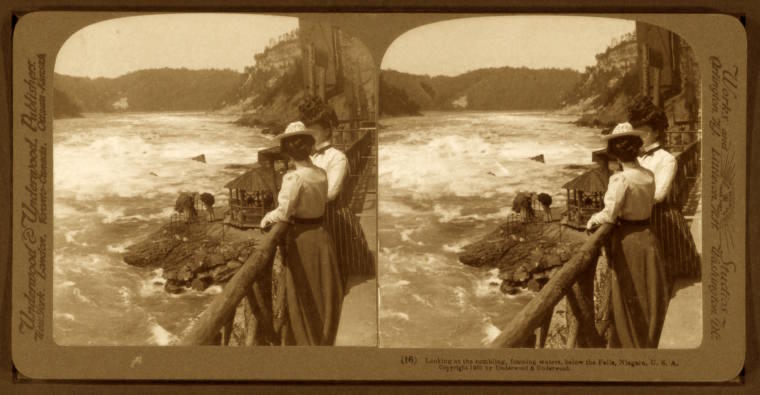

In 1901, a woman threw herself over Niagara Falls in a barrel. She was the first to survive this trip, which she had executed specifically for fame and fortune, though she earned more of the former than the latter. Despite world-wide headlines and a number of speaking engagements, she remained poor, hawking photo-ops and signatures to tourists. She also wrote a novel about the experience.

A novel about the experience. I can’t be the only one cringing, right? It sounds like turn of the century clickbait, or the only-slightly-preferable woman’s memoir of desperate choices and self-discovery: “I prayed every second I was in the barrel…” She could call it, Eat, Pray, Get in a Barrel.

On the other hand, why shouldn’t she write a novel? Annie Edson Taylor’s inner depths might well have been fascinating, and her life was material enough. After her husband and child died, Annie wandered the country, teaching, afraid of the poorhouse, trying to figure out how to live. On her sixty-third birthday, she jumped off a wet cliff. What brings a person to that conclusion, I’d like to know, although by today’s standards her instincts for self-preservation – act stupid, get famous – were spot-on.

Either way, it’s clear that Annie’s intention was not to express but to sell herself, while I like to think that most of my experiences have been ends in themselves, even if, secretly, I knew I would write a poem or two about them later. Writing was always just a way for me to process my life, and to have my words read never seemed like the point, though of course, I was mistaken.

I’m interested in how to write about the self, and what to do with that writing, because what happened at a certain point in my life is that I went over the falls – so to speak – realized I liked it, that I had perhaps always wanted to do it, and would probably do it again and again. At some point there is language for that, a definition, a narrative. I fell into women; the word I chose for that was queer. I didn’t want to hawk the story on the tollway, but I thought it might be worth some poems.

*

Never had much to write about anyway; studied writing, a self-cancelling path. “What’s your subject,” someone asked when I said I intended to write. “Hemingway would have been nothing without the war.” Well, war seemed complicated, and what right had I to learn about war? We didn’t have that in my Ohioan suburb.

When I was a kid, it seemed like there was a world out there and me in here, and we could go on happily ignoring each other forever. I liked being invisible. Being in the world felt like stumbling into an electric fence, but books turned down the wattage, they were part of the “in here,” and they let me exist without the pain of actually existing. I learned a written world and understood myself within in, which turns out is different from lived experienced. Oops.

And yet I remember when an early attempt at writing made the inner and outer crumble together; I was in fifth grade and had written about a storm for an in-class prompt. As the teacher was handing the assignments back she paused to read a few aloud. She read mine, not giving away my name, and as I listened to her read that paragraph about black clouds and lightning and rain on the horizon, I felt uncertain as to whether those words belonged to me. Had I really written that? Why did the phrases sound that way, no longer part of my inner rhythm, but outside of me, estranged? I felt inside and outside of myself at once. I was proud she had chosen to read it, but glad she had not said my name.

Not until my mid-twenties have I been able to acknowledge that in fact I do not just exist in here, but out there, and that my writing has to exist out there, maybe even with my name attached. You see, if being with men was a convenient way to stay invisible, also being with women made me visible, because after all – scary as it was – I had to be seen, literally be read, if my lived experience was going to change. Once I let myself be seen, and to exist newly, I discovered that there was not a divide between myself and the world the way I had always thought; I was part of it, caught up in all its pleasure and pain. Recognizing myself made me realize that I did exist in the world, not just in books – which made me suspect that writing could be a tool within the real world, not just within my private one.

*

I didn’t prepare with theory, with stories; there was no way to prepare. Yes, I wanted desire to be true the way a sentence can be true, but believe me, as an expert over-thinker, not everything can be thought through. That came after the fall. The wreck and not the story of the wreck seeks Adrienne Rich, but I, the wreck, needed a library card fast, needed Stephen with her big hands, and Eileen Myles with her stupid Madras shirts.

And to my astonishment, I discovered not just literature but a community, in all its lived complexity. (“Good thing we don’t look gay,” joked a friend in Mississippi, the joke being that we did – I did!) It was different than being an ally; the idea of claiming my own community had never occurred to me. I never knew that between myself and the world there might be a buffer, a belonging, where the risky parts of the self can breathe.

That turned out to be an orienting force, a source of clear voices, important in the context of the Mississippi bill and Trump and Orlando and everything else, even considering my naiveté and privilege. I found too that I might have some measure of responsibility – not to myself, but to a history, a canon. Maybe I could carry that forward, at least in words if not in lived action. No, wait. I mean that writing can be lived action. That’s all I realized, really.

*

Over the Falls, Annie called her book. “It is a plain recital of fact,” the introduction insists. “Even in its plain way, this little book has the distinguishing feature of being a story thoroughly original; a story which no other one of the million of people on this earth can truthfully tell as Annie Edson Taylor has told it.” Alas, she was probably the last person in the world to be thoroughly original. But in the end I like her boasting, her self-promotion. My story is worth reading. Couldn’t hurt to come to the page with that in mind; that isn’t selling out, it’s just what writing is.