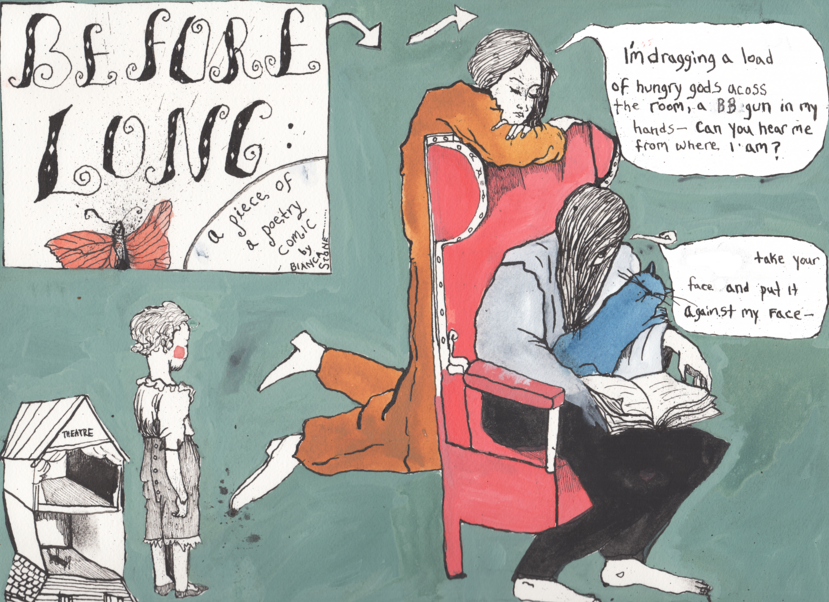

The following is an interview with Bianca Stone, whose new book, Poetry Comics from the Book of Hours, is forthcoming from Pleiades Press in May 2016.

*

I’m really interested in your process. In general, do you begin with a comic, or a poem?

For me, poetry is always first and foremost. Honoring the words is the most important aspect of making a poetry comic. Text will always lead the images.

The process of making a poetry comic is vital, since I don’t plan out in advance; don’t plot and storyboard. The process is where the piece determines itself. It’s a lot like composing a poem on a blank page: you have tools (language, memories, obsessions, sound) and you work with those in a sort of simultaneous process of improvisation and intent. So, even if the poem is already written, it’s going to become something totally different in the end.

Most of the time I just choose fragments/lines of poems to combine with an image. I don’t do an entire poem.

I like that you allow the reader to see some of the choices you’ve made (in terms of crossed out words/ erasure, and also, changing the words when you paint/draw/illustrate); was it difficult to include this? Or is exposing your process natural and comfortable for you?

Mistakes have become part of who I am as an artist. When something happens in a visual piece that I want to change, I work with it—instead of starting over. I don’t give up on things. I used to give up on a lot when I was a teenager. I consciously decided instead to keep going though my faults instead of running from them. I break them down and rebuild them. It allows for a kind of texture I find very satisfying. I respect imperfection and rawness is art.

Whiteout was at first a practical issue, since I never work in pencil. But it’s become an invaluable part of my medium. I like to call it my erasure/replacesure method.

Many of your comics contain words and text, but the text is not always visualized literally in your comics. I’m guessing you’re instead trying to visualize the feeling of the words; is this true? Or can you write a bit about how the visuals support the text?

Many of your comics contain words and text, but the text is not always visualized literally in your comics. I’m guessing you’re instead trying to visualize the feeling of the words; is this true? Or can you write a bit about how the visuals support the text?

It’s an incredibly important point. I harp on it endlessly as a teacher of poetry comics. I think my answer would start with a question: WHY have images? Poems don’t need images. In fact, images take away from the imagination of the reader. They stop the reader from creating meaning within their heads—essentially the most important part of experiencing a poem. The visual will always trump the textual, that’s just how our brains work. So you’re going to change everything when you put an image with text.

Take for example a Robert Frost poem, “The Road Not Taken.” If you were to make a poetry comic that was drawing of two paths forking off in a birch covered grove of the woods, with an dude standing in front of them like his hand on his chin looking quizzical, I mean, redundant or what? Who cares? What does it DO beside satisfy the most lazy part of us? Already Frost has a very straightforward poem, visually. If I’m a poetry-comic-maker, than I want to complicate the fuck out of it and make a whole new poem out of that poem. (This is also why I firmly believe in poetry comics being your own images and text).

So, let’s say I was using Frost’s poem. I might have the first line, “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,” and I draw that line coming out of the mouth of a whale, and the second line, “And sorry I could not travel both” the whale again, but leaping out of the water onto a giant plate with a fork and knife beside it. OK, so now we’re thinking about the meaning of those lines very, very differently. In a way, we’re free of the tyranny of the literal. Our imagination is piqued. The image serves as another line of poetry, self-sufficient, but working in tandem with the words. Clearly, the possibilities are infinite when “illustrating” a poem.

For me this is the critical difference, the defining feature of what makes something a poetry comic: the images function autonomously, as a line of a poem would, to the other lines of the poem. The images are not there to translate what is already there. They’re not there to visually help you understand what’s “happening” in the poem. They are there to seamlessly interact and allow the reader space to feel and create meaning on their own. For this reason, I think poetry comics can be wildly helpful to talking about how poetry works.

As a movement artist, I have a complicated relationship to my art and my body and while reading your new book, I kept thinking about this; is the same true for you?

As a movement artist, I have a complicated relationship to my art and my body and while reading your new book, I kept thinking about this; is the same true for you?

Oh Christ, yes! The body is very complicated and important to me. I can’t help it—it just happens. It’s probably a lot to do with being a woman. I mean, we suffer a lot with expectations from culture, and my body has always been very troublesome to me.

I think we’re trying to understand the body, control it, test it when we bring it into our work.

I love movement in artwork. There was something disturbing to me about the stiff way people drew bodies when I was young; the poised beautiful girl, etc. as accurate as possible. I always liked the gnarled beautiful ugly bodies in Egon Schiele’s paintings and the drama of movement in religious renaissance work.

Poets naturally deal with the body/mind conflict, and I think our society at large is starting to explore the relationship more, now that science is catching up with poetry!

Have you always been supported in your artistic endeavors?

You know how well-to-do famous-doctor-families are like: You have no choice but to follow the family tradition of going to med school? It was like that, but with creativity. My mother is compulsively creative. She can’t stop! And I’m just the same. And my grandmother had me writing poetry before anything else.

Can you tell us a bit about your grandmother, Ruth Stone, and the foundation you started in her name?

Grandma and I spent a huge amount of time together because my mom was all on her own. Basically I was raised by the two of them. We depended a lot on Ruth, who lived entirely on her work as a poet and teacher. I lived with her every summer at her house in Goshen, Vermont, about twenty minutes from mom’s house, and many months with her in Binghamton where she taught in the winter. The house in Goshen is magical. It’s 4.5 hours away from Brooklyn. Goshen has less than three hundred residents and is in a national state forest. Very rural, on a dirt road–no stores or anything. It’s a perfect writing space. So much of her poetry was written there. Poets, students, and colleagues all would come up and stay weeks as a time, writing and reading and talking with grandma. Since she was so insanely devoted to poetry—insisted on it, encouraged it, and pushed you to write it—it made the space very special in terms of inspiration. She left the estate in Trust and we started the foundation in order to raise money to fix it up, to make a writer’s retreat and art space. We’ve also got big news! The Vermont Advisory Council for the National Register for Historical Literary Landmarks unanimously approved the The Ruth Stone Foundation house to become a literary landmark.

I’m always feeling like my poems are never finished, even when they’re published. Do you feel this way about your poetry comics?

Totally. When I put this book together I made changes to many of the pieces (from when they were originally published) and it gave me a lot of satisfaction. Still, I look through it wanting to change this and that. I keep a lot of fragmented poetry comics laying around to mess with again. For me, some of them I accept as DONE, others just never feel done, no matter how much I fiddle. Eventually you need to stop working on something. Overworked seems worse than undone, doesn’t it?

But I think in our hearts, you’re totally right. “Poems are never finished, only abandoned.” (Who said that?) Dissatisfaction is part of our process, and it never goes away. It’s probably what keeps us going. But of course, you reach a point like: THE END. And you have to let go. It’s totally devastating, cathartic, and necessary. Like kids going away to college.

Who are you reading / looking at right now?

I’m on a total, high-speed prose kick. Which is unusual for me. I just read some great women fiction writers: Donna Tartt and Nell Zink’s books. Blown away. I’m so impressed with what fiction writers can do. I want to try that more. I want to make shit up! Also, mom dumped a bunch of my old paperbacks on me, and I randomly reread Herman Hesse’s Damien. So wonderfully dramatic and interior. And what’s also filling my mind is nonfiction, I’m a big article reader, and books on how our brains work, and cognitive errors, and a new surge of rational self-help-neurology shit. I find it fascinating.

Frank Stanford’s poetry, especially the recently released Third Man Records one with the typewriter facsimiles of his first drafts. I’m an assistant to Sharon Olds, and I’ve been reading a ton of her new poems for her book of Odes, (out next fall) which is just brilliant.

Do you have any advice for those who are working in multidisciplinary arts? Anything that anyone said to you that was helpful?

Don’t worry about where it fits in, or how to explain it. I use the term “Poetry Comic” because it’s just better than nothing. But I don’t feel beholden to it beyond my own evolving definitions. Trusting what you do best is key, even if it doesn’t make sense at first, or look like anyone else’s. Fear—that you’re not like someone else, or recognizable—will harm your work. GO ALL IN. Gather a lot of information, read and see a lot, absorb and be humble, and then when you sit down to do your own shit, forget everything. Don’t question it, just follow it—like a mistake you’re going to fix no matter what. Like a mistake you’re going to turn to your advantage.

The secret is that readers really like multidisciplinary arts. It gives them more to work with, and surprises them. Be excruciatingly patient. Never settle for something ordinary. And if you do something that sucks and fails, then just take a break and start over again. Failure is imperative to moving forward. If you’re going to collaborate with someone, then make sure it’s someone you really feel akin to artistically, and who you can have frank and open conversations with. Remember that poetry, art, writing—they’re always evolving. Nothing is set in stone. We’re the ones who create a bend in the endless arching history of art. It’s a powerful place to be.

*

Find out more about Bianco Stone at poetrycomics.org, or follow her on Twitter @biancastone.

Author photo courtesy of Bianca Stone. Poetry comics taken from “Poetry Comics From the Book of Hours.”