“I dwell in Possibility – / A fairer House than Prose –”

–Emily Dickinson

“A story is not like a road to follow… it’s more like a house. You go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows.”

–Alice Munro

*

No, I’m not one of those writers who puts off “the work” by turning on the TV. My vice, I think, is worse: I’ve developed a method of squandering whole days of writing by doing nothing but writing about writing. Sometimes I’m writing about the project at hand, trying a low-stakes long-cut to the heart of the story, which almost never works—the insights and revelations lose all their luster whenever I try to bring them back with me. More often I lapse into muttering meditations on the writing process itself, trying to pinpoint exactly where I’ve gone wrong by fabricating woefully extended metaphors: Writing is like sculpture… Writing is like jazz… Writing is like a garden path…

To think of the thousands and thousands of words I’ve enlisted for such vain purposes! And the deception is airtight, almost. It looks like writing, it sounds like writing, it has to do with writing. It is “writing,” if we’re equivocating. But it doesn’t feel like writing—no, it’s too easy. I enjoy it too much. That is, until I realize my writing time is over and my story is just as doomed as it was when I sat down. At which point I pack up my things and trudge away in self-pity.

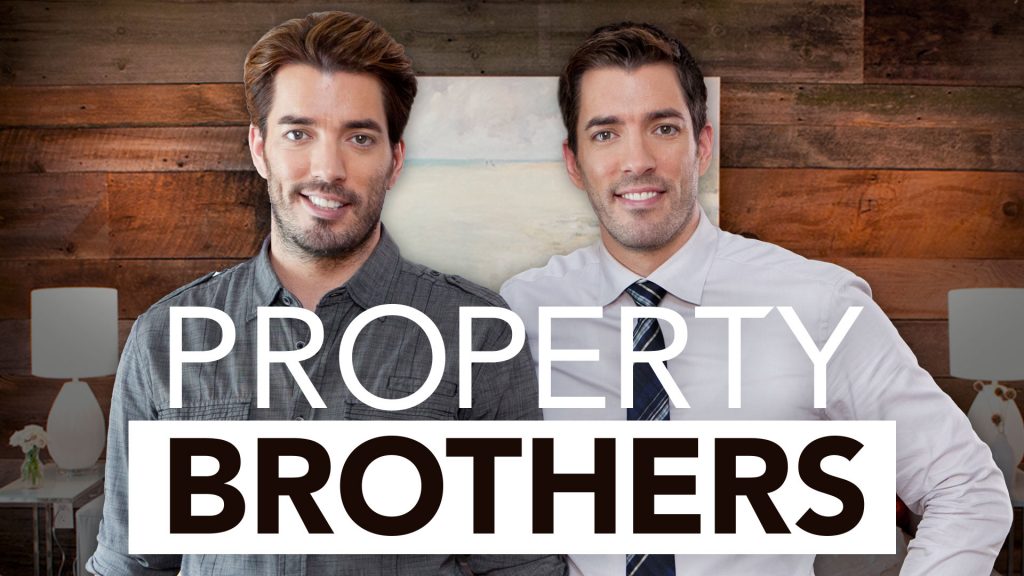

After dinner, still sulking, is when I turn on the TV. Lately, it’s Property Brothers, a Canadian home renovation TV show starring Drew and Jonathan Scott. For anyone who hasn’t exhausted quite as much of Netflix as I have (still catching up on the Restaurant: Impossible collection?), in each episode the Brothers shepherd skeptical homebuyers, usually a couple, through the process of buying and renovating a fixer-upper. Property Brothers fans (I use the term loosely) will be accustomed to the show’s satisfyingly predictable formula: after a few well staged illustrations of the inadequacy of the couple’s current home, the Brothers take the couple to view their “dream home,” complete with every undermount sink and en suite bathroom on their wish-list and at least $100,000 over their budget. Next the Brothers show the couple a handful of fixer-uppers—these places are floored with equal parts shag carpet and linoleum, partitioned into college apartments, dangerously wired, freighted with asbestos, and full of other people’s crap. The couple looks around, not really listening to the Brothers, and nearly always says something like this: “I just can’t see it.” But eventually each episode ends the same way: the couple in tears, thrilled with their new, renovated home.

Yes, the analogy is limited. But, I have mused, isn’t writing a story at least a little like an episode of Property Brothers? Before they were TV-star real estate agents, Drew and Jonathan Scott aspired to be actors, with credits on Smallville and X-Files. Surely, at some level, when they talk about old homes and updated kitchens, they’re really talking about the tragic and noble pursuit of Art?

As writers we have all toured dream homes we’re too poor to afford. Maybe Katherine Anne Porter’s “Noon Wine,” for me, or Tobias Wolff’s “Desert Breakdown, 1968,” or Danielle Evans’s “Virgins.” Yes, I tour these stories and compile my greedy wish-list: a mysterious stranger, I like that; a road trip gone wrong, of course; a heartbreaking decision both right and wrong at the same time, I wouldn’t want my story to go without one of those. I put down the book and open the computer. There’s my draft, all at once in various states of disrepair. I read back over it and wonder with distaste when and how, like floral wallpaper, these sentences had ever seemed a good idea to anyone. I hold my own story against my dream stories, I hold my vision for my story against its ruinous half-state. I moan: I just can’t see it.

But unlike on Property Brothers, there’s no easy answer here, no ready combo of hope, will, and trust that will land us someplace livable. My computer is littered with drafts abandoned, aborted, forgotten. Sure, once in a while a story manages to survive my doubts and excuses, my terrible habits. Briefly, I’m happy. But then I start a new project or try to resurrect something old, and once again I hear myself saying it: I just can’t see it. The frustration I feel with every new Property Brothers participant is the same I repeatedly level at myself—how predictable, how irksome and stupid we are! Just as they “can’t see” past one ill-advised light fixture, I find myself hung up on a single wonky sentence, a lone imperfect word, and my entire day is shot. Again and again I forget everything I know about revision, renovation. I lose heart, I close my story, I open a new document: Writing is like an episode of Property Brothers…