I don’t know if you’ve heard, but there’s this guy running around claiming to be Chinese, and he happens to write poetry, and, right, he’s not Chinese. Also, it worked. This guy, Michael Derrick Hudson, writing under the pseudonym Yi-Fen Chou, now has himself a Best American Poetry badge. He’s an imposter, a charlatan, appropriating ethnicity as a tactic for getting an accolade, or maybe as an activist performance to highlight the injustices of reverse racism. A lot of people have been talking about it, passionately, personally, with anger and frustration, laying out an arsenal of theories and logics to establish or reinforce what we might call the proper ethics of artistic identity, of identity politics and the right to voice.

At this late hour in the news cycle of the Yi-Fen Chou debacle there has been enough conversation to offer a fairly coherent set of coordinates that map the proprieties of ethnic and racial identity in contemporary American poetry, in the immediate, and in American culture more broadly construed. If you want the news, you can read what Jennifer Schuessler has to report at the New York Times. If you want to hear it straight from the editor—Sherman Alexie—who has been wringing his hands over the affair, you can read his extraordinarily thoughtful response at the BAP blog. If you want a roundup of the conversation, the Poetry Foundation has it for you.

What follows here is a rough and succinct guide to the central issues that constitute this story, the ways we think about who we are and whether we can pretend to be someone else. A nota bene—you will no doubt notice my name as an Asian one. I have many personal feelings on this matter, but for the most part my aim is simply to break down the dialogue into the most meaningful and illuminating categories that I can.

So let’s get on with it.

~

Your Parents Always Told You: Don’t Lie

First and foremost: Michael Derrick Hudson is a liar. So is anyone who has ever written under a pseudonym, or anyone who has told a fictional story. So that implicates a lot of people. Context, however, matters greatly. Sometimes we expect to be lied to. Sometimes we see a playful name and would never assume it’s real, with any origin, any claim to lineage. But that’s not the case here. When we see a name like Yi-Fen Chou, the context is one of honesty—we expect a Chinese woman to bear it. In cases like these, lying isn’t artistic, and it isn’t playful—it’s deceit.

So Let’s Fight Back, Punch for Punch

Deceit is hurtful. It makes one angry. And when we get angry, we retaliate. So we have the #WhitePenName generator, which maybe comments on the benefits of passing as white (offering a technology to level the playing field), but is also certainly meant to give Hudson a dose of his own medicine. It legitimates its ethics by calling itself satire, but it’s pretty tricky business if you ask me.

White Guys Are People, Too

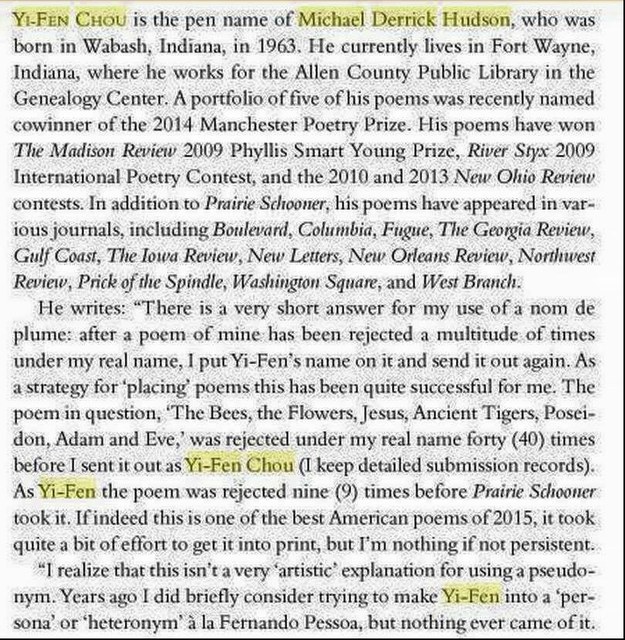

And maybe Hudson’s deceit is to prove a point, that white guys have it hard. No doubt, some do. Maybe Hudson does—he certainly says he does in his contributor note. “It took quite a bit of effort to get it into print, but I’m nothing if not persistent,” he says. This note is important. Maybe in some ways, it is part of the poem itself, part of its art. Maybe he’s unmasked himself on purpose. He doesn’t want to be misconstrued as Yi-Fen Chou. He is making a point, that as a white man, he gets rejected. As a Chinese woman, he still gets rejected, but not as much. He’s showing that we favor minority voices for the sake of their being minority, and that there are victims in this story, people like him, and, perhaps more important, the deserving poetry they write. What he offers here, really, is a gotcha.

The Illogic of Reverse Racism

But isn’t that bullshit? Aren’t most of the celebrated American writers today still white? A lot of the responses have been quick to cite the statistic that Roxane Gay pointed out at the Rumpus in 2012—that just about ninety percent (give or take—as you can see below—but still, a lot) of the writers reviewed at the New York Times are white. Ken Chen, executive director of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop in New York, probably puts it best in his piece on NPR:

American literature isn’t just an art form — it’s a segregated labor market. In New York, where almost 70 percent of New Yorkers are people of color, all but 5 percent of writers reviewed in the New York Times are white. Hudson saw these crumbs and asked why they weren’t his. Rather than being a savvy opportunist, he’s another hysterical white man, envious of the few people of color who’ve breached their quarantine.

People might lie, but numbers don’t. Yes, academia and the arts might be baroque with social correctives, and those might formulate an environment hostile to writers who come from demographically privileged backgrounds, but it looks those writers are still doing just fine, even today.

So What, Good Poetry is Good Poetry

But numbers such as these are just one way to look at it—a pragmatic way, really. There is still the absolute way: that good poetry is good poetry regardless of who wrote it, and that in today’s climate of affirmative action, of corrective measures to include marginalized voices (even if those efforts only result is some ten percent of spoils) good poetry is being overlooked in service of perceived social justice. And it works equally in reverse: that effort at social justice tokenizes the deserving writers of color who benefit from it. Isn’t this the real argument that Hudson’s actions are making? Doesn’t he have a normative point, one that is actually sympathetic to civil rights, that says race and ethnicity shouldn’t matter at all? Do the work, get paid. No nepotism, no acknowledgement whatsoever of who the author is. Isn’t this real democracy? Alexie, in his response, has the posture of fessing up to this, swallowing the hard pill of recognizing his own racial favoring:

I did exactly what that pseudonym-user feared other editors had done to him in the past: I paid more initial attention to his poem because of my perception and misperception of the poet’s identity. Bluntly stated, I was more amenable to the poem because I thought the author was Chinese American.

Maybe Hudson is crying out for color-blindness, demonstrating the injustice that can happen when we pay attention to the identity of an artwork’s maker.

Oh Right, Marxism

But hey, wait a second; haven’t we already agreed that art is inextricably tied to the conditions of its production, including the identity, privileges, and challenges that its creator has faced? Phew, good thing Jia Tolentino at Jezebel is here to remind us:

Identity politics, with the great rivers of well-meaning smarm and short-sightedness that run through it, is exhausting enough when leveraged for basic equality; when leveraged for a white man’s ability to get published, the whole thing feels unredeemable. But we can’t give up on the fact that the source of a thing matters. Rachel Dolezal is just not the owner you want for your weave salon; Jonathan Chait is just not the best voice to argue that political correctness has gotten out of hand. Ryder Ripps’s “Art Whore” project was banal with him behind it; with a sex worker as the artist, then we could talk. But, of course, a sex worker wouldn’t have gotten anywhere near the amount of attention. And here we are, back at the boring old start.

Good poetry is good poetry because of who wrote it. If you want to get fancy about it, it’s an index of the culturally defined experiences of the author and the ways that author has taken agency within them, has interacted with his or her own received cultural and historical condition. Poetry isn’t good simply because it has kickass slant rhyme or wicked trippy imagery but because it employs those techniques mimetically to engage heritages and traditions that constitute the wisdom—and oppressions—of most acute concern at a given historical moment.

The Idiocy of Merit

Which is to say, value might not be commensurable with merit. Merit—the goodness and badness of a thing—is, some claim, a fiction. Kazim Ali, in his wonderful open letter to Aimee Nezhukumatathil at The Rumpus, reminds us of Adrienne Rich’s bold refutation of the “Best” when she edited it:

Maybe we need a different approach. Maybe we don’t need a “Best,” especially not one published by a corporate publisher with guest editors chosen through some nebulous process. The most interesting volume of that series (in which I also appeared once) is the one from 1996 whose editor, Adrienne Rich, spent her introduction arguing precisely against the notion of “literary merit.”

Apples and oranges. How can we possibly say—especially in this era of intense language production in every possible format—that everything falls along a neatly ordered hierarchy from shit to gold? Surely you can make some pretty rough guesses—this is not to say there isn’t craft but precisely that craft has developed so well, become so diversified in the extremely privileged time we all live in, that at the level of the BAP merit has evaporated as a tenable criterium.

The Best Italian Restaurant in the World is in Chicago (Oh Right, Post-Structuralism)

It’s on the corner of Grand and Halsted, and it’s called Piccolo Sogno. Oh were you thinking it might be in Bologna? Nope. Which is to say—beware the fallacy of the authentic. If merit is sufficiently destabilized, so is ethnic authenticity. Back to Sherman Alexie, who in his confessionals confessed to this:

It didn’t contain any overt or covert Chinese influences or identity. I hadn’t been fooled by its “Chinese-ness” because it contained nothing that I recognized as being inherently Chinese or Asian. There could very well be allusions to Chinese culture that I don’t see. But there was nothing in Yi-Fen Chou’s public biography about actually being Chinese. In fact, by referencing Adam and Eve, Poseidon, the Roman Coliseum, and Jesus, I’d argue that the poem is inherently obsessed with European culture. When I first read it, I’d briefly wondered about the life story of a Chinese American poet who would be compelled to write a poem with such overt and affectionate European classical and Christian imagery, and I marveled at how interesting many of us are in our cross-cultural lives.

What is “Chinese-ness”? For that matter, what is “American-ness”? The best we can say is that certain gestures and concerns can signal an ethnic identity and, from there, engage a more universal experience as it is affected by that identity. But it’s fairly slippery and inherently requires some kind of stereotyping, or, at least, reduction of experience into familiar cultural terms. And then there’s the matter of the nearly infinite divisibility of identity. Asian—sure—so like, Han Chinese? Or a Tokyoan? Or do you mean Okinawan? Or Buryat, maybe? Are we including South Asians in this? Tamils, or Bengalis, or Sikhs? And I’m not even talking about neighborhoods, or castes and clans.

The atomization of identity means that any display of identity is, on some level, an improvisation, an on-the-fly composition of elemental parts that can differ from moment to moment. Identity is always mediated—constructed, performed, and shaped, something that exists in the space between performer and audience.

So It Doesn’t Matter Then, If Identity Is Always Mediated, My Appropriation is Just Another Mediation

Sure, okay, but that doesn’t make you a good person. Remember that thing we said about lying and context?

Ouch, I Hurt—Let’s Make Some Money Because of It

Besides, people of color, Others, share an experience that white men simply can’t lay claim to. That experience is marginalization—a distinct form of trauma. Maybe that’s what people like Hudson are secretly after. Maybe in their ethnic persona they can exercise the demons they feel no one would otherwise care about. Jenny Zhang writes movingly in her piece at the Huffington Post about many facets of this situation, but especially about the commodification of trauma:

White supremacy tries to reduce people of color to our traumas. Resisting white supremacy means insisting that we are more than our traumas. One quick perusal through the shelves of world literature in any bookstore confirms just what the literary world wants to see from writers of color and writers from developing nations: trauma. Why, for example, is the English-speaking literary world mostly interested in fiction or poetry from China if the writer can be labeled as a “political dissident”? Even better if the writer has been tortured, imprisoned, or sentenced to hard labor by the Chinese government at one point. Surely there are amazing Chinese writers who don’t just identify as political dissidents just as there are many amazing white American writers who don’t identify, or rather, are not identified as one thing. Why are we so perversely interested in narratives of suffering when we read things by black and brown writers? Where are my carefree writers of color at? Seriously, where?

Sympathy is a gimme; trauma is compelling—isn’t it the magic potion that gives any narrative its existence, at least as conceived in your run-of-the-mill fiction workshop? One of the most stirring lines that Ta-Nehisi Coates has recently offered is this one: “In America, it is traditional to destroy the black body—it is heritage.” How do you reconcile his truth with Zhang’s? How do you decry the violence against marginalized communities at the same time that you say they will not be defined by it?

To me, this is the ultimate puzzle of the Yi-Fen Chou case, and of racial and ethnic politics more largely. Hudson’s act is a mockery and affront because it offends the respect that suffering demands. As Hua Hsu eloquently puts it in the New Yorker, “it ridicules the ambient self-doubt that trails most people from the margins who enter into spaces where they were never encouraged to belong.” And yet, there is much that is joyous in the experiences of the Other, and part of that joy is the necessity of authors of color as crucial constituents in the American voice, as constituents whose historical exclusion paradoxically positions them as agents and celebrants in a larger, multi-cultural assemblage—bound together precisely by that exclusion (“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses,” after all)—one unavoidably conditioned by everything we have been discussing. Internment camps are part of the Asian American experience, as is excellence in STEM fields. Copper Tan and Spa, blocks from my house, is part of it, and a little farther away, the Zhou B Art Center. A guy named Jeb is part of it, as is someone named Nam June Paik and someone named Kristi Yamaguchi (no, we are not related). And now, for better or worse, so is this guy whose real name is Michael Derrick Hudson.