In March of 1949 the town of Churubusco, Indiana (population 1,200) made national headlines as a result of a turtle sighting in the murky waters surrounding Fulk Lake. This wasn’t just any turtle, but a turtle of monstrous proportions—400 or so pounds of skin and shell, as big as a car, or close.

The creature was first spotted the previous July, when locals Ora Blue and Charlie Wilson encountered it during a fishing expedition. “We saw the big waves a-rolling and up came that turtle,” reported Blue. “… I saw that big head sticking up and the waves going away like it was a submarine.”

Gale Harris, who owned the lake, remained skeptical. At least until the following March when he and his friend, the reverend Orville Reese, spotted the beast while repairing Harris’s barn roof. At first they shrugged off the sighting, though when the turtle resurfaced the following day, curiosity got the best of them. Harris and Reese gave chase, scurrying into the nearest rowboat and paddling toward the disrupted water. Within minutes, both men claimed to have spotted the turtle on their respective sides of the boat, and after a bit of bickering, came to the startling conclusion that they were, in fact, staring at the same enormous turtle.

For me, a 10-year-old already leery of lakes, the prospect of a giant turtle just 15 miles from home did little to assuage my fear. I couldn’t help but imagine that steely-eyed, sharp-beaked creature awaiting my inelegant pencil dives and cannonballs while camouflaged in his bone-plated shell. He was the stuff of nightmares, at least my nightmares, and after awakening to a few cold sweats, I began to play it safe by steering clear of local lakes altogether. Yet decades later, the story would have the opposite effect—compelling me to pay a visit to Churubusco, to confront that turtle once and for all.

On a cool day in March I park the car and make my way inside the Churubusco History Center; which, in truth, is less a “center” than a modest, one-room structure complete with a table and a couple of chairs. Yet what the center lacks in flashy displays it makes up for in guys named Chuck. There are two Chucks total, both of whom welcome me heartily to the history center and agree to tell me the tale.

“Well, it really got going in March of 1949,” Chuck Matheiu begins. “That’s when Gale Harris began trying to capture his turtle.”

What began as a small town curiosity soon became a national story. The press corps descended, and along with them, thousands of others anxious to catch a glimpse of the turtle they called “Oscar,” or, “The Beast of Busco.”

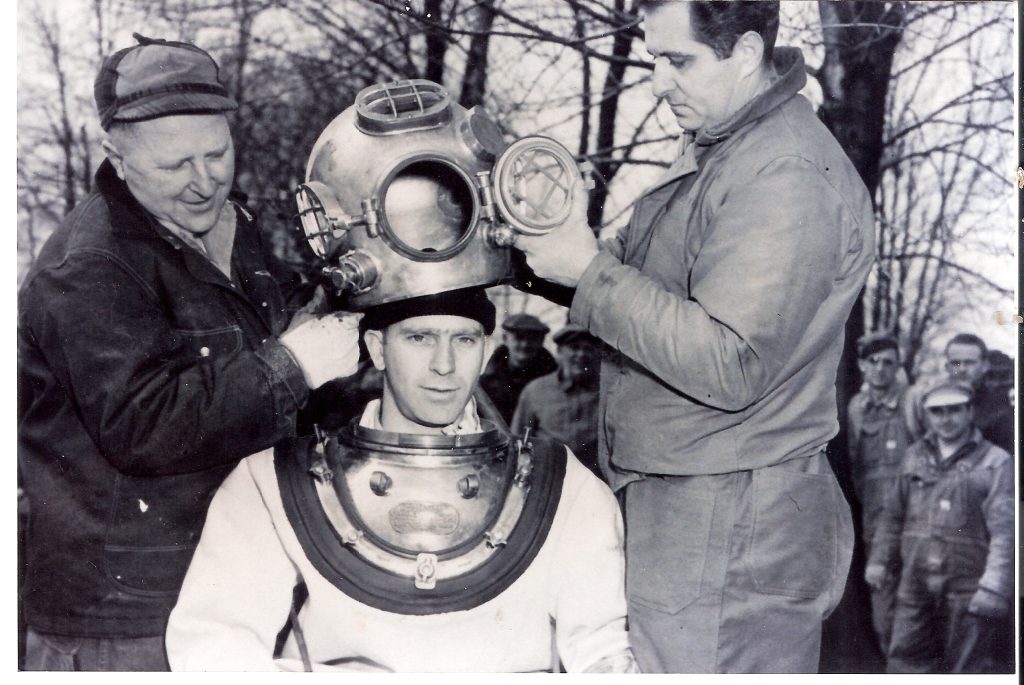

Wholly unprepared for such an influx, the Churubusco Community Club met in special session to formulate a plan. They began by launching the Turtle Committee, whose job it was to oversee the safe capture of Churubusco’s most famous resident. After much debate, the committee agreed that the search required a seasoned diver, and in an effort to obtain one, extended an invitation to Fort Wayne diver Woodrow Rigsby to try his luck in the lake.

Donning his diving suit, Rigsby submerged, only to bob back to the surface rather anticlimactically after his helmet sprung a leak. Three days later a second diver, Walter Johnson, fared slightly better, though after two and a half hours yielded nothing, he, too, focused his efforts above the waterline.

For months Harris and his compatriots devised any number of turtle traps, though none could withstand Oscar’s strength. They tried nets, too, but never raised anything but muck. That spring, the men of Churubusco spent many sleepless nights shining lights into dark water, and when that didn’t work, they enlisted the help of professional turtle trappers from Tennessee. Yet after the professionals proved equally unsuccessful, Harris—perhaps summoning his inner Ahab—was said to have vowed to capture the turtle even if he had to “borrow a diving suit and go after it himself.”

But first he tried a new approach, betting on Oscar’s more amorous instincts and releasing a 200-pound female sea turtle into the lake. Suffice it to say, it was not a love connection, and by mid-May, Harris and his team had removed the female sea turtle and took to dragging the lake with hooks.

None of it worked—not the nets, not the hooks, not even the girl. Running low on tactics, the megalomaniacal Harris attempted his Hail Mary—draining the lake in entirety. From September through November a tractor pumped countless gallons of water into a nearby drainage ditch, eventually reducing the ten-acre lake to 60 or so feet of sludge.

Still nothing.

In late November, after a bout of appendicitis, Harris threw in the proverbial towel.

“[W]hen I came out of the hospital I said, That was it,” Harris reflected during a 1971 interview. “… when I laid up there on the verge of death, that’s when I made up my mind that this thing was gonna stop.”

The hunt did stop, though Oscar’s legacy lives on.

Since 1950, Churubusco has held its annual Turtle Days festival—a two-day extravaganza complete with barbershop quartets, a pie-eating contest, and more than a few cartoonish images of the town’s default mascot. These days Oscar is everywhere: on welcome signs and window fronts and a larger-than-life statue at the entrance of the community park.

But despite the kitsch, I’m still after the real Oscar, or at least proof of his having been there. Yet as the Chucks inform me, few artifacts from that era remain.

“We got one of the spotlights used during the hunt,” Chuck Jones says, pulling an enormous light from a case. “We plugged it in for about one second, and it … is … bright.”

“And then there’s the net they used to try to capture him with …” Chuck Matheiu adds.

“Net?” I ask, my interest piqued. “Where’s the net these days?”

“Well, last I heard it was in the basement of the funeral home.”

Though I have a hard time believing a 300-foot net has been stored in a funeral home, I call up Churubusco’s nonetheless. Funeral home employee Miles Wilson is equally skeptical, though when I inform him that the Chucks have offered me this hot tip, he agrees to have a look. Initially, he finds nothing, though in an attempt to offer something he off-handedly mentions he’s the great-grandson of Charlie Wilson, one of the two men who first spotted Oscar while fishing in July of ‘48.

“You’re kidding,” I laugh. “It’s like everyone in town has some connection.”

“They do,” he says.

Miles promises to keep looking and asks me to call back later that afternoon. When I do, he surprises me by confirming there is indeed a net tucked into a horse trough in the bowels of the funeral home.

“Is it accessible?” I ask. “I mean could one hypothetically get to it if one tried?”

“Tell you what,” Miles says, cutting through the “hypothetical” business, “if you make the trip we’ll make it happen.”

I hang up the phone, but I don’t make the trip. What’s the point? I wonder. If Harris and his net couldn’t capture the turtle, how could I capture the truth?

Photos courtesy of the Churubusco History Center.