Having written recently about the “danger of narrative”—how stories can distract us from thinking critically to make harmfully distorted representations seem natural and true—I thought it insufficient, if not irresponsible, not to make room for that other equally important possibility: narrative’s positive power.

In her well-known TED Talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie argues for the importance of a multiplicity of stories, voices, and perspectives in order to do justice to the fullest range of experience and explode reductive stereotypes of people and places. “Stories matter,” she says. “Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and malign. But stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity.”

As individual writers contributing our own stories to this multiplicity we might ask ourselves which stories, of the ones we can tell, need to be told. But no matter which stories we end up telling, we must attend to the ways craft itself can create opportunities for constructive and responsible representation. Many misrepresentations, for example, speak to lazy characterization. Characters, after all, are people as far as we’re concerned, and so we must work to ensure our characters, our people, have the richness and complexity readers require in order to care about, inhabit, and empathize with them. I’ve always found inspiration in the way Tobias Wolff puts it in his Paris Review interview:

And the most radical political writing of all is that which makes you aware of the reality of another human being. Self-absorbed as we are, self-imprisoned even, we don’t feel that often enough. Most of the spiritualities we’ve evolved are designed to deliver us from that lockup, and art is another way out. Good stories slip past our defenses—we all want to know what happens next—and then slow time down, and compel our interest and belief in other lives than our own, so that we feel ourselves in another presence. It’s a kind of awakening, a deliverance, it cracks our shell and opens us up to the truth and singularity of others—to their very being. Writers who can make others, even our enemies, real to us have achieved a profound political end, whether or not they would call it that.

Note how Wolff suggests that what can make narrative dangerous—its ability to “slip past our defenses”—is the very same thing that can make it positively powerful. Instead of blunting our critical faculties, stories can disarm us of our misconceptions, biases, and fears.

*

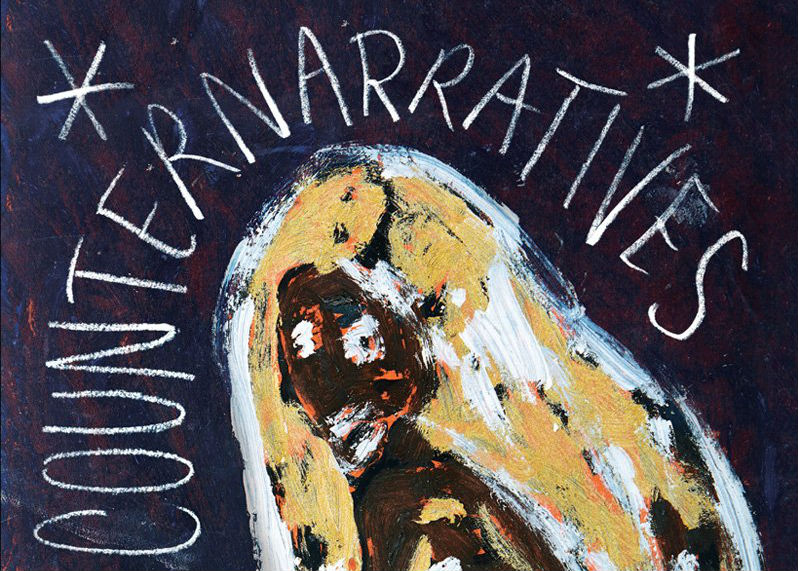

What about writers and stories who keep us both thinking critically and, at the same time or by turns, drawn in empathetically? Consider John Keene’s recent and deeply rewarding collection out from New Directions, Counternarratives.

The book’s title already asserts the power of some stories to push back, challenge, or yes, counter the harm done by other stories. Keene’s “Counternarratives” (and “Encounternarratives,” accounting for about half of the collection) themselves are often about competing, stratified orders—Portuguese and Dutch imperialists, indigenous inhabitants of the “new world,” slaves abducted from Africa, to draw only a few examples from the beginning of the book, which proceeds chronologically—and are set during times of political and personal upheaval. But rather than simply retell the history of the Americas that has already been handed to us by our school books, in a feat of defamiliarization Keene’s work strives to offer us new perspectives, new versions, new voices. Not only new, but needed: these stories help restore agency, depth, and dignity to figures formerly denied full representation—Jim from Huckleberry Finn (“Rivers”), say, or the acrobat silent and frozen in Edgar Degas’s famous painting (“Acrobatique”)—as well as to the anonymous victims of white systems of oppression and control.

The book’s title already asserts the power of some stories to push back, challenge, or yes, counter the harm done by other stories. Keene’s “Counternarratives” (and “Encounternarratives,” accounting for about half of the collection) themselves are often about competing, stratified orders—Portuguese and Dutch imperialists, indigenous inhabitants of the “new world,” slaves abducted from Africa, to draw only a few examples from the beginning of the book, which proceeds chronologically—and are set during times of political and personal upheaval. But rather than simply retell the history of the Americas that has already been handed to us by our school books, in a feat of defamiliarization Keene’s work strives to offer us new perspectives, new versions, new voices. Not only new, but needed: these stories help restore agency, depth, and dignity to figures formerly denied full representation—Jim from Huckleberry Finn (“Rivers”), say, or the acrobat silent and frozen in Edgar Degas’s famous painting (“Acrobatique”)—as well as to the anonymous victims of white systems of oppression and control.

In “An Outtake from the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution,” for example, we follow the sinuous trajectory of the life of Zion, a chronically escaping slave in Boston at the dawn of the American Revolution. To call Zion’s story “An Outtake” is to draw attention to the “counter” stance of this narrative against the received narrative of our history (the title also references a Pulitzer prize-winning history book)—it’s the aspect of the story edited out, suppressed, silenced. But returning agency to Zion by telling his story isn’t quite enough for Keene; the story he tells also serves to disrupt the comforting and simplifying assumptions we might be tempted to make about a character like this. To represent any character, even one who has been historically mis- or underrepresented, as perfect or infallible is to deny that character full complex humanity. So in “An Outtake,” Keene allows Zion’s relationship to our sympathies to be just as slippery as his relationship to his owners—just as they literally cannot hold him in place, we cannot force him to be simply either good or bad. In one paragraph we admire his cunning and determination:

… Zion charmed a Dutch whore strolling by to untie his bindings, whereupon he set off to find the first loosely hitched horse. As he ran he proclaimed himself free. Under duress one’s actions assume a dream-like clarity. An unattended nag stood outside a tavern, and off Zion strode.

And in the next we recoil at his depravity:

After a spree which stretched from the city of Boston west to the edges of Middlesex County, the slave played his worst hand when he committed lascivious acts just across the county line on the person of a sleeping widow, Mary Shaftesbone, near Shrewsbury. Having broken into her home and reportedly taken violent liberties with her, unaccountably Zion did not flee the town, but entered a nearby tavern and began a round of popular songs, to the delight of the crowd and the horror of the violated woman.

For each different counternarrative, Keene pushes himself to find a form appropriate to his subject. While these formal experiments are part of the joy of the book—“What can he do next?”—they also help highlight the themes basic both to this specific project and, at the end of the day, to all fiction and storytelling.

In “On Brazil, or Dénouement: The Londônias-Figueiras,” we start with the image of a recent newspaper staff report on a corpse found in a São Paulo favela. From here Keene travels back to the early fifteenth-century to bring us slowly back to the found corpse, demonstrating how an awareness of the past can deepen our understanding of the present and suggesting the shortcomings of the officially sanctioned narrative (the newspaper text). In “A Letter on the Trials of the Counterreformation in New Lisbon,” the story of a priest sent to reform the wayward House of the Second Order of the Discalced Brothers of the Holy Ghost takes on increasingly charged meaning as we realize who, unexpectedly, is telling the story (that is, writing the letter).

Perhaps my favorite of Keene’s counternarratives is “Gloss on a History of Roman Catholics in the Early American Republic, 1790-1825; or the Strange History of Our Lady of the Sorrows.” Like “On Brazil” or “A Letter,” this novella draws our attention to the fact of its written-ness in a way that prompts us to think about who gets to tell what story, who is granted voice.

Formally, “Gloss” is an eighty-page footnote. An “outtake” of sorts, just as we’re acclimating to the dry, dense terrain of the title’s first “History,” in a subversive inversion the footnote interrupts and takes over to tell the story of Carmel, “the lone child among the handful of bondspeople” remaining on a Haitian coffee plantation in 1803. Carmel’s story carries her from Haiti to a convent in Kentucky, where she serves a demanding white teenage girl. At first Carmel is mute—a silenced voice, perhaps, someone marginalized to the point of near invisibility or at least inhumanity: “Up until this point [her owner] had not really noted her presence, considering her no more extensively than one might remember an extra utensil in a large hand-me-down table service.” Instead of communicating verbally, Carmel draws; her drawings, as well as her silence, are subject to unfair projection and interpretation by other people, though she herself, like many writers, doesn’t fully understand what she creates.

As “Gloss” goes on to cover a series of strange and harrowing events at the Kentucky convent, Carmel gradually gains agency; as she gains agency, her voice takes over the narration, first as a series of diary entries in a kind of pidgin shorthand, then as a more straightforward first-person narrative in Standard English. Towards the end of the novella, she even takes on supernatural powers of the kind projected onto her earlier mysterious silence. Like a writer manipulating his characters, Carmel brings what I think we could justify calling her Künstlerroman to a climax by employing her newly developed ability to physically move people through space, compelling them to do what she wants with her mind—all from a place, again authorial, of literal self-willed invisibility. At the end of “Gloss” we see Carmel retelling her story to a group of fellow escaped servants.

In this way Keene’s Counternarratives both demonstrate and enact the power of narrative. They not only use important stories to assert the dignity of misrepresented characters and invite our empathy, but they also ask us to think critically about how stories wield their power.